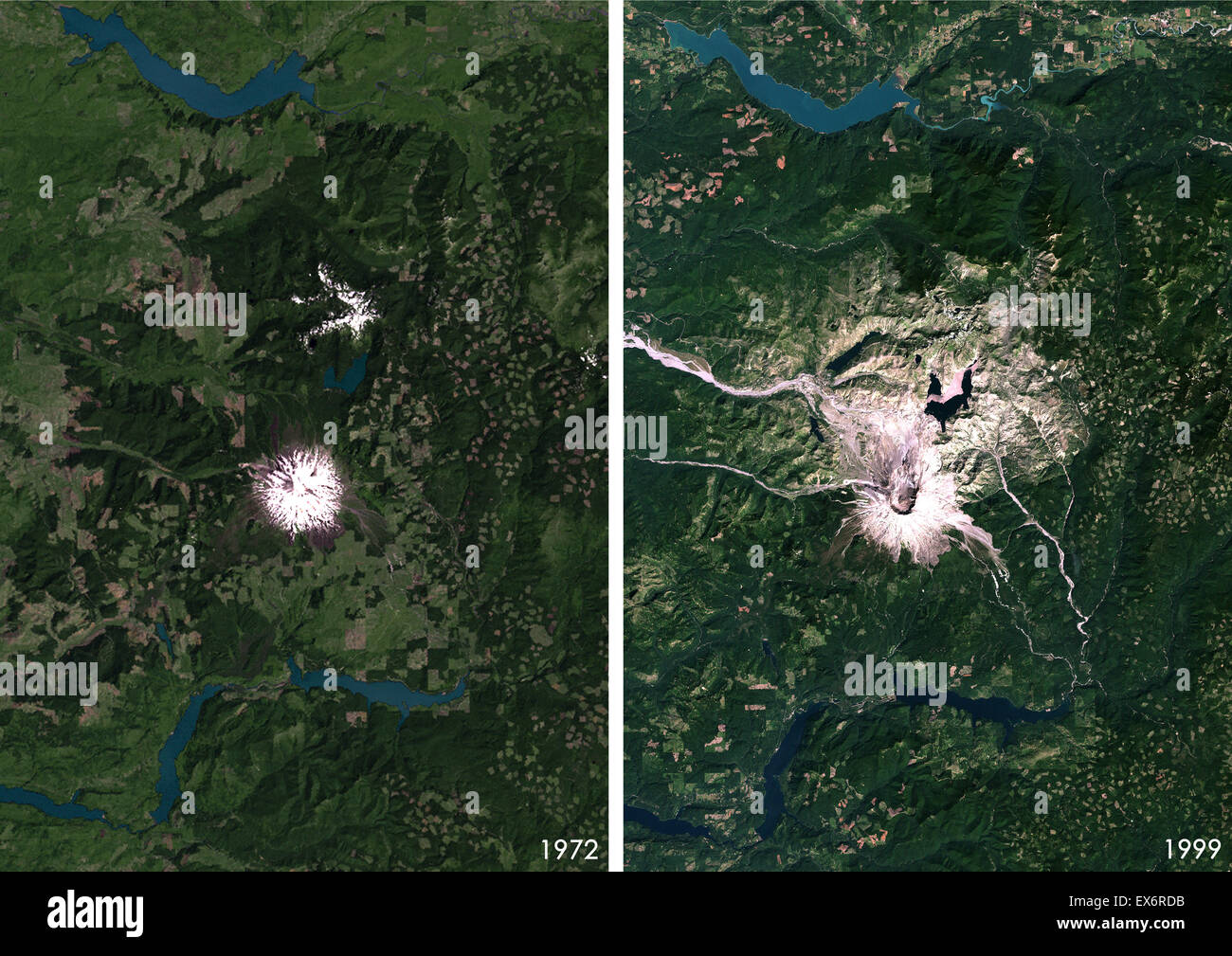

It’s hard to wrap your head around the fact that a mountain can just... go away. One minute, you have this "Mount Fuji of America," a symmetrical, snow-capped peak reaching 9,677 feet into the Washington sky. The next, you’ve got a jagged, hollowed-out crater that looks more like a lunar wasteland than the Pacific Northwest. If you look at the Mt St Helens eruption before and after photos, the first thing you notice isn't just the gray ash; it’s the shape. The mountain lost 1,313 feet of its summit in seconds. It didn't just blow its top like a cork; the entire north face slid off.

Honestly, the scale of it is terrifying. Before May 18, 1980, Spirit Lake was this pristine, turquoise mirror. People vacationed there. Harry R. Truman, the guy who famously refused to leave his lodge, lived there with his 16 cats. He thought the danger was overblown. He was wrong. When the mountain went, it triggered the largest terrestrial landslide in recorded history. That landslide slammed into Spirit Lake, displaced all the water in a 600-foot wave, and then dumped hundreds of feet of debris on top of where the lodge used to be. Truman and his cats are still down there, buried under roughly 150 feet of volcanic rock and ash.

The Warning Signs Nobody Really Understood

Geologists knew something was up. By March 1980, the mountain was waking up from a 123-year nap. Small earthquakes started rattling the area. Then came the "bulge." This is the part of the Mt St Helens eruption before and after story that usually gets glossed over in textbooks. Because magma was pushing up inside the volcano, the north flank started growing outward. It was swelling at a rate of about five feet per day.

Imagine a mountain moving that fast.

David Johnston, a 30-year-old volcanologist with the USGS, was stationed on a ridge about six miles away. He was monitoring that bulge. He knew it was unstable, but nobody predicted a lateral blast. Most volcanoes erupt upward. This one didn't. At 8:32 a.m., a 5.1 magnitude earthquake caused that bulging north face to simply give up. It collapsed. The pressure inside the volcano—which had been bottled up like a shaken soda bottle—exploded sideways. Johnston’s last words over the radio were, "Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!" He was gone seconds later.

