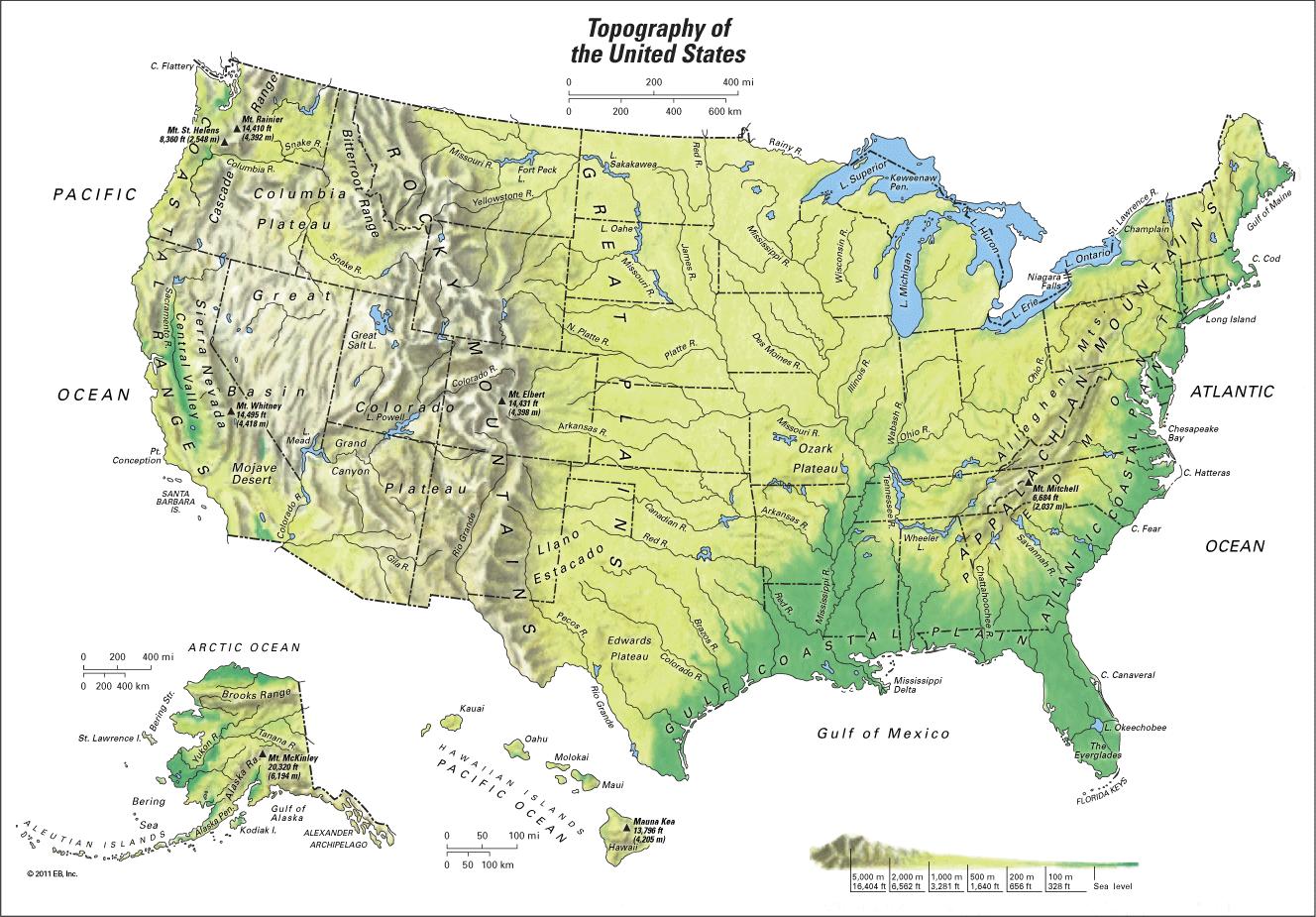

America is tall. That sounds like a weird way to start, but if you actually look at a topographical map of the mountain ranges of the US, you realize the country isn't just a flat slab with a few bumps on the edges. It’s a jagged, tectonic mess. Most people think of the Rockies and the Appalachians and call it a day, but that’s barely scratching the surface of what’s actually happening out there.

