Honestly, if you grew up in the Pacific Northwest, you’ve probably seen the grainy, terrifying shots of the sky turning black in the middle of the day. But when most people go looking for mount st helens eruption photos, they expect to see a single, perfect video of the mountain blowing its top.

Here is the kicker: that video doesn't exist.

Nobody actually caught the start of the 1980 eruption on a motion picture camera. We have thousands of stills and plenty of "after" footage, but the iconic "sequence" everyone remembers is actually a series of stop-motion photographs. It’s wild to think about. In an age where every minor fender bender is recorded by four different smartphones, the greatest geological event in modern American history was captured almost entirely on film rolls that people had to physically protect with their lives.

The Photos That Cost a Life

You can't talk about these images without mentioning Robert Landsburg. He was a freelance photographer from Portland, and he’d been obsessed with the mountain for weeks. On the morning of May 18, 1980, he was just a few miles from the summit. When the north flank collapsed, he realized instantly he wasn't going to make it out.

He didn't panic. He didn't drop the camera and run blindly.

Basically, he stayed. He kept taking photos as the pyroclastic cloud—a wall of ash and heat moving at hundreds of miles per hour—raced toward him. When he knew the end was seconds away, he did something incredibly methodical. He rewound the film into its canister, tucked the camera into his bag, and then laid his body on top of the bag. He was found 17 days later. Because of that human shield, his film survived the heat. Those photos, published later in National Geographic, are some of the most haunting things you’ll ever see. They show the wall of grey getting larger and larger until the frame goes dark.

👉 See also: Why the Recent Snowfall Western New York State Emergency Was Different

Why the Gary Rosenquist Sequence Matters

If you've seen the "animation" of the mountain sliding away, you're looking at Gary Rosenquist’s work. He was camping at Bear Meadow, about 11 miles out. Because he was using a camera with a motor drive, he managed to snap a series of 23 frames in about 40 seconds.

It’s the closest thing we have to a movie of the landslide.

Scientists at the USGS used these specific mount st helens eruption photos to calculate exactly how fast the mountain fell apart. It wasn't just an explosion; it was the largest terrestrial landslide in recorded history. Rosenquist’s shots show the "bulge" on the north side—which had been growing by five feet a day—simply giving up.

Most people think the mountain blew "up" like a cork in a bottle. Rosenquist’s photos prove it actually blew "out" sideways. That lateral blast is what caught everyone off guard. It moved at 300 miles per hour, overtaking the landslide itself. It’s sort of terrifying to realize that if Gary had been a mile closer, or if the wind had shifted, those photos would have ended up as melted plastic in the dirt.

The Lost Rolls and Goodwill Finds

Not every photographer was as lucky as Rosenquist, or as sacrificial as Landsburg. Reid Blackburn, a photographer for The Columbian, was also killed. His car was found buried in ash, and while his camera was recovered, the film inside was totally fried by the heat.

✨ Don't miss: Nate Silver Trump Approval Rating: Why the 2026 Numbers Look So Different

However, history has a weird way of resurfacing.

In 2013, a roll of film Reid had shot from a helicopter a month before the eruption was found in a box at the newspaper’s office. Developing it 33 years later felt like opening a time capsule. You see the mountain looking pristine, snow-covered, and deceptively peaceful.

Then there’s the Goodwill story from 2017. A photographer named Kati Dimoff bought an old Argus C2 camera for a few bucks at a Portland thrift store. Inside was an exposed roll of Kodachrome. When she got it developed, she found shots of the eruption taken from the Longview Bridge. The family who originally owned the camera had just... forgotten about it. Imagine having photos of a literal cataclysm sitting in a junk drawer for four decades.

How to Find High-Resolution Archives Today

If you are looking for the real deal—not the upscaled, AI-filtered versions floating around social media—you have to go to the source. The USGS (U.S. Geological Survey) maintains a massive digital archive.

- The Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument library has the most scientific data.

- The Oregonian and The Columbian archives hold the best "on the ground" human interest shots.

