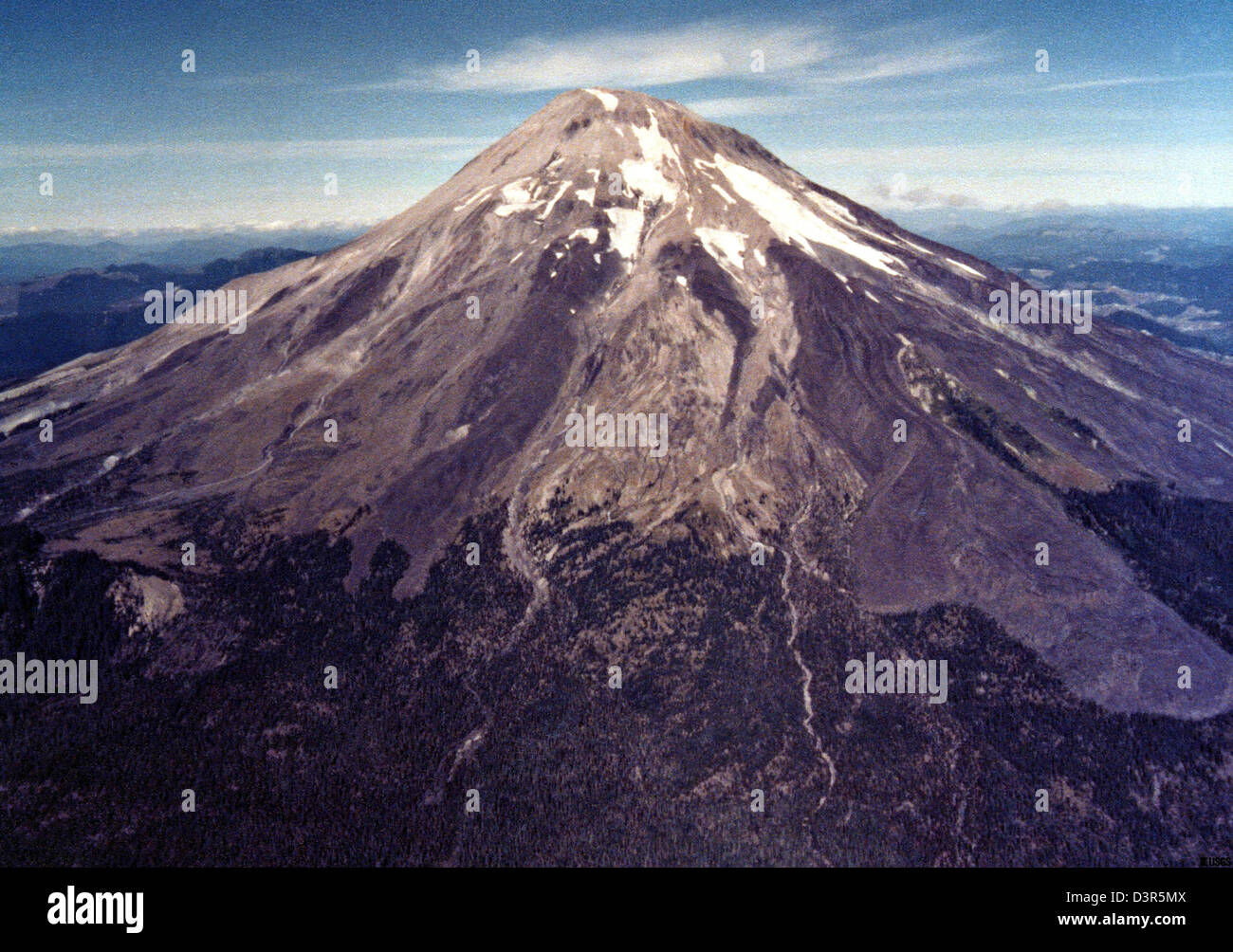

It’s hard to wrap your head around the fact that Mount St. Helens used to be the "pretty" one. If you look at photos of the Cascade Range from the 1970s, the peak didn't look like the jagged, hollowed-out crater we see today. Not even close. It was a near-perfect cone. It was symmetrical. People actually called it the "Fujiyama of America" because it looked so much like Japan’s famous Mount Fuji.

Then May 18, 1980, happened.

But focusing only on the blast is a mistake. To understand why that day was such a gut-punch to the Pacific Northwest, you have to understand what Mount St. Helens before eruption actually felt like. It wasn't just a volcano. It was a playground. It was a massive, snow-capped landmark that stood 9,677 feet tall, dominating the skyline of southwest Washington.

The Mount St. Helens Before Eruption Magic

Spirit Lake was the heart of it all. Honestly, if you talk to anyone who grew up in the area in the 50s or 60s, they’ll get misty-eyed talking about that water. It was crystal clear. I’m talking "see the bottom through thirty feet of water" clear.

The lake sat right at the foot of the mountain. Because the peak was so symmetrical, the reflection in the water on a still morning was basically a Rorschach test of alpine perfection. There were scout camps. There were lodges. Harmony Falls and the YMCA camp were staples of summer for thousands of kids.

It was an old-growth paradise. We’re talking Douglas firs and Western hemlocks that had been standing for hundreds of years, creating a canopy so thick it felt like another world.

Life at the Timberline

The lodge culture was huge. Harry R. Truman—the guy who eventually became a folk hero for refusing to leave—ran the Spirit Lake Lodge. He’d been there since the 1920s. To him, the mountain wasn't a threat; it was a neighbor. He had his pink gin, his 16 cats, and a front-row seat to the most beautiful view in the state.

