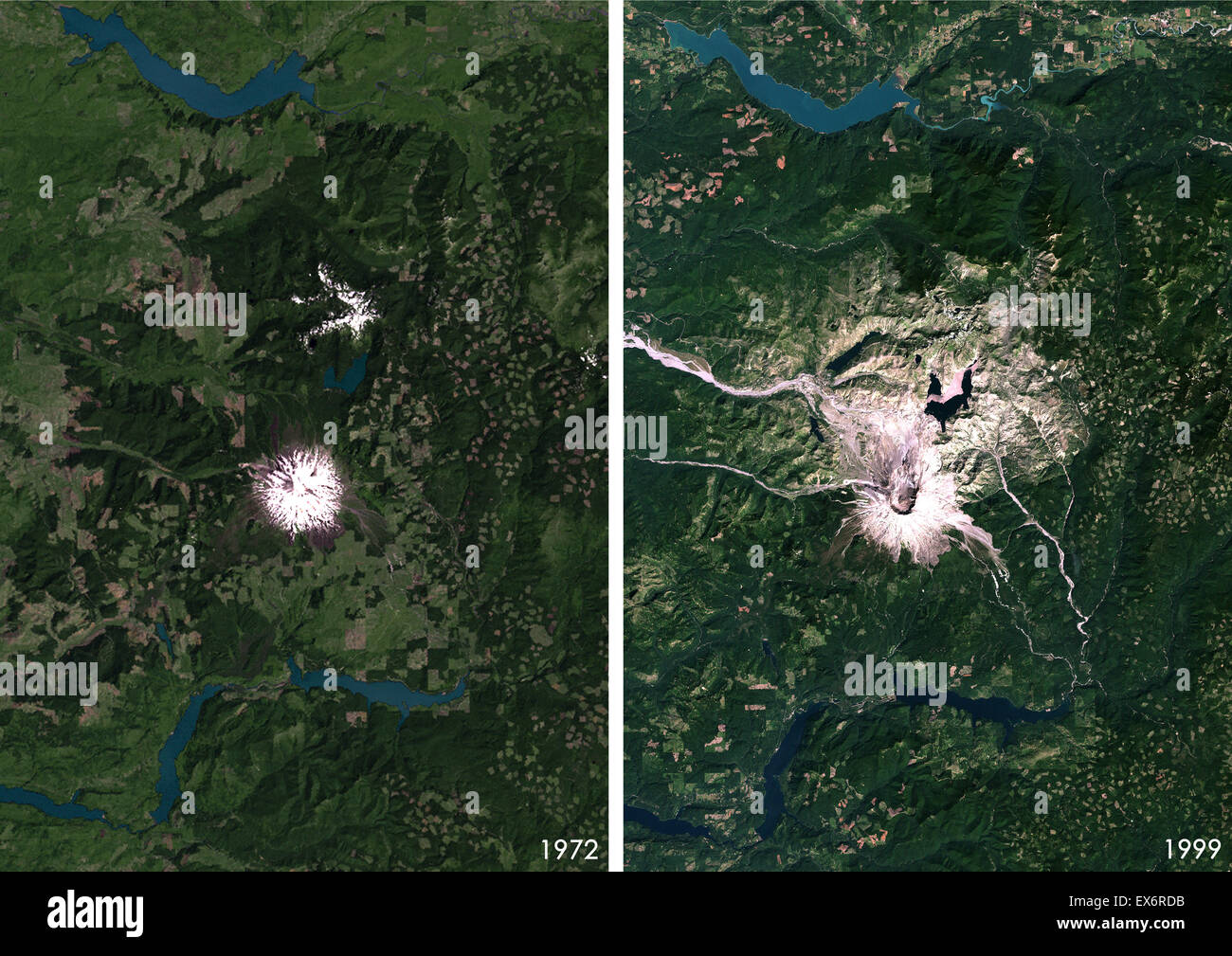

If you look at a photo of Mount St. Helens today, it looks like a giant, hollowed-out tooth. It’s rugged. It’s gray. It’s spectacular in a "desolation" kind of way. But if you’d stood on the shores of Spirit Lake in the spring of 1980, you would have seen something entirely different. You’d have seen the "Fuji of America." A near-perfect, snow-capped cone that reflected symmetrically in the water. It was postcard-perfect. Honestly, it was one of the most beautiful spots in the Pacific Northwest. Then, in a matter of seconds, it wasn't. Understanding Mount St. Helens before and after eruption isn't just about looking at two different shapes of a mountain; it’s about a total ecological and geological reset that flipped the script on everything we thought we knew about volcanoes.

The contrast is jarring. Before May 18, 1980, the peak stood at $9,677$ feet. After the blast? It dropped to $8,363$ feet. Think about that. Over $1,300$ feet of mountain simply vanished. It didn't just melt or crumble; it pulverized and traveled across the state at speeds that defy logic.

The Sleeping Beauty Before the Chaos

People forget that Mount St. Helens was a massive tourist draw long before it became a cautionary tale. It was the centerpiece of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. You had old-growth forests—hemlock, Douglas fir, and cedar—that had been standing for hundreds of years. These trees were massive. They created a deep, dark canopy where the air always felt damp and smelled like pine needles and wet earth.

Spirit Lake was the heart of it all. It was a pristine mountain lake, home to the famous Harmony Falls and a scout camp. Harry R. Truman, the 83-year-old owner of the Mount St. Helens Lodge, became a folk hero because he refused to leave. He’d lived there for over 50 years. To him, the mountain was a friend that wouldn't betray him. He was wrong, of course. But his stubbornness captured the vibe of the era: people just couldn't imagine a mountain that had been "dormant" since the mid-1800s suddenly deleting itself from the map.

