You're sitting at a coffee shop on First Street in downtown Mount Vernon, maybe grabbing a latte at Ristretto, and you feel that slight vibration. Usually, it’s just a heavy truck rattling the old brick buildings. But sometimes, your brain goes straight to the big one. It's a valid fear. If you live in Skagit County, the phrase earthquake Mount Vernon WA isn't just a search term; it’s a lingering "when," not an "if."

Living here is beautiful, but we are essentially sitting on a geological ticking clock.

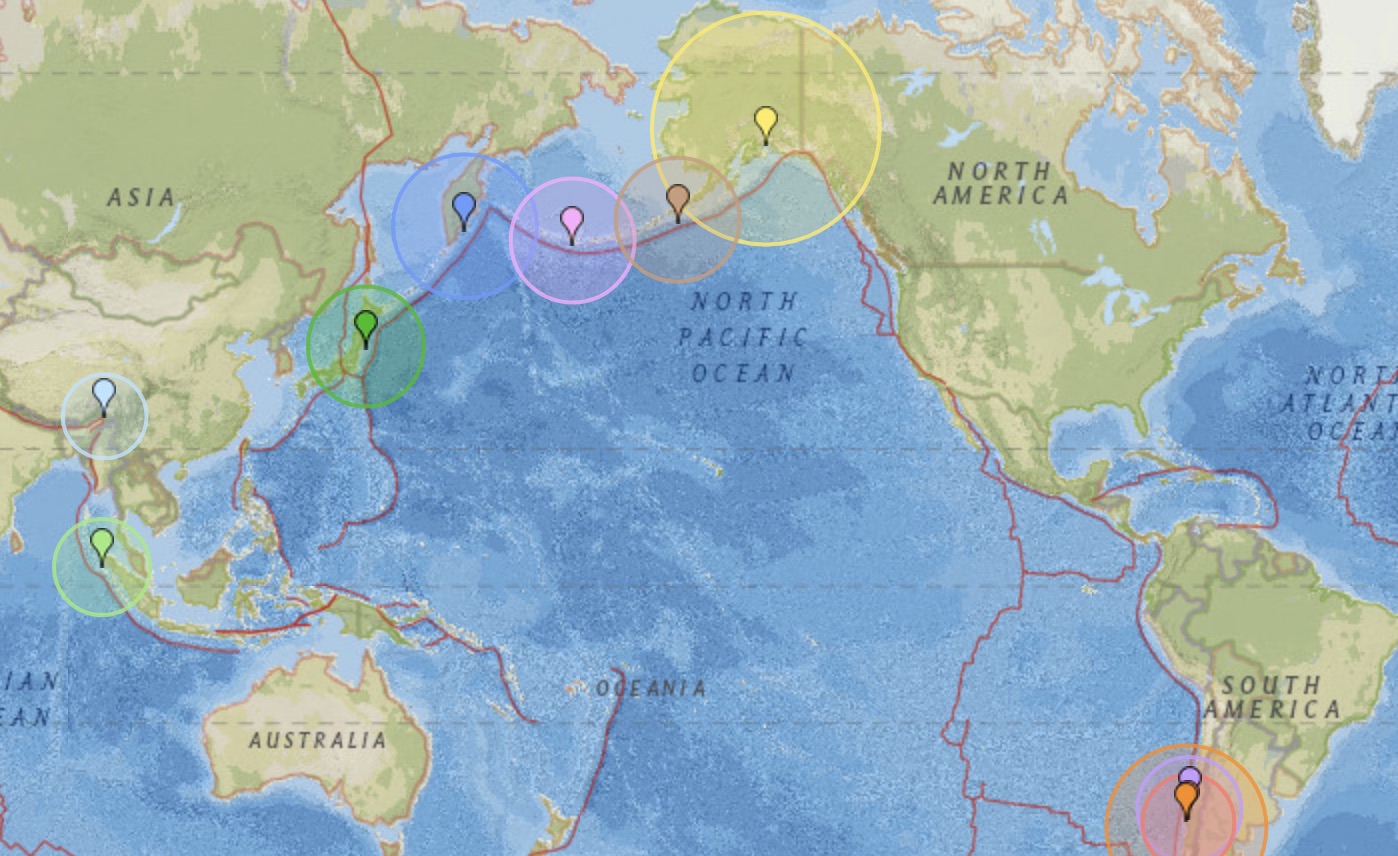

People often think about the "Big One"—the massive Cascadia Subduction Zone quake—and they aren't wrong to worry about it. However, most folks in Mount Vernon completely overlook the literal cracks right under their feet. We’re talking about crustal faults. These are shallower, more localized, and in some ways, way more terrifying for Skagit Valley residents than a quake centered out in the Pacific Ocean.

