It is a drizzly night in Covent Garden. You see a woman with a smudge of soot on her cheek, shrieking "Aoooooogah!" at a man who just knocked over her flower basket. That’s her. That’s the My Fair Lady Eliza Doolittle character we all think we know. But honestly? Most people get her completely wrong. They think she’s just a passive doll that Henry Higgins painted a new face on.

She isn't. Not even close.

Eliza is a survivor. She is a street-smart entrepreneur in a world that wants her to stay invisible. When we look at the history of musical theater, Eliza Doolittle stands out because she is one of the few female leads who actually demands a receipt for her soul. She doesn't just want to talk like a duchess; she wants the agency that comes with it.

The Cockney Flower Girl with a Plan

George Bernard Shaw wrote Pygmalion in 1912. He was a socialist, a crank, and a genius. He didn't write Eliza to be a Disney princess. He wrote her to expose the absolute absurdity of the British class system. In the musical adaptation, My Fair Lady, the Lerner and Loewe songs give her a bit more "bloom," but that grit remains.

Think about her first major move. She doesn't wait for Higgins to find her. She shows up at his house. She has a shilling in her hand—which, for her, is a massive amount of money—and she demands lessons. She’s a paying customer. She has a business goal: to work in a flower shop instead of selling on the street corner.

That’s the core of the My Fair Lady Eliza Doolittle character. She is driven by economic mobility. While Higgins treats the whole thing like a laboratory experiment with a "squashed cabbage leaf," Eliza is playing for keeps. She knows that in 1912 London, a woman's voice is her cage or her key.

What Most People Get Wrong About the "Transformation"

We love a makeover montage. We love the "The Rain in Spain" moment where she finally gets the vowels right and they dance around the study. It’s catchy. It’s triumphant. But the real transformation isn't the accent.

It’s the realization that once you change how the world sees you, you can never go back to who you were.

👉 See also: Finding a One Piece Full Set That Actually Fits Your Shelf and Your Budget

Higgins is a brilliant phonetician but a total disaster as a human being. He forgets that Eliza has feelings. He treats her like a pebble. When she finally passes the test at the Embassy Ball, he and Colonel Pickering pat each other on the back like they just won a cricket match. They completely ignore her.

This is where the My Fair Lady Eliza Doolittle character becomes a proto-feminist icon. She throws his slippers at him. She realizes that she has been "filled with manners and habits" that make her unfit for the gutter but don't give her a place in the parlor. She is in a social no-man's-land.