We've all seen the postcards of the Tetons. They’re gorgeous, obviously. But have you ever stood in the middle of the Basin and Range province in Nevada? It feels like the earth is literally ripping apart, because, well, it is.

The reality is that our mountains define everything from our weather to where our cities sit. If the Sierra Nevada didn't exist, California would be a very different, much drier place. If the Appalachians were as tall today as they were 300 million years ago, the East Coast would look like the Himalayas. Scale matters.

The Old Guard: Why the Appalachians Are Weirder Than You Think

When you look at the mountain ranges of the US on the East Coast, you’re looking at ghosts. The Appalachian Mountains are old. Like, "predates the Atlantic Ocean" old. Geologists like those at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) will tell you these peaks used to rival the Alps or the Rockies. Now? They’re rounded, green, and honestly, a bit humble.

But don't let the height fool you. The Appalachian system isn't just one long ridge. It’s a complex network including the Blue Ridge, the Great Smokies, and the White Mountains up in New Hampshire.

Ever driven the Blue Ridge Parkway? It’s not just a pretty road. It’s a traverse through some of the oldest exposed rock on the planet. The diversity of salamanders in the Great Smokies is higher than almost anywhere else on Earth. Why? Because these mountains have been stable for so long that evolution just went wild in the damp, cool coves. It’s an ancient ecosystem that survived while other ranges were still being pushed up by tectonic plates.

The Rocky Mountains: The Spine of the Continent

The Rockies are the heavy hitters. Stretching from New Mexico all the way up through Canada, they are the literal divide of the continent. If a raindrop falls on one side of the Continental Divide, it’s heading to the Atlantic. A few inches to the west? It’s going to the Pacific.

🔗 Read more: City Map of Christchurch New Zealand: What Most People Get Wrong

Most people don't realize the Rockies aren't just one big pile of rock. They’re broken into distinct sub-ranges like the Front Range near Denver, the Wind River Range in Wyoming, and the Bitterroots in Montana.

The geology here is actually kind of a mystery. Usually, mountains form right at the edge of a continent where plates collide. But the Rockies are hundreds of miles inland. This happened because of something called "flat-slab subduction." Basically, an oceanic plate slid underneath North America at such a shallow angle that it didn't sink into the mantle right away. Instead, it scraped along the bottom of the crust, pushing up the Rockies far from the coast. It’s like sliding a rug across a floor and watching it bunch up in the middle.

The High Peaks and Oxygen Debt

If you’ve ever tried to hike a 14er (a peak over 14,000 feet) in Colorado, you know the physical toll. Mount Elbert is the highest point in the Rockies at 14,440 feet. It’s a slog. The air is thin, the weather turns in seconds, and the scale is just massive.

- Colorado has 58 peaks over 14,000 feet.

- The weather can drop 30 degrees in twenty minutes.

- Lightning is a very real, very scary threat above the treeline.

The Sierra Nevada and the Cascades: Fire and Ice

Moving further west, things get even more dramatic. The Sierra Nevada in California is essentially one giant block of granite that tilted upward. This is home to Mount Whitney, the highest point in the contiguous United States.

John Muir called it the "Range of Light." He wasn't being poetic—or well, he was—but he was also being literal. The light-colored granite reflects the sun in a way that makes the whole range glow at dusk.

Then you have the Cascades. This is where the "fire" part comes in. Unlike the granite blocks of the Sierra, the Cascades are a volcanic arc. We’re talking about Mount Rainier, Mount St. Helens, and Mount Hood. These are active volcanoes. They’re beautiful, but they’re also a reminder that the Pacific Northwest is sitting on a massive subduction zone.

