Ever tried to rattle off all the names of presidents of the United States in a single go? It’s harder than it looks. Most of us get stuck somewhere around the bearded guys in the late 1800s. You know, the ones who all look like they’re judging your life choices from a dusty daguerreotype.

But honestly, the names themselves tell a weird, winding story of American identity. We’ve gone from "His Excellency" George Washington to a guy everyone just calls "Dubya." It’s not just a list of dead guys. It’s a map of how we’ve changed as a culture.

The Names of Presidents of the United States You’re Probably Misspelling

Let’s get the technical stuff out of the way first. People trip up on the same few names constantly.

Take Millard Fillmore. Why the double 'L' and the double 'O'? It feels like a typo from 1850 that just stuck. Then you've got Dwight D. Eisenhower. Half the internet wants to put an 'n' before the 'h', but it’s Eisen-hower.

And don’t even get me started on the middle initials.

Did you know Harry S. Truman technically didn't have a middle name? The "S" was just an "S." His parents couldn't decide between his grandfathers, Anderson Shipp Truman and Solomon Young, so they just tossed a letter in there to keep the peace. Most style guides say you should put a period after it, but Harry himself often signed it without one.

Pronunciation Pitfalls

- John Quincy Adams: In his neck of the woods (Massachusetts), it’s often pronounced "Quin-zee," not "Quin-see."

- Theodore Roosevelt: He reportedly hated the nickname "Teddy." Also, the family pronounced it "ROZE-a-velt," like the flower, not "RUSE-a-velt."

- Martin Van Buren: He was actually the first president born as a U.S. citizen, but his first language was Dutch. His name was originally Maarten Van Buren.

The Era of the Initials

There was this huge stretch in the 20th century where the names of presidents of the United States basically became acronyms. You’ve got FDR, JFK, and LBJ.

👉 See also: Effingham County Jail Bookings 72 Hours: What Really Happened

It’s kinda fascinating. Before the 1930s, we didn't really do that. You didn't hear people calling Abraham Lincoln "AL" or George Washington "GW." But as mass media took off, those three letters became a brand. They fit in newspaper headlines. They sounded punchy on the radio.

By the time Dwight Eisenhower rolled around, he didn't even need three letters. He just needed three sounds: "I Like Ike."

Honestly, it’s one of the most successful marketing campaigns in history. "Ike" was actually a childhood nickname that stuck. It made a five-star general and Supreme Allied Commander feel like a guy you could grab a beer with at a backyard BBQ.

When Presidents Change Their Names

This is the part that usually surprises people. A few of the men on that famous list weren't actually born with the names we know them by.

Ulysses S. Grant is probably the most famous "clerical error" president. He was born Hiram Ulysses Grant. When he got nominated for West Point, the congressman who submitted his paperwork accidentally wrote "Ulysses S. Grant." Grant tried to fix it, but the bureaucracy was basically like, "Nope, you're U.S. Grant now." He eventually embraced it because the initials stood for "United States" or "Unconditional Surrender."

Then you’ve got Gerald Ford. He was born Leslie Lynch King Jr. His parents split up when he was just an infant, and his mom eventually married a guy named Gerald Rudolff Ford. Young Leslie started going by Gerald Ford Jr., though he didn't officially change it until he was 22.

✨ Don't miss: Joseph Stalin Political Party: What Most People Get Wrong

Bill Clinton has a similar story. He was born William Jefferson Blythe III. His father died in a car accident before he was born, and he eventually took his stepfather's surname when he was a teenager to show solidarity with his half-brother.

The Recent Trend: Numbers and "Dubyas"

Lately, we’ve started using numbers to keep the names of presidents of the United States straight, especially when families get involved.

When George W. Bush took office, we suddenly had a "naming convention" problem. His dad was George H.W. Bush. To differentiate, people started calling the father "41" and the son "43." Or, if you’re from Texas, the son became "Dubya" to emphasize that middle "W."

It’s a weirdly royal vibe for a democracy, isn't it? Having the same name pop up twice in twelve years. We saw it way back with John Adams and John Quincy Adams, but they didn't have 24-hour news cycles to deal with.

The Nicknames That Stuck

Sometimes the nickname is more famous than the actual name.

- Old Hickory: Andrew Jackson. His troops thought he was as tough as a hickory tree.

- The Rail-Splitter: Abraham Lincoln. It was a branding move to make him look like a rugged commoner.

- The Gipper: Ronald Reagan. It came from a movie role he played as George Gipp, a Notre Dame football star.

- Dutch: Also Reagan. His dad thought he looked like a "fat little Dutchman" as a baby.

Actually, the nickname "OK" might even come from a president. Martin Van Buren was from Kinderhook, New York. His supporters formed "Old Kinderhook" clubs, and "OK" became a rallying cry. There’s a bit of debate among linguists about this, but it’s a pretty strong theory.