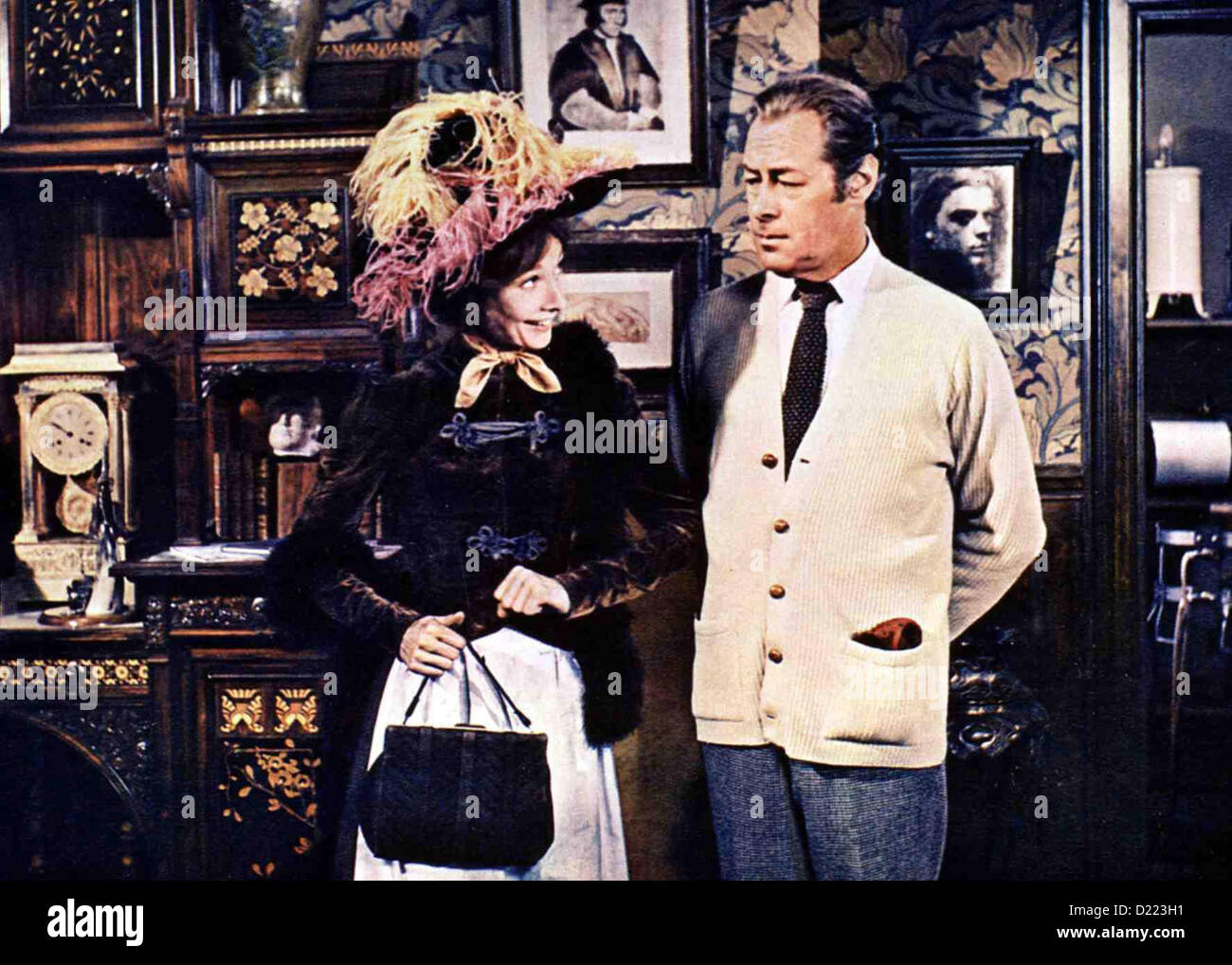

The Audrey Hepburn vs. Julie Andrews Debate

You can't talk about Eliza without talking about the 1964 film. It’s a masterpiece of production design, but it’s also a point of huge controversy.

- Julie Andrews originated the role on Broadway. She was perfection. Her voice was a crystalline instrument that perfectly tracked Eliza’s journey from grit to grace.

- Jack Warner didn't think Andrews was a big enough "star" for the movie. He hired Audrey Hepburn.

- Hepburn was dubbed by Marni Nixon.

Fans still argue about this. Hepburn brings a fragile, deer-like quality to the later scenes that is heartbreaking. But many theater purists feel that Eliza’s strength is lost when you take away the actress's actual singing voice. It creates a disconnect.

Regardless of who plays her—from Wendy Hiller in the 1938 film to Lauren Ambrose in the recent Lincoln Center revival—the character's "spine" remains the same. She is a woman who discovers that "the difference between a lady and a flower girl is not how she behaves, but how she’s treated."

Why the Ending is So Polarizing

Shaw was adamant: Eliza should never end up with Higgins. In his original play and his later "sequel" essay, he insisted she marries Freddy Eynsford-Hill. He thought Higgins was an unrepentant predator and Eliza was too smart to spend her life fetching slippers for a man who didn't respect her.

The musical softens this. It gives us "I've Grown Accustomed to Her Face." It gives us that final, ambiguous moment where she returns to his house and he asks, "Eliza, where the devil are my slippers?"

✨ Don't miss: Evil Kermit: Why We Still Can’t Stop Listening to our Inner Saboteur

Is it a romantic happy ending? Or is it a tragedy where she settles for a life of intellectual servitude?

