If you look at a map of the United States, Rhode Island is that tiny little speck between Connecticut and Massachusetts that looks like a rounding error. But then you zoom in. You see this massive, jagged tooth taken out of the coastline. That’s Narragansett Bay. It’s basically the heart of the state. Honestly, without the bay, Rhode Island wouldn’t just be smaller; it would be unrecognizable. It's the reason the "Ocean State" isn't just a marketing slogan dreamt up by a board of tourism directors.

People think they know the bay. They think of Newport mansions or maybe a ferry ride to Block Island. But Narragansett Bay Rhode Island is way more complicated than a postcard of a sailboat. It’s 147 square miles of salt water that acts like a massive lung for the region. It’s deep. It’s shallow. It’s incredibly salty in some spots and practically fresh water where the Blackstone River dumps into the Providence River.

The bay is weirdly central to American history, too. We’re talking about the Gaspee Affair in 1772—where local colonists got sick of a British schooner harassing them, lured it onto a sandbar near Warwick, and burned the thing to the waterline. That was a year before the Boston Tea Party. Narragansett Bay was doing revolution before it was cool.

The Three Main Channels (And Which One You Actually Want)

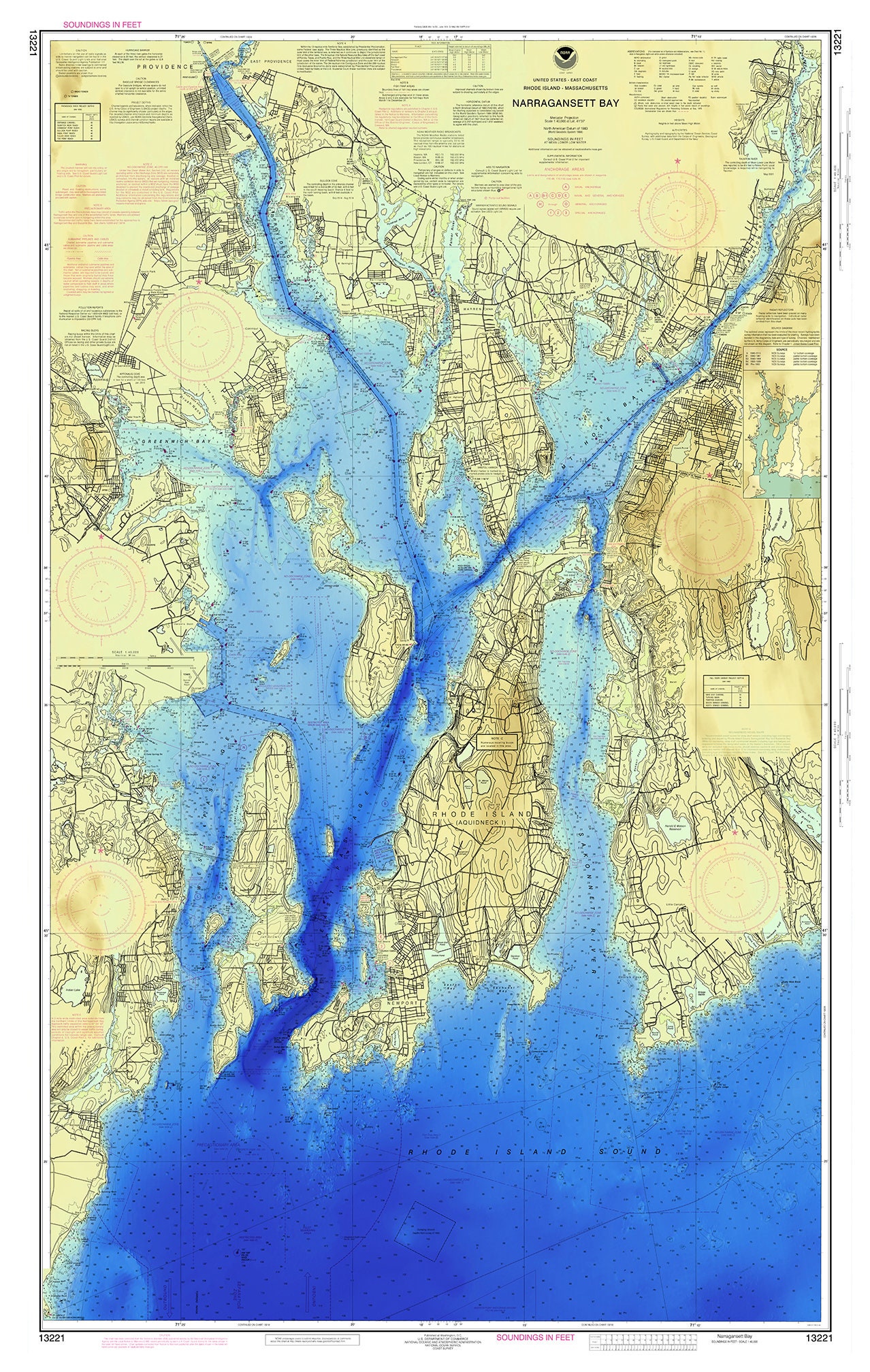

The bay isn't just one big bowl of water. It’s split into three main passages by several large islands. You’ve got the West Passage, the East Passage, and the Sakonnet River. If you’re on a boat, these distinctions are basically your entire life.

The East Passage is the deep one. This is where the big boys play—tankers, Navy ships, and those massive yachts that make you question your career choices. It runs right past Newport. If you want the "classic" experience, this is it. You've got the Pell Bridge arching overhead, which, by the way, is the longest suspension bridge in New England. Driving over it is a rite of passage, but sailing under it? That’s the real view.

Then there’s the West Passage. It’s a bit quieter. More local. You’ll find more fishermen out here and fewer tourists. It separates the mainland from Conanicut Island (where Jamestown is). It’s rugged.

The Sakonnet River is technically a tidal strait, not a river. It’s on the far eastern side, separating Aquidneck Island from Tiverton and Little Compton. It’s skinny, tricky to navigate in spots, but offers some of the most pristine, untouched coastal views in the northeast.

Narragansett Bay Rhode Island: The Fight for Clean Water

You can't talk about the bay without talking about the mess we made of it. For over a century, the bay was basically a toilet for the Industrial Revolution. Providence was a manufacturing powerhouse, which was great for the economy but terrible for the quahogs. Heavy metals, raw sewage, chemicals—you name it, it went into the water.

