Ever looked at one of those vibrant, purple-and-gold NASA images of the Milky Way and thought, "Wait, is that actually what space looks like?" It's a fair question. Honestly, if you were floating out past Pluto, your eyes wouldn't see those neon clouds or those piercing, crystalline pinpricks of light. Space is dark. Like, really dark. But that doesn't mean NASA is faking the data or "photoshopping" the universe to look pretty for Instagram.

What we're seeing is a translation.

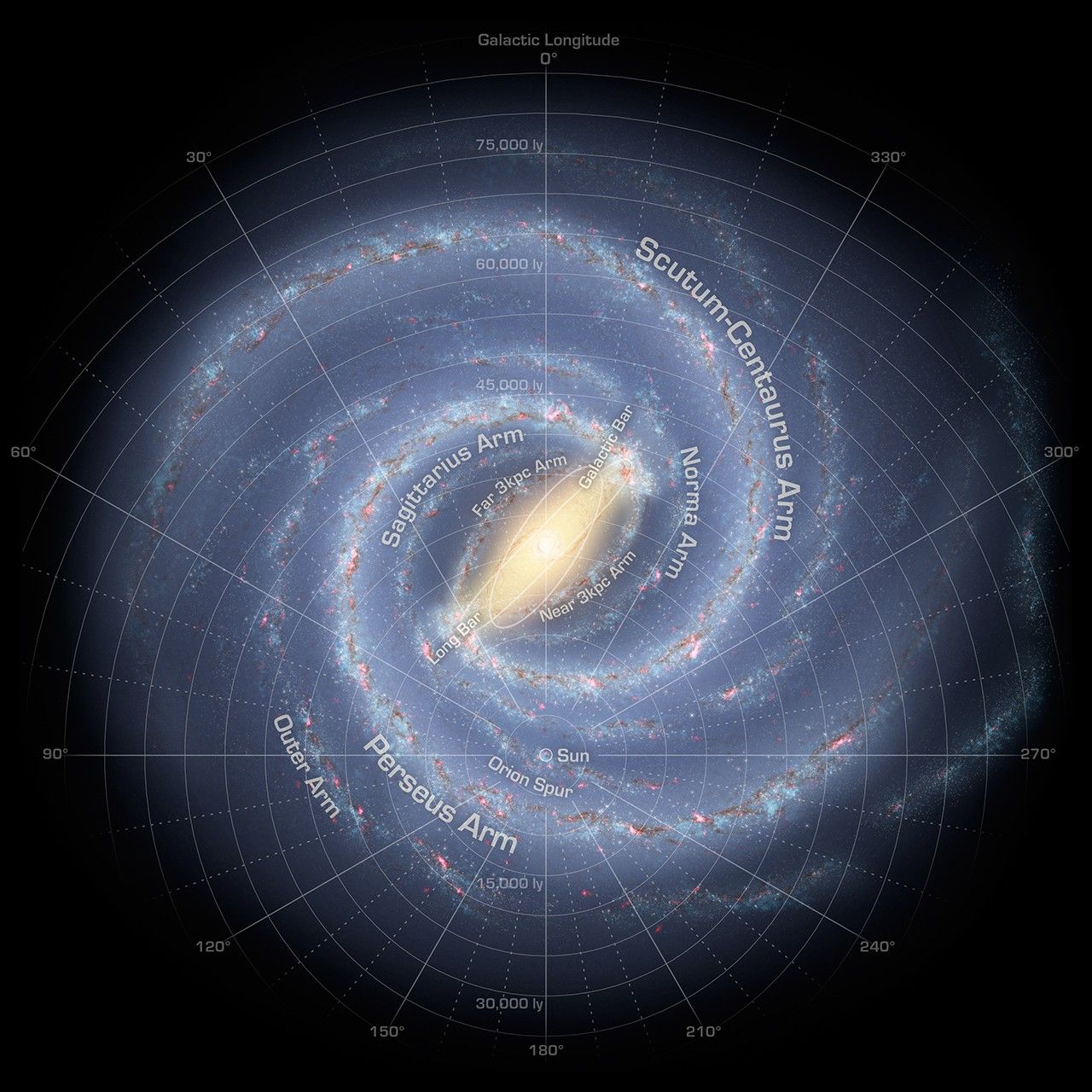

The Milky Way is our home, a massive barred spiral galaxy containing somewhere between 100 to 400 billion stars. Because we live inside it—about 26,000 light-years from the center—capturing its portrait is like trying to photograph the outside of a house while you're locked in the pantry. NASA uses a fleet of "eyes" to do this, ranging from the legendary Hubble to the newer James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), and the results are often mind-bendingly complex once you peel back the layers of how they're made.

The Invisible Galaxy: Why We Can't Just "Take a Photo"

Most people assume a telescope works like a giant Canon DSLR. Point, click, download. But the Milky Way is thick with interstellar dust. This stuff is a nightmare for visible light telescopes. It acts like a thick fog, scattering light and hiding the galactic center from our view. If you only used visible light to capture NASA images of the Milky Way, you’d see a lot of black voids where the most interesting stuff is actually happening.

To get around this, NASA employs "multi-wavelength" astronomy.

They use infrared, X-ray, and even radio waves. Infrared light, for instance, has a longer wavelength than visible light, allowing it to slip past dust particles. This is why the Spitzer Space Telescope was so revolutionary—it could see the "bones" of our galaxy that were previously invisible. When you look at an image of the Milky Way's core, you’re often seeing a composite of several different types of light.

- Visible light: Shows us the stars that look "normal" to our eyes.

- Infrared: Reveals the heat from newborn stars tucked inside gas clouds.

- X-ray: Highlights the "high-energy" drama, like the areas around our central black hole, Sagittarius A*.