🔗 Read more: Typhoon Tip and the Largest Hurricane on Record: Why Size Actually Matters

Why Knowing These Names Actually Matters

It’s easy to dismiss this as trivia. But names carry weight. When Barack Hussein Obama was elected, his middle name became a massive point of political contention. It was a name that reflected a globalized, multicultural America, and for some people, that was terrifying. For others, it was the whole point.

Names are our first introduction to a person’s heritage. The shift from the English-inflected names of the Founders (Washington, Jefferson, Madison) to the more diverse roster we see today reflects the changing face of the country itself.

Practical Steps for History Buffs

If you’re trying to memorize the list or just want to sound smarter at your next trivia night, here’s how to actually handle the names:

- Group them by war: It’s much easier to remember James K. Polk if you associate him with the Mexican-American War, or William McKinley with the Spanish-American War.

- Focus on the "Doubles": Remember there are two Adams, two Bushes, two Harrisons, two Roosevelts, and two Johnsons (who both succeeded assassinated presidents).

- The Cleveland Exception: Remember that Grover Cleveland is the only one who counts as two different numbers (22 and 24) because he served non-consecutive terms. This is why Donald Trump is both 45 and 47.

- Check your spellings: Especially for the 19th-century guys. It’s Rutherford B. Hayes, not "Rudford." It’s Zachary Taylor, not "Zachery."

If you’re looking to go deeper, check out the White House Historical Association. They have an incredible archive that breaks down not just the names, but the specific signatures and naming quirks of every single commander-in-chief. You can see how Ulysses S. Grant’s handwriting changed as he got older or how JFK signed his name so fast it almost looked like a straight line.

Ultimately, these names are more than just placeholders in a textbook. They are the brand identities of the American experiment. Whether it’s the "The Sage of Monticello" or just "45," the way we name our leaders says a lot about who we think we are at any given moment in time.

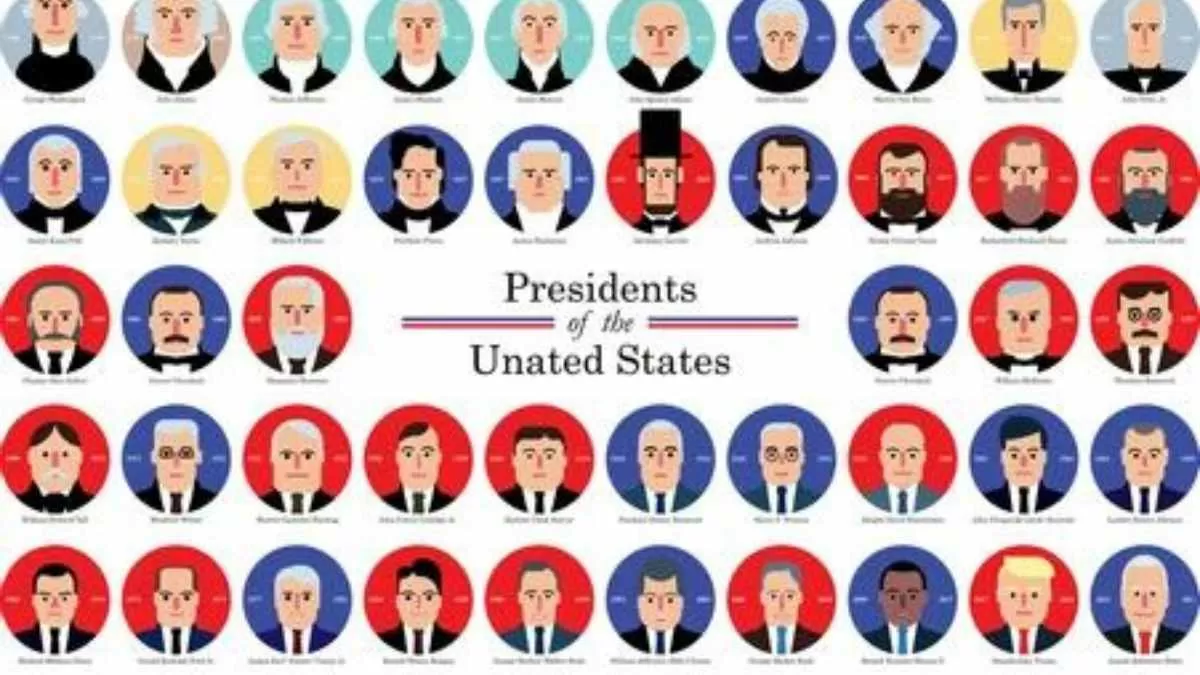

To truly master the history of the executive branch, start by looking at the official presidential portraits alongside their biographies. Seeing the face behind the name helps cement the chronological order in a way a simple list never will. You might even find yourself recognizing Chester A. Arthur by his mutton chops alone.