Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was on a tear in 1784. Imagine being so prolific that you’re finishing masterpieces faster than the ink can dry. That spring, he was the toast of Vienna, playing nearly 20 concerts in just two months. But amidst the frenzy of his own superstar schedule, he wrote something special for someone else.

That something was Piano Concerto 17 in G major, K. 453.

It wasn't for his own subscription concerts, though he certainly could have used it. Instead, he wrote it for his student, Barbara "Babette" Ployer. She was the daughter of a Salzburg official, and honestly, she must have been a powerhouse on the keys. You don’t write music this harmonically daring or technically exposed for a casual hobbyist.

If you’ve ever wondered why this specific concerto feels different from the "dark" or "stormy" Mozart, it’s because it’s basically sunlight captured on parchment. But don't let the "sunny" G major key fool you. It’s got a strange, almost obsessive side that musicologists still argue about.

Why Piano Concerto 17 in G Major Hits Different

Most of Mozart’s Viennese concertos were written for him to perform. They were "marketing materials" for his brand. But because he wrote this for a student, there's a unique sense of clarity and "teaching" embedded in the score.

👉 See also: Album Hopes and Fears: Why We Obsess Over Music That Doesn't Exist Yet

The March That Isn't a March

The first movement, Allegro, starts with a march rhythm. Now, usually, a 1780s march sounds like a bunch of soldiers stomping through the mud. Not here. Mozart takes that stiff "left-right-left" beat and softens it with woodwinds. The flutes and oboes basically giggle over the strings. It’s elegant. It’s light.

But then, out of nowhere, he throws in these "distant" harmonies. One minute you're in a comfortable ballroom, and the next, you’ve stepped into a shadowy hallway you didn't know existed. This is the Mozart "magic trick"—making complex musical shifts feel like a natural conversation.

The Weird Mystery of the Starling

Okay, here’s the part everyone loves. A few weeks after finishing this piece, Mozart bought a pet starling. According to his diary, he paid 34 kreuzer for it. Why? Because the bird could whistle the theme from the finale of Piano Concerto 17.

Mozart actually wrote the bird’s version of the tune in his notebook. The bird, being a bird, got one note "wrong" (it sang a G-sharp instead of a G-natural). Mozart thought this was hilarious. He wrote "Das war schön!" (That was beautiful!) next to it.

✨ Don't miss: The Name of This Band Is Talking Heads: Why This Live Album Still Beats the Studio Records

There’s a persistent debate about who taught who. Did the bird hear Mozart whistling it and copy him? Or did the bird already know a similar folk tune? Either way, the bird was a member of the family for three years. When it died, Mozart didn't just toss it in the garden. He held a full funeral with veiled mourners and read a poem he wrote for it.

The Movements: A Breakdown

If you're listening to this for the first time, keep an ear out for how the "star" of the show shifts. It’s not just the piano; the woodwinds are basically equal partners here.

- I. Allegro: It’s all about thematic wealth. Most concertos have two main themes. Mozart, being a bit of an overachiever, crams about six into the opening. It’s like he had too many good ideas and couldn't bear to cut any of them.

- II. Andante: This is the "opera" moment. The piano acts like a soprano. There are these long, dramatic pauses that make you lean in. The woodwinds act like a choir responding to the soloist. It’s surprisingly melancholy for a G major work.

- III. Allegretto – Presto: This is the bird-song movement. It’s a series of five variations on that simple, folk-like tune. It feels like a sunny day in the park until the "Presto" coda hits. Suddenly, the tempo doubles, and it turns into a frantic, comic opera finale.

Barbara Ployer: The Woman Who Could Play

We often forget that Mozart’s students were elite musicians. Barbara Ployer didn't just "play a bit." She debuted this work on June 13, 1784, at her uncle’s house in Döbling. Mozart invited the famous Italian composer Giovanni Paisiello just to show off what his student (and his music) could do.

He didn't just give her the G major concerto either. He also wrote the Piano Concerto No. 14 (K. 449) for her. It’s clear he respected her technique. In Piano Concerto 17, the soloist is "exposed." There aren't many places to hide behind a loud orchestra. You need a clean, singing touch and a lot of finger independence.