NASA scientists, like Dr. Kimberly Arcand, who specializes in data visualization, explain that they assign colors to these different energies. High-energy X-rays might be colored blue, while lower-energy infrared gets assigned red. It’s not "fake." It’s a map. It’s a way to make the invisible data points something our human brains can actually process.

💡 You might also like: Starliner and Beyond: What Really Happens When Astronauts Get Trapped in Space

The Great Galactic Center Mosaic

One of the most famous NASA images of the Milky Way isn't actually one image. It’s a massive mosaic released back in 2009 to celebrate the International Year of Astronomy. NASA combined data from Hubble, Spitzer, and the Chandra X-ray Observatory. It was a beast of a project.

The resulting image shows the chaotic heart of our galaxy. You can see plumes of gas being blown away by massive stars and the glowing remnants of supernovae. Chandra caught the high-energy X-ray glow of gas heated to millions of degrees, while Spitzer caught the cooler dust. When you layer them, you get a full story of the life and death of stars. Without that cross-agency collaboration, we'd only have a fraction of the picture.

The center of our galaxy is a crowded, violent place. It’s nothing like the quiet suburbs where our Sun lives. There are stars there that are so tightly packed they’re practically rubbing shoulders.

Webb Changed the Game

Then came the James Webb Space Telescope.

Webb is basically a time machine. Because it’s so sensitive to infrared light, it can peer through dust with a clarity that Spitzer could only dream of. One of the most striking things Webb has given us is a look at "The Brick." This is a dark, dense cloud of gas near the galactic center where stars should be forming, but for some reason, they aren't.

When Webb took NASA images of the Milky Way's interior regions, it revealed a "needle in a haystack" level of detail. It showed carbon-based molecules floating in the void. It showed the turbulence of the gas. Honestly, the sheer amount of data Webb sends back is so large that it takes months for researchers to "clean" the images, removing the artifacts from the telescope itself so we can see the universe clearly.

📖 Related: 1 light year in days: Why our cosmic yardstick is so weirdly massive

Why the Colors Matter More Than You Think

You might hear critics say, "NASA just paints these things." That’s a bit of a stretch. The color choices are deeply functional.