🔗 Read more: Weather in Fairbanks Alaska: What Most People Get Wrong

The Landscape Shift: Total Annihilation

The "before" was a dense, old-growth forest. Douglas firs and Western hemlocks that had stood for centuries. The "after" was a graveyard of "bobby pins." That’s what they called the trees that were snapped off like toothpicks and stripped of their bark by the heat and force of the blast. The lateral blast traveled at over 300 miles per hour. It didn't just knock trees over; it sandblasted them. If you visit the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument today, you can still see these downed logs all pointing in the same direction—away from the crater. It’s a compass made of dead trees.

The temperature of the gas and rock—the pyroclastic flow—reached 1,300 degrees Fahrenheit. It’s a kind of heat that doesn't just burn; it vaporizes.

- The Blast Zone: 230 square miles of forest were leveled.

- The Ash Fall: It turned day into night in Yakima and Ritzville. People were wearing pantyhose over their car air filters just to keep the engines from seizing.

- The Lahars: Volcanic mudflows (lahars) had the consistency of wet concrete and moved fast enough to tear bridges off their foundations.

Life Finds a Way (Slowly)

People thought the area would be a moonscape forever. They were wrong about that, too. One of the most fascinating aspects of the Mt St Helens eruption before and after comparison is the biological recovery. It started with a gopher. Because pocket gophers live underground, some survived the initial heat. When they started digging back up, they brought fresh, un-ashed soil to the surface. This soil contained seeds and fungi that helped plants like lupine take root.

Lupines are "pioneer" plants. They have these little nodules on their roots that "fix" nitrogen, basically fertilizing the volcanic ash so other things can grow. Today, the "Pumice Plain"—which was once a scorching field of sterile rock—is covered in wildflowers, willow thickets, and even some young evergreens. It’s not the forest it was, but it’s alive.

💡 You might also like: Weather for Falmouth Kentucky: What Most People Get Wrong

Why the Pumice Plain Matters

Scientists like Charlie Crisafulli have spent decades studying this specific patch of dirt. It’s a living laboratory. We’ve learned that nature doesn't need a "reset" button; it just needs time and a few stubborn gophers. You’ll see elk herds grazing in the crater’s shadow now. They follow the same paths their ancestors did, even though the geography has fundamentally changed.

Visiting Today: What You'll Actually See

If you drive up to Johnston Ridge Observatory (named after David Johnston), the view is sobering. You’re looking directly into the throat of the volcano. You can see the lava dome—a massive "plug" of rock that has been slowly growing inside the crater since the 80s. The mountain is still active. It erupted again between 2004 and 2008, though it was much quieter—mostly just oozing thick, pasty lava that built up the dome.

The contrast is wild. On the south side of the mountain, it still looks like a lush Pacific Northwest forest. You can hike the Ape Caves (lava tubes from an eruption 2,000 years ago). But once you cross over to the north side, you enter the blast zone. The transition is jarring. It’s like a line drawn in the dirt: Life on one side, wreckage on the other.

Realities of the "After" Landscape

- Spirit Lake is a log mat. To this day, thousands of logs from the 1980 blast are still floating on the surface of the lake. They move around with the wind. From a distance, it looks like solid ground, but it’s just a giant, shifting carpet of dead trees.

- The Hummocks. As you hike near the Toutle River, you’ll see these weird, grassy mounds. Those aren't hills. They are actual chunks of the mountain's summit that landed there during the landslide. You’re literally walking on the old top of the mountain.

- The Toutle River is a mess. It’s still choked with volcanic sediment. Every time it rains hard, the river gets muddy and shallow because there’s just so much ash and debris still washing down from the mountain.

Survival Stories and Statistics

57 people died. That number could have been in the thousands if the eruption had happened on a workday instead of a Sunday morning, or if the "red zone" hadn't been evacuated. Some were loggers, some were photographers like Robert Landsburg—who realized he couldn't escape and spent his final seconds filming the cloud and then cushioning his camera with his body so the film would survive. He knew the importance of documenting the "after."

📖 Related: Weather at Kelly Canyon: What Most People Get Wrong

The ash traveled around the world in 15 days. It didn't just affect Washington; it was a global event.

Moving Forward: Actionable Insights for Your Visit

If you’re planning to see the Mt St Helens eruption before and after legacy in person, don't just go to the main visitor center and leave.

- Check the Webcam: Before you drive two hours, check the USGS Mount St. Helens webcam. The mountain creates its own weather, and it’s often shrouded in clouds even when it’s sunny in Portland or Seattle.

- Hike the Hummocks Trail: It’s an easy loop that lets you see the landslide debris up close. It’s the best way to feel the scale of the collapse.

- Look for the "Lupine Blankets": If you go in early summer, the contrast of purple flowers against the grey ash is the best visual representation of the mountain's recovery.

- Respect the Closures: Large parts of the blast zone are still restricted for scientific research. Stay on the trails. The crust of the ash is fragile, and walking on it can disrupt the slow process of soil formation.

The mountain is shorter now, and it’s missing a huge chunk of its heart. But in a weird way, it’s more interesting than it was before. It’s no longer just a pretty postcard; it’s a visceral reminder that the ground beneath our feet isn't nearly as permanent as we like to think.

To get the most out of your trip, start at the Silver Lake Visitor Center for the historical context, then head to the Science and Learning Center at Coldwater, and finish at Johnston Ridge. Walking that path takes you through the timeline of the disaster and the slow, grinding return of the green. It’s a story of total destruction, sure, but also one of incredible resilience.