August 1831 changed everything in the American South. Before the blood started spilling in Southampton County, Virginia, there was a feeling. A vibe, almost. People knew something was brewing. You’ve probably heard the basic version in high school history—a guy named Nat Turner led a bunch of enslaved people on a rampage, it was put down, and then things got worse. But that's just the surface. Honestly, the reality of Nat Turner's slave rebellion is way grittier, more calculated, and frankly more terrifying for the people living through it than most textbooks let on.

It wasn’t just a random outburst of anger. Not even close.

Turner was an intelligent, literate man. In an era where teaching an enslaved person to read was seen as a threat to the entire economic engine of the South, Turner was deep into the Bible. He was a preacher. People looked up to him. He saw visions. He thought the sky turning a weird greenish-blue color was a literal sign from God to start the work of "slaying his enemies with their own weapons."

The Solar Eclipse and the Signal to Strike

It started with the sun. On February 12, 1831, there was a solar eclipse. Turner saw this as the "black man's hand" covering the sun. He didn't just rush out into the streets, though. He waited. He recruited four close friends: Henry, Hark, Nelson, and Sam. They were cautious. They were quiet.

Then came August 13. The atmosphere looked strange again. A second atmospheric phenomenon—likely just some high-altitude dust—made the sun appear bluish-green. That was it. That was the green light. On the night of August 21, they met in the woods, ate some dinner (pig and cider, if you want the specifics), and started the march.

They began at the home of Joseph Travis. He was Turner's owner at the time. They killed the entire family while they slept. It’s brutal to think about, but for Turner, this wasn't about personal grudges. It was about dismantling a system. They moved from house to house. They didn't use guns at first because they didn't want to alert the neighbors. They used axes. They used hatchets. Basically, anything that could kill quietly.

Why Nat Turner's Slave Rebellion Was Different

Most slave revolts before this—like Gabriel Prosser’s in 1800 or Denmark Vesey’s in 1822—were snitched on before they even started. Someone always got cold feet. Someone always talked. Nat Turner's slave rebellion actually happened. That’s why it’s the most famous one. It wasn't just a plan; it was an execution.

By the next morning, Turner’s group had grown to about 50 or 60 men. Some were joined by choice; others were basically pressed into service as the group swept through plantations. They were heading for Jerusalem, the county seat. They wanted the armory. If they got the guns, the rebellion could have spread across the entire state.

But they never made it.

White militias organized fast. It was chaos. There was a skirmish at Parker’s Old Field. The rebels scattered. Some were captured, some were killed on the spot, and some—like Turner—just vanished into the woods.

The Aftermath and the Great Fear

What happened after the rebellion is arguably more important for American history than the revolt itself. The panic was infectious. It spread like a virus across the South. White Southerners weren't just scared of Turner; they were scared of the guy serving them dinner. They were scared of the person picking their cotton.

The retaliation was mindless. State militias and random mobs didn't just go after the rebels. They killed nearly 200 Black people, many of whom had absolutely nothing to do with Turner. They were just in the wrong place at the wrong time.