Imagine you're looking at a heat map of a house. Red is hot, blue is cold. Is the house "actually" red and blue? No. But the colors tell you where the furnace is. NASA images are the same. In many NASA images of the Milky Way, blue often represents the hottest, most energetic phenomena—like the gas being sucked into a black hole. Red and orange usually represent the cooler, older dust.

If we didn't have these colors, the images would just be grayscale blobs of data. We'd lose the ability to distinguish between a dying star and a birthing nebula.

The "All-Sky" Perspective

We also have to talk about the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE). While Hubble and Webb are like "zoom lenses" focusing on tiny patches of the sky, WISE was more of a "wide-angle" lens. It mapped the entire sky in infrared.

When you look at the WISE "All-Sky" map, the Milky Way looks like a bright, glowing ribbon of fire stretching across the screen. It’s a perspective we can't get from the ground because the Earth’s atmosphere blocks most infrared light. Space-based telescopes are the only way we can see the full architecture of the spiral arms we call home.

How to Find the Real Files (Not the Wallpapers)

If you want to see what the scientists see, you shouldn't just look at the JPEG wallpapers on the NASA homepage. You have to go deeper.

👉 See also: MP4 to MOV: Why Your Mac Still Craves This Format Change

NASA maintains the Astrophysics Data System and various "Image Archives" where you can download the raw FITS files. These aren't pretty. They are essentially spreadsheets of light values. But for the nerds among us, these are the real "images." You can use free software like FITS Liberator to try your hand at processing the data yourself.

It's a humbling process. You realize just how much noise is in the vacuum of space. You see the cosmic rays that hit the sensors like little white streaks of "snow." Cleaning those up to create the iconic NASA images of the Milky Way we see in textbooks is a labor of love that combines hard math with artistic intuition.

Don't Forget the "Great Observatories"

Before Webb, we had the four "Great Observatories."

- Hubble (Visible/UV)

- Compton (Gamma rays)

- Chandra (X-rays)

- Spitzer (Infrared)

Most of the "classic" Milky Way photos you've seen in the last twenty years were birthed from this quartet. They were designed to work together. When a supernova went off, NASA would point all of them at the same spot. It was like having a team of specialists—one checking the pulse, one taking an X-ray, one doing a blood test. This holistic approach is why we know the Milky Way is warped. It's not a flat disc; it's actually kinda "floppy" at the edges, like a vinyl record left in a hot car.

Actionable Steps for Exploring the Galaxy

If you're tired of just looking at the same three photos, here’s how to actually dive into the real stuff:

- Visit the NASA Photojournal: This is the "raw" feed. Search for "Milky Way" and filter by "Original" to see the images before they get the PR polish.

- Use WorldWide Telescope: This is a free tool that lets you overlay different NASA images of the Milky Way from different telescopes. You can fade between infrared and X-ray views of the same spot in the sky.

- Follow the Chandra X-Ray Center: They often release "sonifications" of Milky Way images. They turn the light data into sound. It’s haunting, but it gives you a whole new way to "see" the galactic center.

- Check the "Image of the Day" Archive: NASA’s APOD (Astronomy Picture of the Day) is curated by professional astronomers (Robert Nemiroff and Jerry Bonnell). They provide a deep-dive explanation for every single image they post, which helps you avoid the "pretty picture" trap.

The Milky Way is a living, breathing system. Stars are being born in the Orion Nebula right now, and others are exploding in the far reaches of the Scutum-Centaurus arm. These images aren't just art; they’re our only way to see the past and the future of our cosmic neighborhood.

Next Steps for Your Search: To see the latest discoveries, specifically look for the JWST Sagittarius C release. This image shows a star-forming region in the galactic center with unprecedented detail, revealing "needles" of ionized hydrogen that scientists still can't fully explain. Comparing this to older Spitzer images is the best way to understand how far our technology has come in just a decade.