Most people think they’ve seen the Moon. They’ve scrolled past that glowing, cratered marble on Instagram or seen a glossy 4K render in a documentary. But honestly, the pictures of the moon from NASA that actually matter aren’t the ones on your phone’s lock screen. They are the grainy, weirdly angled, and sometimes terrifyingly sharp shots buried in the Planetary Data System.

It’s personal for me. I’ve spent hours digging through these archives. The sheer scale of what’s up there—the desolate silence captured in a single frame—is enough to make your skin crawl in the best way possible. We aren't just looking at rocks. We're looking at a record of every bad day the solar system has had for four billion years.

The Evolution of the Lunar Lens

Back in 1966, the Lunar Orbiter 1 sent back the first "high-quality" image of Earth from the Moon’s perspective. It was a smudge. A beautiful, historic, grainy smudge. You have to realize that NASA wasn't just snapping photos for fun; they were scouting parking spots. They needed to know if the Lunar Module would sink into the dust or tip over on a hidden boulder.

Then came the Apollo missions. Hasselblad cameras. These were technical masterpieces. Because there’s no atmosphere to scatter light, the shadows on the Moon are pitch black. There’s no "fill light." If you’re standing in a shadow on the Moon, you’re basically in a void. NASA photographers had to train for months just to handle the exposure settings because the Moon is actually about as dark as fresh asphalt, even though it looks white from your backyard.

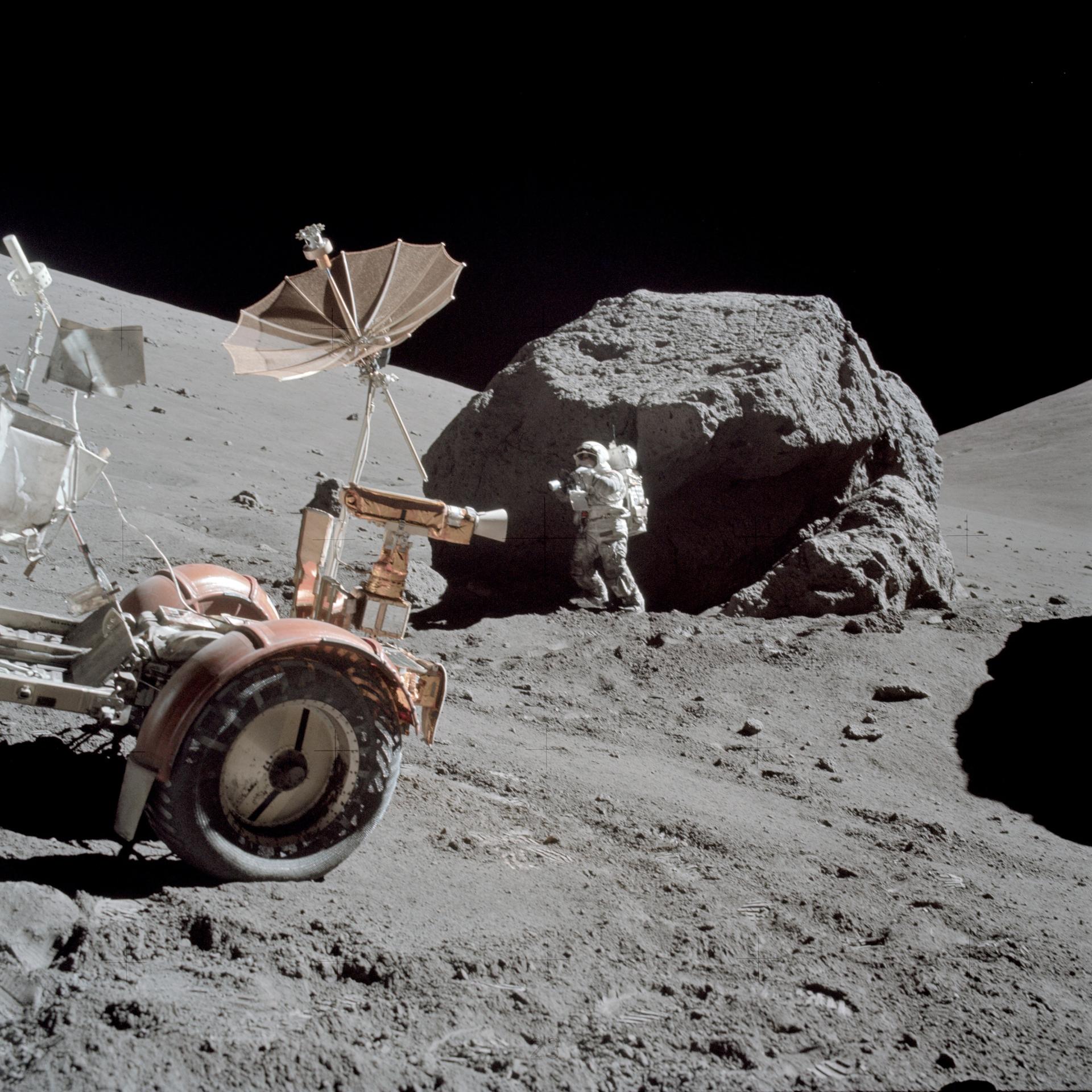

Why Apollo 17 Still Wins

The "Blue Marble" is the one everyone knows, but the surface shots from Apollo 17 are the real deal. Harrison Schmitt, a geologist, was actually on that mission. He knew what to look for. He wasn't just taking "vacation photos." He was documenting the "Orange Soil" at Shorty Crater. When you look at those pictures of the moon from NASA from 1972, you're seeing volcanic glass that cooled millions of years ago. It’s vibrant. It’s weird. It breaks the "grey moon" myth.

