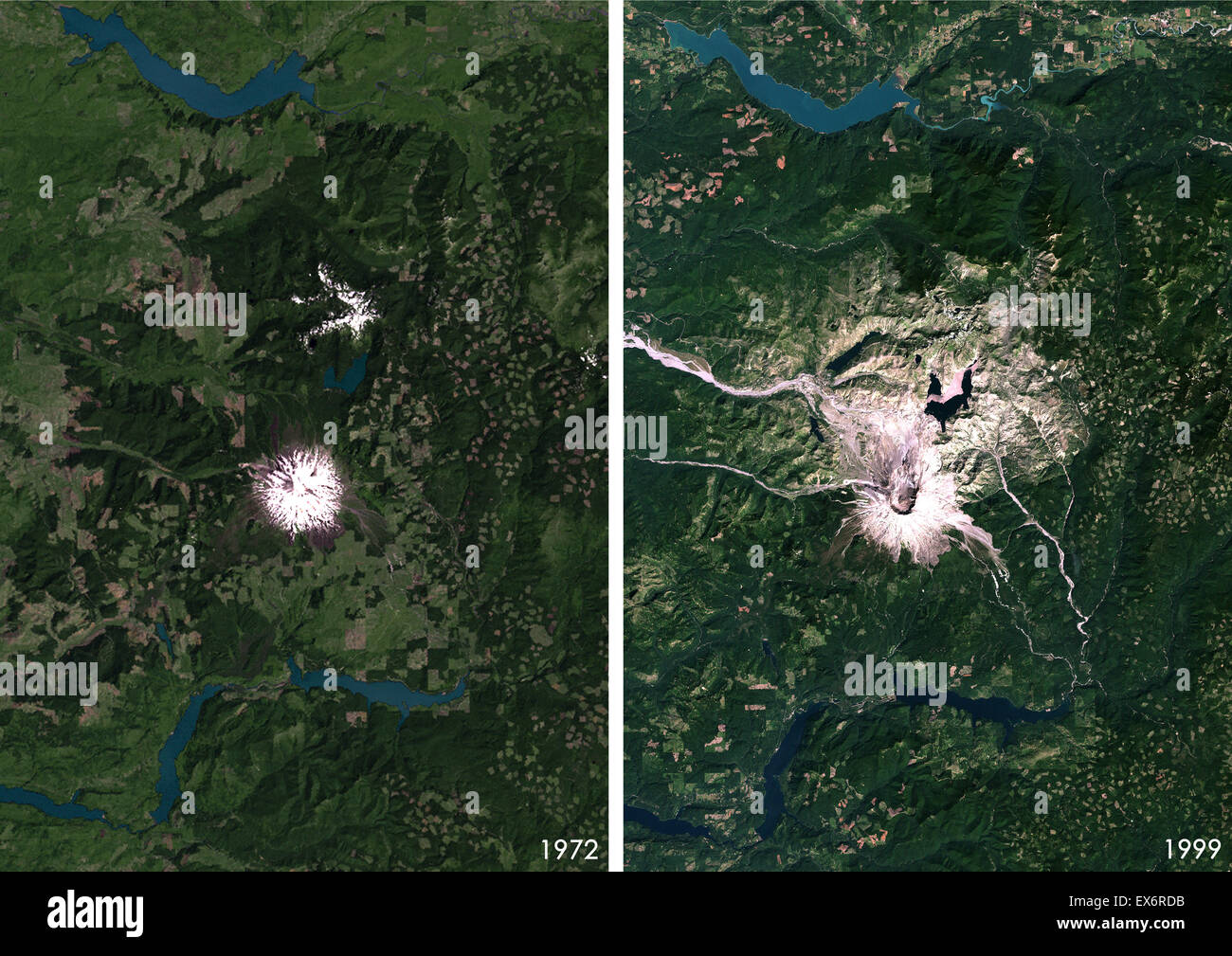

You’ve probably seen the photos. That perfect, snow-capped cone that looked more like a postcard from the Swiss Alps than a ticking time bomb in Washington State. They called it the "Mount Fuji of America." Honestly, looking at Mount St. Helens before and after the eruption is a lesson in how quickly the earth can just... decide to change the map.

On May 18, 1980, the top 1,300 feet of that mountain didn't just melt. It vanished.

Basically, the world watched a mountain turn into a crater in less than a minute. If you were standing there today, you wouldn't see the symmetry everyone raved about in the 70s. You’d see a jagged, horseshoe-shaped amphitheater that looks like a giant took a bite out of the horizon. It’s haunting. It’s also one of the most misunderstood events in American history.