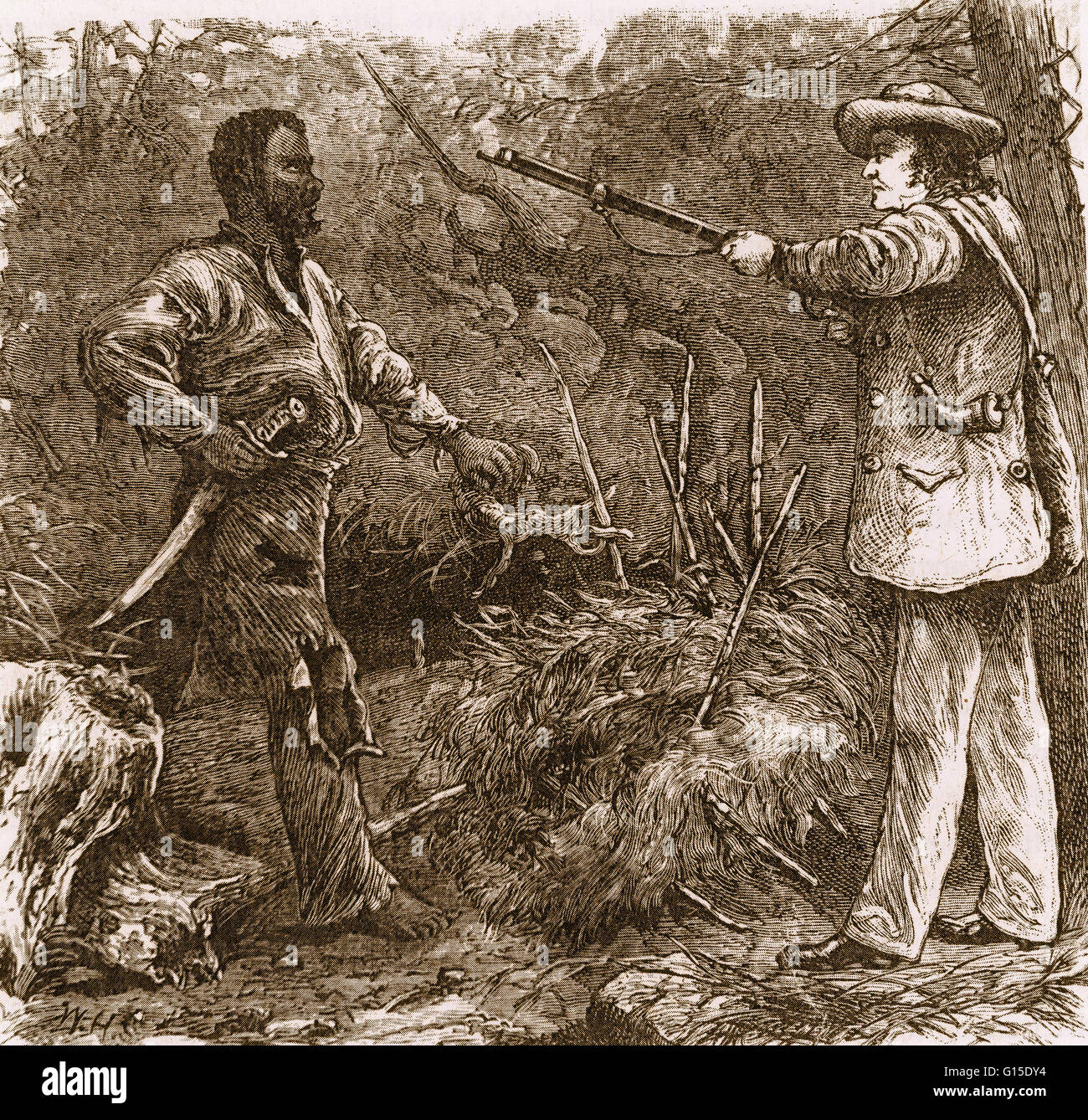

Turner himself stayed hidden in a "light hole" (a hole in the ground covered with branches) for six weeks. Six weeks! Right under their noses. He was finally caught by a local farmer named Benjamin Phipps on October 30. He didn't fight back. He just gave up.

The Confessions of Nat Turner: Truth or Propaganda?

While he was in jail waiting to be hanged, a lawyer named Thomas Ruffin Gray interviewed him. This became "The Confessions of Nat Turner."

👉 See also: East Coast Earthquake Fault Lines: Why They Are So Much Scarier Than San Andreas

Now, you have to be careful with this document. Is it Nat Turner’s actual voice? Sorta. Gray definitely had an agenda. He wanted to make Turner look like a religious fanatic—a "gloomy fanatic" as he called him—to prove that "normal" enslaved people were happy and only someone "crazy" would revolt. But even through Gray’s bias, you can feel Turner’s conviction. When asked if he regretted what he did, Turner’s response was chillingly simple: "Was not Christ crucified?"

The Legal Crackdown: Killing the Mind

Before 1831, there was a tiny bit of wiggle room in the South. Some enslaved people could learn to read. Some could gather for church without a white person watching them. After Nat Turner's slave rebellion, that window slammed shut.

Virginia and other Southern states passed "Black Codes." They made it illegal to teach any Black person, free or enslaved, to read or write. They banned Black people from holding religious meetings without a white licensed minister present. They restricted the movement of free Black people. Basically, they tried to lobotomize the intellectual life of the Black community to prevent another Nat Turner from rising.

It backfired, though. In the North, the rebellion gave the abolitionist movement a massive jolt. William Lloyd Garrison, who had just started The Liberator, used the event to argue that slavery was a ticking time bomb. He basically said, "If you don't end slavery now, there will be a thousand Nat Turners."

Why We Still Talk About Him Today

History is messy. People want Nat Turner to be a clean-cut hero or a pure villain. He’s neither. He was a man pushed to the absolute brink by a system that treated him like a piece of farm equipment. He used extreme violence, yes. But he was responding to a system of extreme violence.

💡 You might also like: Did Amendment 1 Pass in Florida: What Really Happened

Historians like Stephen B. Oates, who wrote The Fires of Jubilee, point out that Turner was a product of his environment. He was a man who believed he was an instrument of divine justice. Whether you see him as a freedom fighter or a murderer usually depends on which side of the whip you imagine yourself on.

Key Takeaways for Understanding the Impact

- The Psychological Shift: The South moved from seeing slavery as a "necessary evil" to a "positive good" that needed to be defended with militant force.

- The Communication Gap: The crackdown on literacy was a direct response to Turner’s ability to read and interpret the Bible for himself.

- The Path to Civil War: You can draw a direct line from the 1831 rebellion to the hardening of sectional tensions that eventually led to 1861.

What You Should Do Next

If you want to really get into the weeds of this, don't just read the Wikipedia summary. Go to the primary sources.

- Read the original "Confessions of Nat Turner" (1831): But read it with a skeptical eye. Look for where the lawyer Thomas Gray might be putting words in Turner's mouth.

- Visit the sites (if you can): If you’re ever in Virginia, Southampton County still has some of the geography intact. Seeing the swamps where he hid changes your perspective on the sheer endurance it took to survive for those six weeks.

- Check out modern scholarship: Look up the work of Dr. Vanessa Holden. Her book Street Rebellion looks at the role women and children played in the uprising—a group that usually gets ignored in the "lone wolf" narrative of Turner.

- Compare it to other revolts: Look into the 1811 German Coast Uprising in Louisiana. It was actually larger than Turner’s but gets way less press. Understanding why some stories stick and others don't tells you a lot about how we build our national mythology.

The legacy of Nat Turner's slave rebellion isn't just about a few days in 1831. It's about the fear that shaped American laws and the desperate, violent search for freedom that eventually forced a nation to confront its biggest sin. It’s uncomfortable history. But it’s the history that built the world we’re living in now.