Modern interpretations lean toward the latter. If you watch the 2018 Broadway revival directed by Bartlett Sher, the ending is tweaked significantly. Eliza doesn't stay. She walks out through the audience, leaving Higgins alone in his dusty museum of phonetics. This version feels much more aligned with the My Fair Lady Eliza Doolittle character as a symbol of independence.

The Social Science of the "Doolittle Effect"

There is actually a psychological concept often linked to this story: the Pygmalion Effect.

Basically, it’s the idea that high expectations lead to improved performance. Higgins expected Eliza to become a duchess, so she did. But the "Galatea" flip side—named after the statue that came to life—is that the creation eventually develops a will of her own.

Eliza’s journey mirrors real-world studies on linguistic bias. Even today, people make snap judgments about intelligence based on regional accents. Whether it's a Cockney lilt or a Southern drawl, the "standard" dialect is used as a gatekeeper for power. Eliza Doolittle is the ultimate "hacker" of this system. She learns the code, uses it to bypass the security, and then realizes the room she broke into is actually quite empty and boring.

Nuance in the Supporting Cast: Alfred P. Doolittle

We can't ignore her father, Alfred. He’s the "undeserving poor." He represents the flip side of Eliza’s journey. While Eliza works tirelessly to move up, Alfred is thrust into the middle class against his will because of a joke Higgins made to an American millionaire.

The My Fair Lady Eliza Doolittle character is defined by her struggle for morality and "middle-class respectability." Her father, meanwhile, mourns the loss of his freedom. He loses his right to be "irresponsible." This contrast shows that class isn't just about money or clothes; it's a set of chains that binds you regardless of which rung of the ladder you're on.

🔗 Read more: Emily Piggford Movies and TV Shows: Why You Recognize That Face

Key Traits of a Compelling Eliza

If you are an actor or a writer studying this role, there are a few non-negotiables:

- The Ear: Eliza is a genius-level mimic. She picks up the most complex phonetics in months. She isn't "uneducated" in terms of brainpower; she’s just unrefined.

- The Pride: Even when she’s covered in dirt, she has a fierce sense of self-worth. "I'm a good girl, I am!" is her mantra.

- The Vulnerability: Underneath the barking "garn!" is a girl who just wants to belong somewhere.

- The Transformation: It must be physical. Her posture, the way she holds her chin, the way she breathes—it all shifts from the diaphragm of a street hustler to the lungs of an aristocrat.

Actionable Insights: Learning from Eliza

What can we actually take away from the My Fair Lady Eliza Doolittle character in 2026?

First, invest in yourself. Eliza took her only savings to Higgins’ door. She saw herself as an asset worth developing. That’s a lesson in self-advocacy that never goes out of style. If you don't value your potential, no one else will.

Second, understand the power of presentation. Like it or not, the way we speak and carry ourselves dictates how doors open. You don't have to lose your identity, but learning "the language of the room" is a tool for survival. Eliza didn't become a different person; she just learned a second language—the language of the elite.

Third, know when to walk away. The most powerful thing Eliza does isn't winning over the Queen of Transylvania. It’s leaving Higgins. She realizes that no amount of status is worth being diminished as a person.

To truly understand Eliza Doolittle, you have to look past the Ascot hats and the white lace dress. Look at the woman who, after being told she was nothing, looked her "creator" in the eye and told him she could do just fine without him. That is the real Eliza. She isn't a project. She’s a powerhouse.

If you want to dive deeper into the history of the role, start by reading the original 1912 script of Pygmalion. Compare it to the 1956 musical libretto. You’ll see how the character has evolved from a social commentary tool into a complex portrait of female autonomy. Pay close attention to her dialogue in Act V—it’s where the "flower girl" finally dies and the woman is born. Check out the 1938 film version starring Wendy Hiller for a take that is much closer to Shaw's original, less-romanticized vision. It changes the way you see the "Happy Ending" forever.