People didn't go there to see a volcano. They went to fish for rainbow trout. They went to hike the lush trails that wound through huckleberry bushes. The mountain was considered "dormant," a sleeping giant that hadn't really made a peep since the mid-1800s.

👉 See also: Finding the Persian Gulf on a Map: Why This Blue Crescent Matters More Than You Think

Why Everyone Thought It Was Safe

Geologically speaking, 123 years is a blink of an eye. But for humans? That’s forever.

The last time the mountain had been active was roughly 1857. By the 1970s, the collective memory of its power had faded. It was just a backdrop. Scientists like Dwight Crandell and Donal Mullineaux from the USGS had actually published a report in 1978 warning that Mount St. Helens was the most likely volcano in the lower 48 to erupt, possibly before the end of the century.

Nobody really panicked.

It's weird to think about now, but the hubris was real. We thought we had it figured out. Even when the earthquakes started in March 1980, the general vibe was one of curiosity, not terror. Tourists actually flocked toward the mountain with "Volcano Watcher" t-shirts and binoculars.

The Bulge That Changed Everything

By April, the mountain started physically changing. This is the part of the Mount St. Helens before eruption timeline that gets truly eerie. A "bulge" began to grow on the north face.

It wasn't subtle.

The mountain was literally deforming. Magma was pushing up, but it wasn't coming out of the top. It was getting stuck in the side. This "cryptodome" was growing at a rate of about five feet per day. Think about that. A massive rock wall moving five feet every single day. By early May, the north flank had pushed outward by more than 450 feet.

✨ Don't miss: El Cristo de la Habana: Why This Giant Statue is More Than Just a Cuban Landmark

The symmetrical "Fuji" look was gone. The mountain looked bloated. Deformed. It was like a pressure cooker with a faulty lid, and everyone was just waiting for the whistle.

The Final Days of the Old Peak

The tension in May 1980 was thick. You had the "Red Zone" and the "Blue Zone" set up by Governor Dixy Lee Ray. Locals were annoyed. They wanted to get to their cabins. They wanted to check on their property.

David Johnston, a young USGS volcanologist, was stationed at Coldwater II, a ridge about six miles from the summit. He was one of the few who truly grasped the scale of what was coming, though even he couldn't have predicted the lateral blast. His presence there—and his final radio transmission—became the stuff of legend.

But on May 17, the day before the world ended, it was a beautiful Saturday.

The sun was out. A few lucky (or unlucky) residents were escorted into the restricted zone to grab belongings from their summer homes. They saw a mountain that was cracking and steaming, but still standing. Spirit Lake was still blue. The trees were still green.

Comparing the Then and Now

If you stand at the Johnston Ridge Observatory today, the scale of the loss is staggering.

- Elevation: The mountain lost 1,314 feet of its summit in seconds.

- The Lake: Spirit Lake's surface rose by 200 feet and was instantly covered in a thick "log mat" of pulverized trees that is still there today.

- The Landscape: The lush green was replaced by a grey, lunar landscape of pumice and ash.

It wasn't just a geological event. It was a total erasure of a specific kind of Pacific Northwest lifestyle. The cabins, the docks, the pristine hiking trails—they didn't just get damaged. They ceased to exist.

🔗 Read more: Doylestown things to do that aren't just the Mercer Museum

What We Get Wrong About the Pre-Eruption Era

A lot of people think the mountain gave no warning. That's a myth. It gave two months of constant shaking and steam venting.

Another misconception is that it was always a "dangerous" looking place. It wasn't. It was the ultimate weekend getaway. It was approachable. Unlike the rugged, craggy peaks of Mount Rainier or Mount Baker, St. Helens had a softness to it because of that smooth, volcanic cone shape.

Honestly, the Mount St. Helens before eruption period represents a lost era of American wilderness. It was a time before high-tech monitoring, before we realized just how violent our "scenery" could actually be.

Moving Toward a Better Understanding

If you're planning to visit the monument or just want to dive deeper into the history, don't just look at the blast photos.

Start by looking at the archival footage from the 1930s and 40s. Look at the postcards of the Spirit Lake Lodge. It gives you a sense of the scale of the "sector collapse." When the north side of the mountain failed, it wasn't just rock moving; it was the entire ecosystem of the Toutle River valley being reshaped in minutes.

Actionable Steps for History Buffs and Travelers

- Visit the Pine Creek Area: While the north side (Johnston Ridge) shows the destruction, the south side of the mountain still retains some of that pre-1980 "old growth" feel. It’s the best way to visualize what the whole mountain used to look like.

- Check the USGS Photographic Library: They have high-resolution scans of the mountain from the 1970s. Compare the "Bulge" photos from early May 1980 to the photos from 1975 to see the terrifying deformation of the rock.

- Read "Skywalker": For a real human look at the mountain before it blew, look into the accounts of the hikers who frequented the Loowit Trail before it was obliterated.

- Respect the Current Closures: As of 2026, many roads around the blast zone are still subject to washouts and landslide repairs. Always check the Gifford Pinchot National Forest alerts before heading out.

The mountain is building itself back up now. A new lava dome is growing. One day, thousands of years from now, it might be a perfect, symmetrical cone again. But for those who saw it before 1980, there will never be another Spirit Lake quite like the one Harry Truman refused to leave.

Source References:

- USGS (United States Geological Survey) Historical Archives.

- "Eruption: The Untold Story of Mount St. Helens" by Steve Olson.

- Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument Visitor Records.

- University of Washington Digital Collections (Pacific Northwest Photographs).