💡 You might also like: Ilum Experience Home: What Most People Get Wrong About Staying in Palermo Hollywood

If you visit Crater Lake in Oregon, you’re standing in the collapsed remains of Mount Mazama, which blew its top about 7,700 years ago. It was one of the largest eruptions in recent geological history. The lake is now the deepest in the US because it’s basically just a giant, water-filled hole in a volcano.

The Basin and Range: The Forgotten Mountains

This is the part of the mountain ranges of the US map that people usually fly over. Between the Sierra Nevada and the Rockies lies the Great Basin. It covers almost all of Nevada and parts of Utah and Arizona.

Imagine a washboard. That’s the Basin and Range.

The crust here is stretching. As it pulls apart, some blocks of earth drop down (the basins) and others tilt up (the ranges). There are over 300 mountain ranges in Nevada alone. Most people think Nevada is just a flat desert, but it’s actually the most mountainous state in the lower 48 if you count the total number of individual ranges.

The Ruby Mountains are a hidden gem here. They look like the Swiss Alps but are surrounded by high-desert sagebrush. It’s weird, jarring, and absolutely beautiful.

Alaska: The Real Giants

We have to talk about Alaska. Honestly, the mountains in the lower 48 are "hills" compared to the Alaska Range. Denali stands at 20,310 feet.

📖 Related: Anderson California Explained: Why This Shasta County Hub is More Than a Pit Stop

But it’s not just the height; it’s the base-to-peak rise. Denali rises about 18,000 feet from its base, which is a greater vertical rise than Mount Everest. When you see it, it looks fake. It’s too big for the horizon to hold.

The Saint Elias Mountains on the border of Alaska and Canada are the highest coastal mountains in the world. They go from sea level to 18,000 feet in a ridiculously short distance. This creates some of the most intense weather on the planet because the mountains act like a giant wall for moisture coming off the Gulf of Alaska.

How to Actually Experience These Ranges

If you're planning to explore the mountain ranges of the US, you need to understand that "mountain" means something different depending on where you are.

In the East, it’s about the forest. The Appalachian Trail is a green tunnel. You won't get the sweeping vistas every five minutes, but you get a sense of deep, ancient history. You'll want good waterproof gear, because it’s going to rain. A lot.

Out West, it’s about the exposure. You’re often above the trees. The sun will fry you, and the wind will beat you down. You need layers. You also need to respect the "rain shadow" effect. The west side of the Cascades is a rainforest; the east side is a desert. That’s the power of these ranges—they literally dictate who gets water and who doesn't.

Practical Tips for Mountain Travel

- Check the SNOTEL data. If you’re heading into the Rockies or Sierras in the spring, look at Snow Telemetry (SNOTEL) sites. It tells you how much snow is actually left. Just because it’s 80 degrees in Denver doesn't mean the trails at 11,000 feet are clear.

- Hydrate more than you think. High altitude dries you out before you even feel thirsty.

- Download offline maps. Google Maps will fail you the second you enter a canyon in the Wind River Range. Use apps like OnX or Gaia GPS and download the layers before you lose cell service.

- Acclimatize. Don't fly from sea level to Leadville, Colorado, and try to hike a peak the next day. Your blood literally needs time to produce more red blood cells to carry oxygen. Give it 48 hours.

The mountain ranges of the US aren't just scenery. They are the scaffolding of the continent. Whether it's the volcanic peaks of the Northwest or the ancient, folded ridges of the East, these landscapes shape the American experience. They’re big, they’re messy, and they’re definitely worth the drive.

To start your own journey, grab a physical gazetteer for a state like Colorado or West Virginia. Digital maps are great, but seeing the contour lines on a large-scale paper map is the only way to truly appreciate the sheer verticality of this country. Head to a National Forest instead of a National Park if you want to avoid the crowds; the views are often just as good, and the silence is a lot deeper.