💡 You might also like: Redondo Beach California Directions: How to Actually Get There Without Losing Your Mind

But things changed. Organizations like Save The Bay (founded in 1970) started screaming about the state of the water. Since then, the turnaround has been nothing short of miraculous.

According to reports from the Narragansett Bay Estuary Program, nitrogen levels have dropped significantly over the last two decades. Why does that matter? Because too much nitrogen causes algae blooms that suck all the oxygen out of the water, killing off fish. Today, you can actually see the bottom in places that used to be murky sludge. It’s not perfect. Stormwater runoff is still a massive headache. Every time it rains heavily, the old combined sewer overflows in Providence can get overwhelmed, forcing beach closures. It’s a work in progress.

The Quahog Economy

If you live here, you don't call them clams. They’re quahogs. Specifically Mercenaria mercenaria.

The bay is a factory for these things. It's a massive industry. You'll see the "bullrakers" out there in their small boats, leaning over the side with long poles, scraping the bottom of the bay. It’s back-breaking work. But that’s where your Rhode Island clam chowder (the clear broth kind, not that creamy New England stuff) comes from. Or "stuffies"—large quahog shells stuffed with breading, minced clams, and linguica.

The Islands You Haven't Visited Yet

Everyone knows Newport. Everyone knows Jamestown. But Narragansett Bay is littered with islands that most people just sail past.

Prudence Island is the big one in the middle. It’s mostly a nature reserve. There are no stores. No real "town." If you go there, you bring your own water and your own food. It’s one of the few places left where you can see what the Rhode Island coastline looked like three hundred years ago. It’s accessible only by a small ferry from Bristol.

Then there’s Patience, Hope, and Despair. Those are real island names. Legend says Roger Williams named them. Despair is really just a rock, which feels appropriate.

📖 Related: Red Hook Hudson Valley: Why People Are Actually Moving Here (And What They Miss)

Dutch Island sits in the West Passage. It’s got an abandoned fort (Fort Greble) that’s being swallowed by the woods. It’s creepy and beautiful. People used to sneak onto it to explore the old batteries, though the state prefers you stay on the designated paths for safety.

The Warming Water Problem

We have to get real for a second. The bay is changing, and it's changing fast. Narragansett Bay is one of the fastest-warming bodies of water in the world.