The Digital Age: LRO and the New Standard

Right now, there is a satellite called the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) circling the Moon. It’s been there since 2009. It doesn't sleep. It just watches.

🔗 Read more: How I Fooled the Internet in 7 Days: The Reality of Viral Deception

The LRO uses a system called LROC (Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera). This isn't your Nikon. It’s a suite of cameras that can see details as small as a coffee table from 31 miles up. Because of the LRO, we can actually see the descent stages of the Apollo landers. You can see the astronaut footpaths. They look like tiny, dark scratches on the surface. They haven't moved. They won't move for millions of years unless a meteorite hits them.

LRO imagery has changed how we view lunar topography. By using laser altimeters (LOLA), NASA has mapped the Moon’s "peaks of eternal light" and "craters of eternal darkness." At the poles, there are spots where the sun never sets, and others where it hasn't shone for billions of years. We think there’s water ice there. The pictures don't show "ice cubes," but they show the thermal signatures and the reflective shadows that suggest something's hiding in the dark.

The "Fake" Debate and Optical Realities

Let’s address the elephant in the room. People love to say the photos are fake because there are no stars.

Kinda ridiculous, right?

But from a photography standpoint, it makes total sense. If you take a picture of a brightly lit person in a football stadium at night, the black sky behind them isn't going to show stars. The "daytime" side of the Moon is incredibly bright. If NASA had set the exposure to capture the faint light of distant stars, the Moon itself—and the astronauts—would have been a giant, blown-out white blob.

💡 You might also like: How to actually make Genius Bar appointment sessions happen without the headache

Physics doesn't care about your conspiracy theory.

The Artemis Difference

We are entering a new era. The Artemis program isn't using 70mm film. They are using high-definition digital sensors hardened against radiation. Space radiation is no joke; it "fries" pixels. It leaves little white dots on the sensor that look like "snow."

The recent images from the Artemis I mission—the Orion spacecraft swinging around the far side—were breathtaking. We saw the "Earthrise" again, but in 4K. It’s different this time. The colors are deeper. You can see the weather patterns on Earth with terrifying clarity while the moon's jagged, colorless limb frames the shot.

How to Access the Real Stuff

If you want the real pictures of the moon from NASA, stop using Google Images. You’re getting the "greatest hits" there. Go to the source.

NASA’s Photojournal is the gateway. But if you’re a nerd, go to the LROC Quickmap. It’s basically Google Earth but for the Moon. You can zoom in on specific craters like Tycho or Copernicus. You can change the lighting angles to see how the shadows stretch over the mountains. It is a massive, free playground of data.

📖 Related: IG Story No Account: How to View Instagram Stories Privately Without Logging In

Tips for Navigating the Archives:

- Look for "Raw" images. These haven't been color-corrected. They look flat, but they hold the most data.

- Search by Mission. Apollo is for history; LRO is for detail; Artemis is for the future.

- Check the metadata. NASA usually includes the "Sun Angle." This tells you why a crater looks deep or shallow.

What Most People Miss

The most haunting pictures aren't of the rocks. They are of the shadows.

On Earth, the atmosphere scatters light. Shadows are soft. On the Moon, a shadow is a hard line. It’s binary. Light or Dark. Existence or Void. When you look at a NASA photo of the Moon’s North Pole, you’re looking at a place that is -400 degrees Fahrenheit just inches away from a spot that’s boiling.

Your Next Steps to Lunar Mastery

If you're actually interested in these images beyond just a quick glance, here is how you move from a casual viewer to an amateur analyst.

- Visit the LROC QuickMap. Don't just look at the home page. Use the "Layers" tool to toggle "NAC" (Narrow Angle Camera) frames. This lets you see the Moon at a sub-meter resolution.

- Download a "Tiff" file. JPEGs are compressed and lose detail. If you want to see what the Moon actually looks like, find a high-resolution TIFF file from the NASA archives and zoom in. You’ll see the texture of the regolith—the "moon dust" that’s as sharp as shards of glass.

- Track the Artemis II mission updates. Since this will be the first crewed mission back to the lunar vicinity in over 50 years, the camera tech will be unlike anything we've seen. Watch for the "Live" feeds that NASA TV often tests.

- Learn the difference between "True Color" and "False Color." NASA often uses false color to show mineral composition (like titanium or iron). If the Moon looks like a tie-dye shirt in a photo, it’s not because NASA is lying—it’s because they’re showing you what the rocks are made of.

The Moon is a graveyard of giants and a playground for the next generation. Start looking at the pictures like a map, not a postcard.