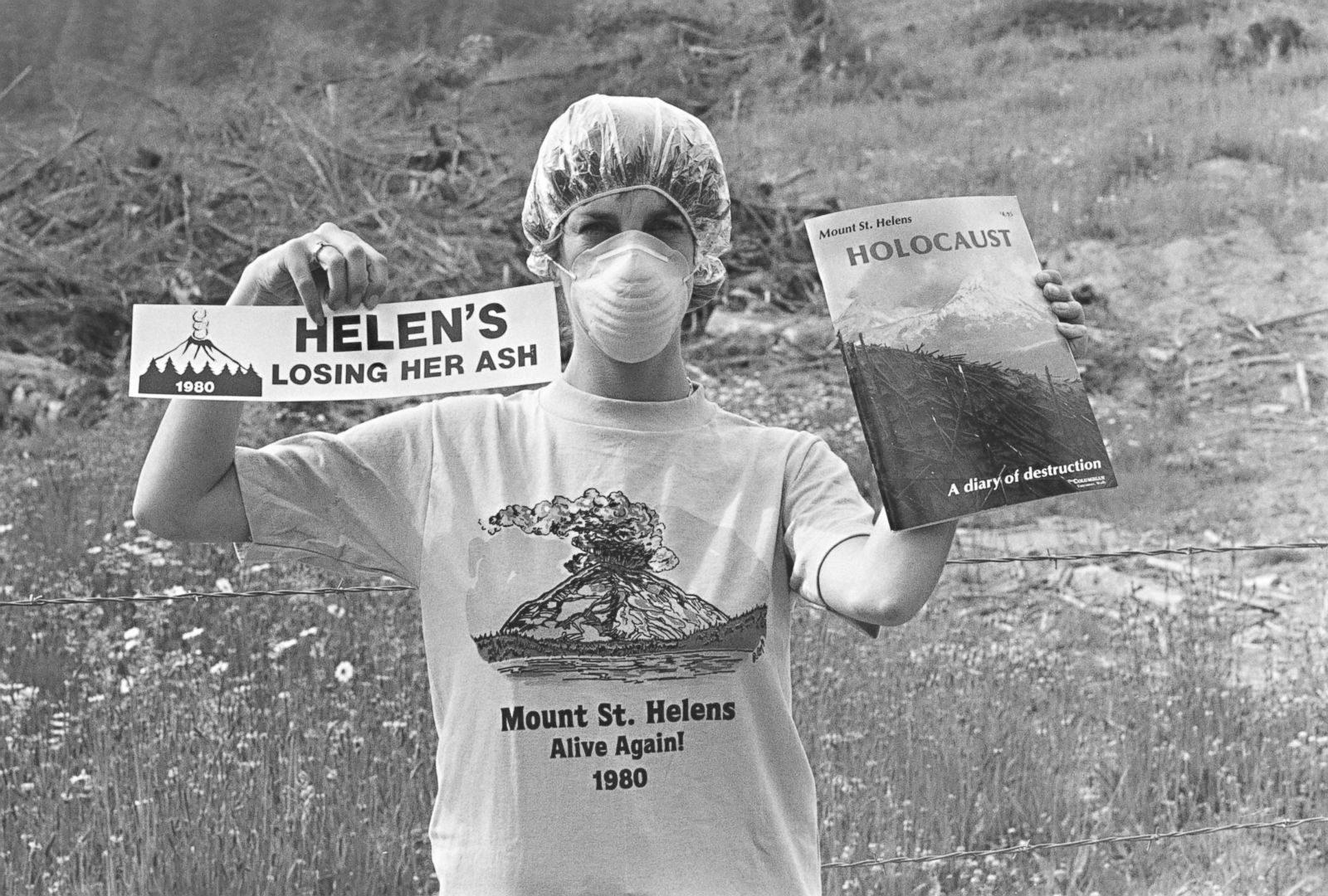

- Archives West contains the Reiner Decher collection, which features hundreds of slides of people actually watching the plume from distant ridges.

Avoid the "4K Upscaled" videos on YouTube if you want accuracy. Those often use "interpolation" which literally guesses what happened between the frames. It looks smooth, sure, but it’s not what the eye—or the lens—actually saw.

🔗 Read more: Weather Forecast Lockport NY: Why Today’s Snow Isn’t Just Hype

What the Photos Don't Show You

The most common misconception is that the ash was like "snow." It wasn't. Mount st helens eruption photos can't convey the texture. It was pulverized rock. It was heavy, it smelled like sulfur, and it was abrasive enough to ruin a car engine in minutes.

The photos also struggle to capture the scale. When you see a shot of a "mudflow" (a lahar), it looks like a dirty river. In reality, those flows were carrying entire houses and logging trucks like they were toothpicks.

Actionable Steps for Historians and Hobbyists

- Check the metadata: If you find a photo online, check if it’s attributed to the USGS or a private citizen. Private photos (like the Rosenquist sequence) are often protected by copyright, while government photos are usually public domain.

- Verify the Date: Many "eruption" photos are actually from the smaller steam ventings that happened in March and April 1980. The May 18 photos are distinct because the top 1,300 feet of the mountain are missing.

- Visit the Johnston Ridge Observatory: If you're in Washington, go there. They have the original cameras and high-res prints on display. Seeing the dented, ash-caked Nikons in person puts the "human" cost of these photos into perspective.

- Use Search Filters: When searching for these images, use the "Large" size filter in Google Images and look for .gov or .edu domains to ensure you aren't getting a low-quality repost or an AI-generated recreation.

The reality is that these photos aren't just cool pictures of a volcano. They are forensic evidence. Every frame told the scientists something new about how mountains die and how they are reborn.

If you want to dive deeper into the technical side, you should look up the USGS Professional Paper 1250. It’s a massive document, but it includes the most precise breakdown of the eruption sequence ever published, using these very photographs as the primary evidence.

Don't just look at the explosion; look at the "before" shots of Spirit Lake and compare them to the "after." The transformation of that landscape is arguably the most dramatic part of the whole story.