Scientists at the URI Graduate School of Oceanography have been tracking this for decades. Since the 1960s, the average winter water temperature has climbed by about $3^\circ F$ to $4^\circ F$. That sounds like nothing. It’s actually a catastrophe for some species.

Winter flounder used to be the king of the bay. Now? They’re almost gone. They like cold water. As the bay warms up, southern species are moving in. We’re seeing more black sea bass and even blue crabs—things you used to only find in the Chesapeake. The ecosystem is shifting in real-time. It’s fascinating and terrifying at the same time.

Salt Marshes Are Disappearing

As the sea level rises, the salt marshes—the "nurseries" of the bay—are getting drowned. Normally, a marsh would just migrate inland. But in Rhode Island, we’ve built houses and roads right up to the edge. The marsh has nowhere to go. It gets squeezed. If we lose the marshes, we lose the natural filters that keep the bay clean.

Where to Actually Experience the Bay

If you’re just visiting Narragansett Bay Rhode Island, don't just stay in a hotel. Get on the water.

The Providence-Newport Ferry: This is the best $12 you will ever spend. It takes about an hour. You start in the industrial heart of Providence, weave through the narrow shipping channels, and end up in the middle of Newport Harbor. You see the lighthouses, the mansions, and the massive container ships up close.

👉 See also: Physical Features of the Middle East Map: Why They Define Everything

Colt State Park in Bristol: This is the "people’s park." It’s right on the water. There’s a stone wall that runs for miles along the bay. You can smell the salt air, watch the sunset, and realize why people refuse to leave this state despite the taxes.

Beavertail State Park: Go to the very tip of Jamestown. The waves here crash against the rocks with a violence that’s hypnotic. It’s the entrance to the bay. Looking out from the lighthouse, you realize how small we actually are.

Rome Point: If you want to see seals, go here in the winter. You hike through the woods in North Kingstown to a rocky point. At low tide, the harbor seals haul themselves out onto the rocks to sunbathe. Just don't get too close; they’re cranky.

The Misconception of the "South County" Beaches

A lot of people think the famous beaches like Narragansett Town Beach or Scarborough are "in" the bay. Technically, they aren't. They face the open Atlantic Ocean.

The water inside the bay is generally calmer and warmer. Places like Oakland Beach in Warwick or Fogland Beach in Tiverton are "bay beaches." They don't have the big surf, but they have the character. You're more likely to find families with little kids and people digging for steamers at low tide.

The bay is a working waterway. It’s not just a playground. You have Quonset Point, where they build submarines for the Navy and import thousands of European cars every month. You see the massive wind turbine components being staged for offshore wind farms. It’s a place where industry and ecology are constantly bumping into each other.

The Lighthouses

Narragansett Bay has over a dozen lighthouses still standing. Some are iconic, like Rose Island Light, where you can actually pay to stay the night and play lighthouse keeper. Others, like Conanicut North Light, are just quiet ruins. They are reminders of a time when navigating these waters was a life-or-death gamble every single night.

Actionable Steps for Your Visit

Don't just drive over the bridges. To really "get" Narragansett Bay, you need to engage with it.

- Check the Tide Charts: This is vital. If you’re going beachcombing or looking for seals, the bay looks completely different at high tide versus low tide. Use an app like Saltwater Tides.

- Support the Local Economy: Buy your seafood from a local shack. If the menu says "Point Judith Calamari," get it. That’s the local fleet.

- Take the "Secret" Ferries: Everyone knows the Block Island ferry. Try the Prudence Island ferry from Bristol or the Bristol-to-Prudence-to-Hog-Island run. It’s cheap and gives you a view most tourists never see.

- Visit the Exploration Center: Save The Bay has an exploration center at Easton's Beach in Newport. It’s small but great for understanding exactly what is living under the surface of the water you're looking at.

- Watch the Wind: The bay creates its own weather. A "Sea Breeze" can kick up in the afternoon, dropping the temperature by 15 degrees in ten minutes. Always carry a sweatshirt, even in July.

Narragansett Bay isn't a static landmark. It’s a moving, breathing, sometimes smelly, always beautiful piece of the North Atlantic that defines everything about Rhode Island. It’s survived industrial pollution, hurricane devastation (like the Great New England Hurricane of 1938 that leveled half the coast), and the constant pressure of development. It’s still here. And it’s still the best thing about the smallest state.