🔗 Read more: Wrong Address: Why This Nigerian Drama Is Still Sparking Conversations

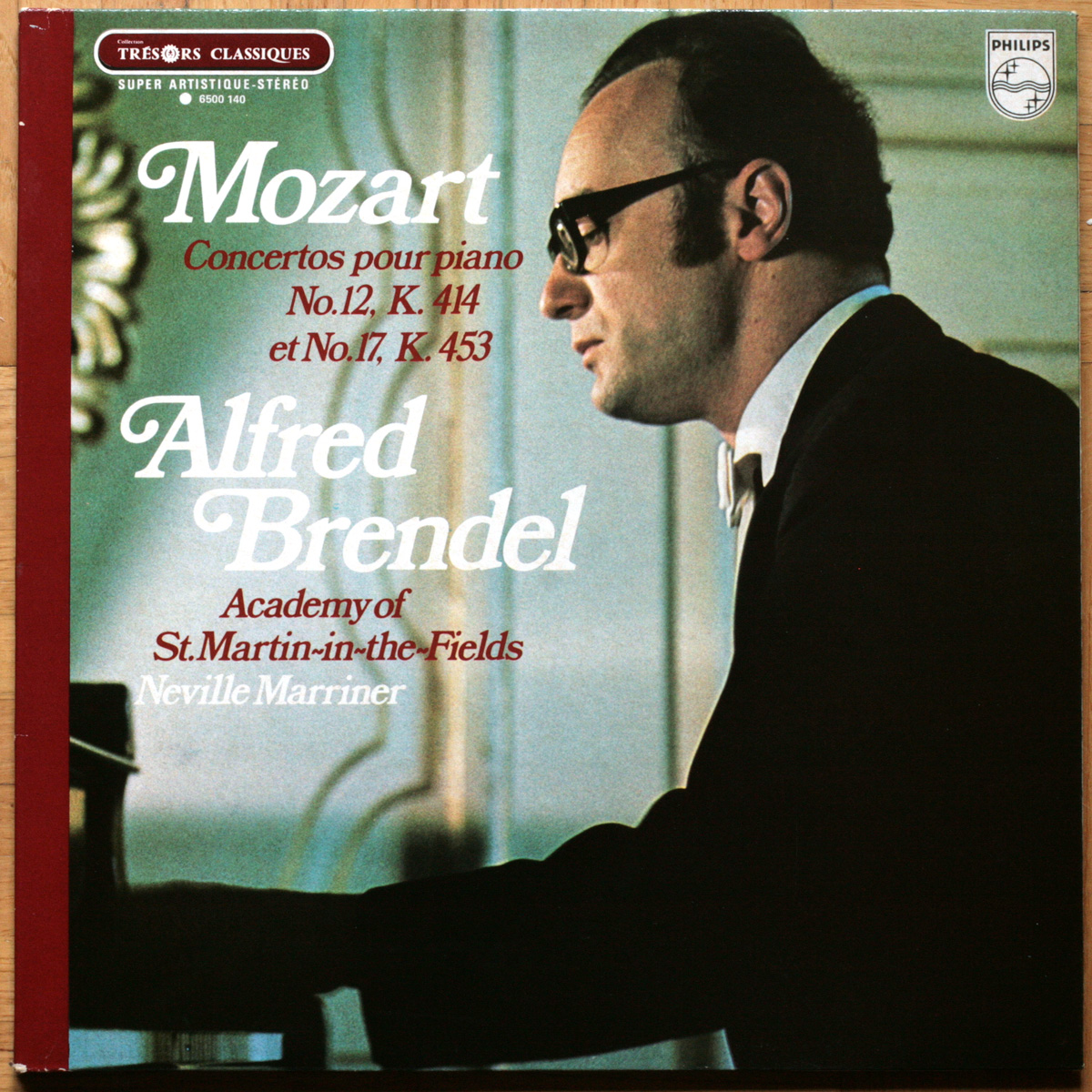

Which Recording Should You Listen To?

Look, everyone has an opinion on Mozart. Some like it "pretty," others like it "muscular." If you want the gold standard, you can't go wrong with Mitsuko Uchida with the English Chamber Orchestra. She plays with this crystal-clear precision that makes every note feel like a little pearl.

If you’re into the historical vibe, check out Olga Pashchenko on the fortepiano. The instrument sounds different—more "woody" and intimate, less like a modern grand piano. It probably sounds closer to what Barbara Ployer heard in her uncle’s living room.

For something a bit more modern and vibrant, Leif Ove Andsnes does a fantastic job conducting from the keyboard. It gives the whole thing a chamber music feel, where the piano and orchestra are truly "talking" to each other.

Why This Piece Still Matters

Honestly, Piano Concerto 17 is the perfect entry point into Mozart’s genius. It’s not as "heavy" as the 20th or as "grand" as the 21st, but it’s arguably more clever. It’s the sound of a man who was deeply happy, creatively unblocked, and apparently, very fond of his bird.

It reminds us that even the greatest "high art" often comes from the simplest places—a student’s progress, a catchy march, or a pet that won't stop whistling in the corner of the room.

Actionable Listening Steps

- Queue up the third movement first. Listen for the "Starling Theme" and see if you can spot where the bird might have chirped that "wrong" note.

- Compare two versions. Listen to a modern piano version (like Uchida) and then a fortepiano version. Notice how the woodwinds stand out more when the piano isn't so "big."

- Watch for the pauses. In the second movement (Andante), count how many times the music just... stops. That’s Mozart playing with your expectations.