You probably haven’t thought about methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) in a while, but honestly, your car’s engine and your local groundwater definitely have. It’s one of those chemical compounds that seemed like a literal godsend until it wasn't. Back in the late 70s and 80s, the oil industry was in a tight spot. Lead was being phased out of gasoline because it was poisoning everyone, and refiners needed a new way to boost octane levels and help fuel burn cleaner.

Enter MTBE.

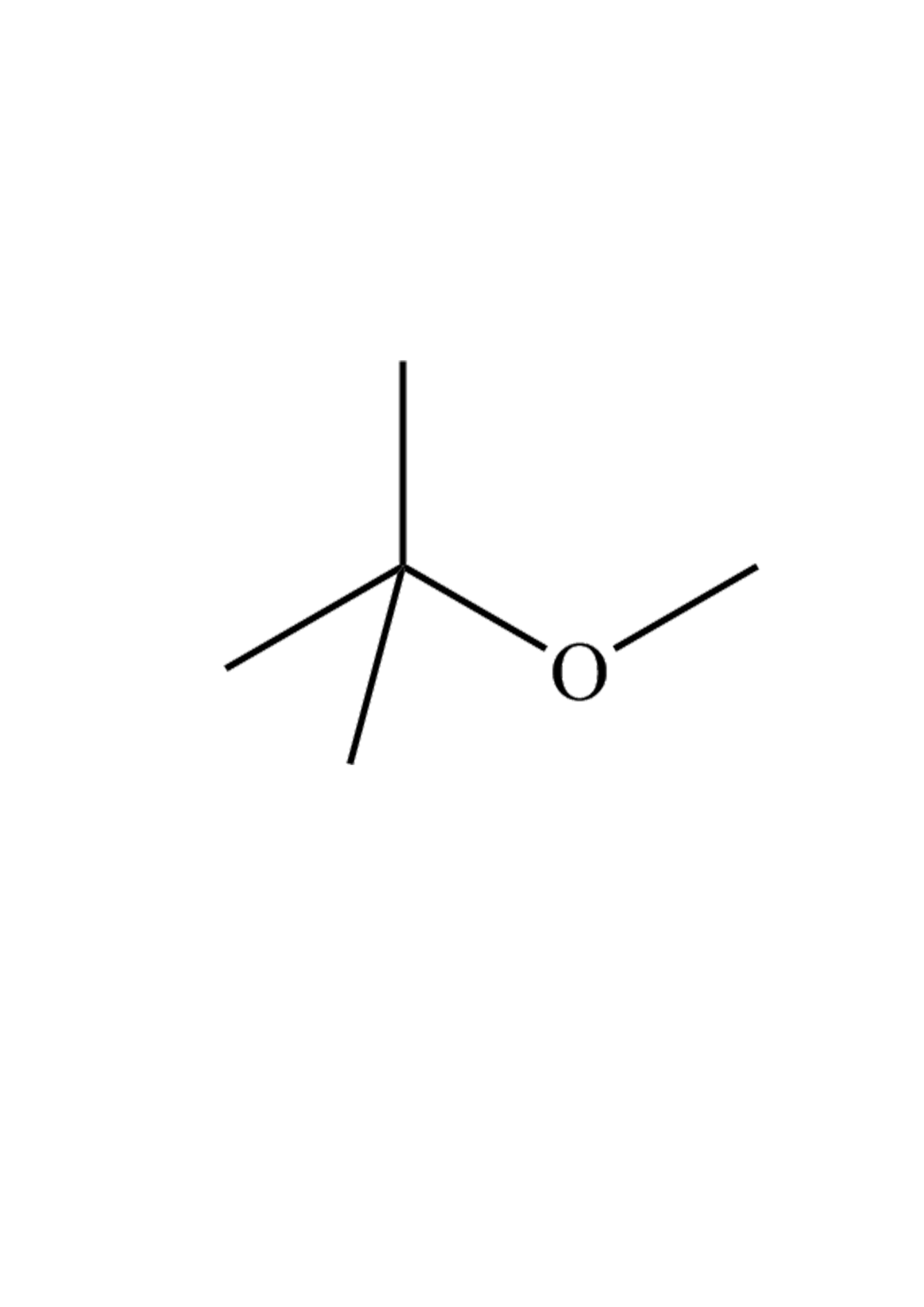

It’s a volatile, flammable, and colorless liquid. It has a kinda funky, terpene-like smell that most people find pretty unpleasant. Chemically, we’re talking about a molecule where a methyl group is joined to a tert-butyl group through an oxygen atom. Basically, it’s an oxygenate. By adding oxygen to the fuel mix, it helps the gasoline burn more completely, which reduces the nasty carbon monoxide and soot coming out of your tailpipe. For a decade or two, it was the golden child of the Clean Air Act.

The Rise and Fall of Methyl Tert-Butyl Ether

The 1990 Clean Air Act amendments basically forced the use of oxygenates in areas with bad smog. Refiners jumped on MTBE because it was cheap to produce from byproducts of the refining process itself. By 1999, it was the second most produced organic chemical in the United States. It worked. Air quality in major cities like Los Angeles and New York actually started to improve.

But there was a massive problem lurking underground.