The Devil We Don't Know: The Devils Mountain Fault

When people talk about a potential earthquake in Mount Vernon WA, they usually point toward the coast. But have you looked at the Devils Mountain Fault? It’s a nasty piece of work. This fault line runs right through the heart of Skagit County, stretching from the North Cascades all the way across to Vancouver Island.

It’s active.

Geologists like Brian Sherrod from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) have done the dirty work of digging trenches to see what this fault has done in the past. The data is sobering. The Devils Mountain Fault Zone is capable of producing a Magnitude 7.0 or higher. To put that in perspective, the Nisqually quake in 2001 was a 6.8, and that was deep underground. A shallow 7.5 on the Devils Mountain Fault would be a complete game-changer for downtown Mount Vernon’s unreinforced masonry buildings.

The scary part? These crustal faults don't give much warning. While the subduction zone quakes happen every 300 to 500 years like clockwork (we are currently at year 326 since the last one in 1700), crustal faults are much more erratic. They can stay quiet for thousands of years and then snap with enough force to liquefy the very ground you're standing on.

📖 Related: 7 day weather forecast columbia sc: Why This Week is Kinda Wild

Why Mount Vernon is a "Liquid" City

If you’ve ever tried to dig a post hole in the Skagit Valley, you know the soil is basically just river silt and clay. It's great for tulips. It's absolute garbage for earthquakes.

This brings us to liquefaction.

When a major earthquake hits Mount Vernon WA, the high water table and loose, sandy river deposits undergo a physical transformation. The shaking increases the water pressure between the soil grains. Suddenly, the solid ground starts acting like a thick liquid. Buildings don't just shake; they sink. They tilt. The historic district of Mount Vernon, with its beautiful but heavy brick architecture, is particularly vulnerable to this phenomenon.

Imagine the Skagit River levees. We spend so much time worrying about them breaching during a flood. Now, imagine those same earthen walls shaking violently. If the soil underneath them liquefies, the levees could slump or fail entirely. You could have a seismic event followed immediately by a massive flooding event. It's a "worst-case" scenario that emergency planners in Skagit County are actually paid to worry about.

Comparing the "Big One" to the "Local One"

It’s helpful to understand the different flavors of disaster we might face. Honestly, it’s about depth and distance.

- The Cascadia Subduction Zone (The Big One): This is the monster. It’s 100 miles offshore. The shaking would last for 3 to 5 minutes. In Mount Vernon, it would feel like being on a boat in a rough sea. Long, rolling waves. It would break bridges and drop the viaducts, but because it's far away, the "sharp" jolts are dampened.

- Deep Intraplate Quakes (Nisqually Style): These happen 30-50 miles down. They happen more often. They break chimneys and crack plaster, but they rarely level cities.

- Crustal Faults (Devils Mountain / Darrington-Devils Mountain): This is the local threat. It’s shallow—maybe only 10 miles deep. The shaking is violent, jerky, and high-frequency. This is what knocks buildings off their foundations.

If you're in a wood-frame house in a newer development up on the hill near Big Rock Park, you're actually in a decent spot. Wood is flexible. It moves. But if you’re down in the valley floor, your house is essentially sitting on a bowl of Jell-O.

The Infrastructure Headache

Let's talk about the I-5 bridge over the Skagit River. We all remember when it collapsed in 2013 because a truck hit it. Now imagine a Magnitude 7.2 earthquake in Mount Vernon WA ripping through that corridor.

The Skagit River bridges are the lifeblood of the I-5 corridor. If they go down, the county is effectively cut in half. Burlington and Mount Vernon become islands. Local emergency services, like Skagit Valley Hospital, have done significant retrofitting, but the sheer logistics of a post-quake Skagit Valley are a nightmare.