The Sleeping Beauty Before the Blast

Before 1980, Mount St. Helens was a hiker's dream. It was the fifth-highest peak in Washington, sitting pretty at 9,677 feet. Spirit Lake sat at its base, crystal clear and famous for its reflections of the peak. People spent their summers there. They camped, they fished for trout, and they ignored the fact that the mountain was technically a "young" and restless volcano.

It had been quiet since 1857.

By the time the spring of 1980 rolled around, the mountain started acting up. A magnitude 4.2 earthquake hit on March 20th. Then came the steam vents. But the weirdest part? The "Bulge."

Magma was pushing into the north flank of the mountain, but it wasn't coming out. Instead, it was inflating the side of the volcano like a balloon. By early May, the north face was growing outward at a staggering five feet per day. Think about that. A mountain face moving as fast as a person walks in a few hours. Scientists like David Johnston were stationed at observation posts, watching this literal swelling. Johnston was at "Coldwater II," about six miles away. He knew it was dangerous, but nobody predicted a sideways blast.

The Moment Everything Changed

At 8:32 a.m. on Sunday, May 18, a 5.1 earthquake shook the ground. The Bulge didn't just crack; it slid. It became the largest debris avalanche in recorded history.

With the weight of the mountain suddenly gone, the pressurized magma underneath did exactly what a shaken soda bottle does when you rip the cap off. It exploded sideways. This "lateral blast" traveled at 300 miles per hour. It didn't just knock trees over; it stripped the bark off them and then flattened 230 square miles of old-growth forest.

57 people died.

Most of them weren't even in the "danger zone." Of the 57 victims, only six were inside the restricted area. People like the legendary Harry R. Truman—the 83-year-old lodge owner who refused to leave his home at Spirit Lake—became symbols of the tragedy. He, along with his 16 cats, was buried under hundreds of feet of debris. David Johnston’s last words over the radio were, "Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!" He was never found.

The Aftermath: A Gray Moonscape

If you flew over the area the next day, you wouldn't have recognized it. Everything was gray. Ash was everywhere. It wasn't like wood ash from a fireplace; volcanic ash is actually pulverized rock and glass. It's heavy, it’s abrasive, and it kills car engines instantly.

The stats are kind of hard to wrap your head around:

- The summit dropped from 9,677 feet to 8,363 feet.

- 540 million tons of ash fell over 22,000 square miles.

- Spirit Lake was raised by 200 feet and turned into a black, steaming soup of logs and volcanic debris.

- The energy released was roughly equivalent to 1,600 Hiroshima-sized atomic bombs.

For years, people thought the area was dead forever. It looked like the moon. No birds, no trees, just silence and heat.

Nature’s Weird Way of Coming Back

Here is where the "after" gets interesting. Life didn't wait for permission.

Scientists were shocked to find that pocket gophers survived because they were underground. Their tunneling actually helped mix the rich volcanic ash with the old soil, acting like tiny, furry gardeners. Then there was the prairie lupine. This purple flower was the first to pop up in the middle of the "pumice plain." It’s a nitrogen-fixer, meaning it could grow in the nutrient-poor ash and prepare the ground for everything else.

📖 Related: Dream Hotel Miami Beach: What Most Travelers Get Wrong About This Collins Ave Icon

Today, if you visit, it's green. Sorta.

It’s not the old-growth forest it used to be. It’s a "mosaic" of life. You’ve got elk herds roaming through standing dead trees—the "ghost forest." You’ve got mountain goats (whose populations have actually soared recently) climbing the crater walls. Spirit Lake is still covered in a massive "log mat" of thousands of trees that were blown into the water 46 years ago. They just float there, moving with the wind.

Why Mount St. Helens Still Matters

We learned more about volcanoes from this one event than almost any other in history. It changed how we monitor the "Ring of Fire." We now know to look for those lateral blasts. We have the Cascades Volcano Observatory because of what happened here.

If you’re planning to visit, don't expect a pristine park. Expect a monument to change. The Johnston Ridge Observatory (named after David) gives you the best view of the "throat" of the volcano.

Actionable Insights for your Visit:

- Check the status: The main access road (State Route 504) sometimes has closures due to landslides—the mountain is still settling, literally.

- Don't just look at the mountain: Walk the Hummocks Trail. Those "humps" in the ground are actually giant chunks of the mountain's former summit that landed there during the landslide.

- Respect the ash: If you're hiking, bring plenty of water. The pumice and ash reflect heat, making the "Pumice Plain" feel way hotter than the surrounding woods.

- Look for the "Log Mat": Head to the Spirit Lake overlook. Seeing those thousands of logs still floating 40+ years later is the best way to understand the sheer scale of the blast.

The mountain is quiet right now. But it's not done. It's a stratovolcano; they build themselves up and then they blow themselves apart. We’re just living in the "after" part of the cycle until the "before" starts all over again.