Unlike most components of gasoline, methyl tert-butyl ether is incredibly soluble in water. If an underground storage tank at a gas station leaked—and let’s be real, thousands of them did—the MTBE wouldn't just sit there. It would hitch a ride on the groundwater and travel faster and farther than any other part of the gasoline plume. It didn't take long for people to start turning on their kitchen faucets and smelling something like turpentine or rotting fruit.

Why It Became a Legal Nightmare

By the early 2000s, the tide had turned. Santa Monica, California, had to shut down a huge chunk of its municipal water supply because of MTBE contamination. We are talking about concentrations as low as 20 parts per billion (ppb) making water totally undrinkable because of the taste and smell. Even if it wasn't necessarily toxic at those levels—the EPA still classifies it as a "potential" human carcinogen—nobody wants to drink "gasoline water."

The lawsuits were massive.

The industry tried to argue that the government forced them to use it. The courts mostly didn't care. Eventually, states started banning it one by one. California led the charge, and by 2005, the federal government removed the oxygenate requirement, effectively killing MTBE's reign in the US domestic fuel market. Most refiners switched to ethanol, which has its own set of problems, but at least it biodegrades much faster in a spill.

Is It Still Around?

You might think it’s gone. It’s not.

While you won't find it in your local pump in the US anymore, methyl tert-butyl ether is still a massive global commodity. It is still used heavily in various parts of Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America. Why? Because it’s an incredibly efficient octane booster. If a country doesn't have a massive corn lobby pushing ethanol, MTBE is often the most economical way to get high-performance fuel.

Beyond fuel, it’s a vital solvent in the lab. If you’re a chemist doing a Grignard reaction, MTBE is often preferred over diethyl ether because it has a higher boiling point and is way less likely to form explosive peroxides. It's safer to store. It’s also used in medicine, specifically for dissolving gallstones. Doctors can actually inject it directly into the gallbladder to dissolve stones without surgery. It's a niche use, but it's a lifesaver for some patients.

The Environmental Persistence Factor

The real headache with MTBE is that it just doesn't like to die. In the environment, it's resistant to "biodegradation." Most soil bacteria look at that tert-butyl structure and don't know what to do with it. It lacks a "handle" for enzymes to grab onto.

- It doesn't stick to soil particles.

- It moves at nearly the same speed as the groundwater itself.

- It stays in the aqueous phase rather than evaporating out easily.

If you are dealing with a contaminated site, you usually have to use advanced oxidation processes—like hitting it with high-dose ozone and hydrogen peroxide—just to break those bonds. It’s expensive. It’s slow. And it’s the reason why many old gas station sites are still "active" cleanup zones decades later.

What People Often Get Wrong

A common misconception is that MTBE was a "failure" of science. Honestly, it was a success of chemistry but a failure of systems thinking. It solved the air pollution problem it was designed to solve. The scientists just didn't weigh the "water solubility" risk against the "air quality" gain heavily enough.

Another myth is that it's "banned everywhere." Nope. If you're driving a car in Europe, there's a good chance there's some MTBE or its cousin, ETBE (ethyl tert-butyl ether), in your tank. The difference is that European regulations on underground storage tanks are often stricter, and they have different water usage patterns.

👉 See also: How to Get Rid of Ads on Facebook Without Losing Your Mind

Technical Specs for the Curious

For those who need the hard data, here is what makes methyl tert-butyl ether behave the way it does:

The vapor pressure is about 245 mmHg at 25°C. This makes it very volatile. Its water solubility is roughly 42 grams per liter. Compare that to benzene, which is only about 1.8 grams per liter. That's a massive difference. That solubility is why it’s such a persistent groundwater contaminant. It doesn't just "float" on the water table like a typical oil slick; it dissolves into the "bulk" of the water.

Moving Forward: Actionable Insights

If you are a property owner, a hobbyist chemist, or just someone concerned about their local environment, here are the real-world steps you should consider regarding MTBE.

1. Test Your Well Water

If you live within a mile of a current or former gas station and you use a private well, get a VOC (Volatile Organic Compound) scan. Most standard "potability" tests don't check for MTBE. You have to ask for it specifically. If you smell anything "turpentine-like," stop drinking it immediately.

2. Evaluate Filtration Options

Standard carbon filters (like the ones in your fridge) can remove MTBE, but they get "spent" very quickly because MTBE doesn't stick to carbon as well as other chemicals do. You need a high-quality, large-volume granulated activated carbon (GAC) system if you actually have a contamination issue.

3. Laboratory Safety

If you’re using MTBE as a solvent in a workshop or lab setting, treat it with respect. While it’s "safer" than diethyl ether regarding peroxides, it is still highly flammable. Always use it in a well-ventilated area because those vapors are heavier than air and will "crawl" along the floor to find an ignition source like a pilot light.

4. Check Local EPA Records

Most states have an online database of "Leaking Underground Storage Tanks" (LUST). It's worth a look to see if your neighborhood has a history of fuel spills. Knowledge is power here.

5. Industrial Alternatives

If you are in a manufacturing or cleaning role looking for a solvent, consider if "bio-based" solvents or even ETBE might be a better fit. ETBE is often seen as a slightly more "renewable" version since the ethanol component can be derived from crops, though it shares many of the same groundwater risks.

The story of methyl tert-butyl ether is really a cautionary tale about how we solve one environmental crisis only to accidentally trigger another. It’s a powerful tool that we simply didn't know how to contain. Today, it remains a vital industrial chemical, provided we keep it out of the pipes.