✨ Don't miss: Channel 3 News Burlington Explained: What Really Happened to Vermont’s First Station

The city has been proactive, though. The downtown flood wall—that massive project everyone watched for years—isn't just for water. It was engineered with some seismic considerations. But you can't retrofit an entire valley of silt.

What Actually Happens During the Shaking?

When it starts, you won't hear a roar like in the movies. It’s usually a sharp bang, like a car hit your house. Then the swaying begins. In Mount Vernon, because of the soft soil, that swaying is amplified.

I’ve talked to people who were in the valley during smaller tremors. They describe a "sea-sick" feeling. That’s the sediment responding to the waves.

Common misconception: "I'll run outside."

Wrong.

In a place like downtown Mount Vernon, running outside is the fastest way to get hit by a falling brick "parapet" or a piece of a 100-year-old cornice. The safest place is under a sturdy table. If you're in the valley, stay put.

The Tsunami Question

People often ask if a Mount Vernon WA earthquake would cause a tsunami. Generally, no—not directly in the city. Mount Vernon is far enough inland and elevated enough that a Pacific Coast tsunami wouldn't reach it. However, a "seiche"—a standing wave in an enclosed body of water—could happen in Clear Lake or Big Lake. And if a quake triggered a massive landslide into the Skagit River, you could see a localized surge of water. But the "30-foot wall of water" is a coast problem, not a valley problem.

Practical Steps for Skagit Residents

Look, we can't move the fault lines. We aren't going to stop living in one of the most beautiful places on Earth just because the ground is grumpy. But being "Skagit Ready" is different than being "Seattle Ready."

📖 Related: Universal Credit Sanctions: What Most People Get Wrong About Falling Foul of the DWP

- Check your foundation. If you live in an older home near the city center, check if it's actually bolted to the foundation. Many pre-1950s homes in Mount Vernon are just "resting" there. A few thousand dollars in bolts can save a $500,000 house.

- Water is your biggest enemy. In a major quake, the city water lines—which cross the river and run through liquefiable soil—will snap. You won't have water for weeks. Not days. Weeks. You need at least 14 days of water stored.

- The "Skagit Split" Plan. Since the river divides the area, have a plan for if you are in Burlington and your family is in Mount Vernon when the bridges go. Where do you meet? Don't count on cell service. The towers will be jammed or down.

- Automatic Gas Shut-off. If the ground moves, your gas line might leak. An automatic shut-off valve is a cheap insurance policy against your house burning down after the shaking stops.

- Secure your water heater. This is the #1 source of indoor flooding and a great backup source of 50 gallons of drinking water if it doesn't tip over. Use heavy-duty straps, not the flimsy ones.

The Reality Check

The USGS and the Washington State Department of Natural Resources (DNR) continue to map the Skagit Valley. Every few years, we find a new "splinter" of a fault. It sounds scary, but knowledge is actually power here. Knowing that the earthquake risk in Mount Vernon WA is tied to specific soil types helps us build better.

We saw what happened in Christchurch, New Zealand, in 2011. That was a city built on similar soil to Mount Vernon. The damage was extensive because of liquefaction. We've learned from them. Modern building codes in Washington are some of the toughest in the world, and newer construction in the Skagit Highlands is built to withstand significant movement.

The historic charm of our valley is its greatest asset, but also its biggest seismic vulnerability. We have to balance preserving the character of the Skagit with the cold, hard reality of plate tectonics.

Don't wait for the next "vibration" to think about this. Secure your bookshelves today. Buy that extra flat of canned food at Costco. Talk to your neighbors. In a valley as tight-knit as ours, we’re going to be the ones pulling each other out of the rubble long before the state or federal help arrives.

Next Steps for Safety:

- Identify your soil type: Check the Washington DNR Geologic Hazard Map to see if your home sits on a high-liquefaction zone.

- Retrofit: Contact a local contractor to evaluate your home's "seismic tie-downs," especially if the house was built before 1990.

- Emergency Kit: Build a 2-week kit specifically focusing on water filtration, as the river-based water systems are highly vulnerable to seismic disruption.