The geological community knew better, though. USGS scientists like David Johnston were literally camping on ridges just miles away, monitoring a massive "bulge" on the north face. This wasn't a subtle change. The mountain was growing by five feet a day. The pressure inside was immense. Imagine a shaken soda bottle, but the bottle is made of granite and the soda is $2,000°F$ molten rock.

The Moment Everything Changed

At 8:32 a.m. on Sunday, May 18, a magnitude 5.1 earthquake struck. This was the trigger. The entire north face of the mountain—the "bulge"—didn't just slide; it failed. It was the largest terrestrial landslide in recorded history.

Because the weight of the rock was suddenly gone, the volcano "uncorked." The eruption didn't go up like a typical volcano; it went sideways. This lateral blast moved at $300$ miles per hour. It caught everyone off guard. If you were within eight miles of that blast, you didn't have a chance. The heat was enough to instantly vaporize the water in the trees, causing them to explode.

David Johnston’s final words over the radio were, "Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!" He was at an observation post six miles away. He was never found.

What the Landscape Looked Like Five Minutes Later

In less time than it takes to brew a pot of coffee, $230$ square miles of forest were wiped out. It looked like a moonscape.

The "After" was unrecognizable. The lush green was replaced by a uniform, suffocating gray. Ash fell like snow, but it wasn't cold. It was gritty, heavy, and smelled like sulfur. In some places, the ash was several feet deep. It clogged engines, killed crops in Eastern Washington, and turned day into night as far away as Spokane.

Mount St. Helens Before and After Eruption: The Ecological Shock

The transformation of Spirit Lake is probably the most haunting part of the Mount St. Helens before and after eruption story. Before, it was a deep blue jewel. After the blast, it was a black, steaming cauldron filled with a "log mat" of millions of downed trees.

The landslide actually hit the lake first, pushing the water out in a giant wave that stripped the surrounding hillsides of trees and soil, then sucked it all back into the lake basin. The lake level rose by $200$ feet. For years, scientists thought the lake was dead. It was a toxic soup of volcanic chemicals and rotting organic matter. There was zero oxygen in the water.

But then, life did something weird.

Bacteria started blooming. Specifically, Legionella—the stuff that causes Legionnaires' disease—thrived in the warm, stagnant water. It was a literal hellscape. Yet, only a few years later, life began to crawl back.

The Return of the "Pioneers"

We often think of nature as fragile. Mount St. Helens proves it’s actually incredibly aggressive. The first thing to come back wasn't a tree. It was a prairie lupine. This purple wildflower has a special trick: it can "fix" nitrogen. It didn't need fertile soil because there wasn't any. It created its own.

💡 You might also like: National Car Rental Portland Maine: How to Actually Save Time at PWM

Then came the pocket gophers. Because they lived underground, many survived the initial heat. As they tunneled through the ash, they brought up old soil and seeds from "Before," basically acting as tiny, furry gardeners that jump-started the "After."

Today, if you visit, the blast zone is a patchwork of colors. You see bright green shrubs, young alder trees, and wild strawberries. But the skeletons of the old world are still there. "Ghost forests" of silver, barkless logs still lay scattered across the ridges, all pointing away from the crater like compass needles. They show exactly which way the wind of the blast blew.

The Human Cost and the "New" Mountain

We lost 57 people that day. Most weren't even in the "Red Zone" that the government had closed off. They were in areas deemed safe. That’s the scary thing about the Mount St. Helens before and after eruption comparison—the "safe" zones of the past mean nothing to a mountain that decides to rewrite the geography.

The crater is now home to one of the youngest glaciers on Earth. While glaciers everywhere else are shrinking due to climate change, the "Crater Glacier" inside Mount St. Helens is actually growing. The massive crater walls shade the ice, and the porous volcanic rock insulates it. It’s a strange paradox: a place created by extreme heat is now one of the only places where ice is winning.

The mountain is also significantly shorter. When you stand at Johnston Ridge Observatory, you aren't looking at a mountain peak; you are looking into its guts. You can see the lava dome pulsing. It’s still an active volcano. It’s not "done." It erupted again fairly recently, between 2004 and 2008, building up more of that dome inside the horseshoe-shaped crater.

Comparing the Two Worlds

To really wrap your head around the scale, you have to look at the numbers and the physical reality.

- Topography: The summit was replaced by a 1.2-mile wide crater.

- The Toutle River: Before, it was a clear salmon stream. After, it was a massive mudflow (lahar) with the consistency of wet concrete that carried houses and bridges 30 miles downstream.

- Spirit Lake: From a recreational paradise to a protected scientific laboratory where you can still see the log mat floating on the surface four decades later.

- Forestry: Hundreds of millions of board feet of timber were lost. Some was salvaged, but much of it remains as a monument to the power of the lateral blast.

People often ask if the mountain will ever look like it did before. The short answer? No. Not in our lifetime, and probably not for thousands of years. The "Fuji" shape was the result of thousands of years of layered eruptions. The 1980 event was a "reset" button.

Actionable Insights for Your Visit

If you're planning to see the Mount St. Helens before and after eruption contrast for yourself, don't just drive to the viewpoint and leave. You need to feel the scale.

- Check the Johnston Ridge Observatory schedule: It’s the closest you can get to the crater without a climbing permit. The movie they show ends with the curtains opening to reveal the volcano. It’s a bit theatrical, but honestly? It hits hard.

- Hike the Hummocks Trail: These "hummocks" are actually giant chunks of the mountain's peak that landed miles away during the landslide. You are literally walking through the former summit.

- Look for the "Lupine" effect: If you go in early summer, look for those purple flowers. They are the reason the forest is coming back.

- Respect the "Logs": When you see the logs in Spirit Lake, remember they’ve been floating there since 1980. They move with the wind. It’s a living graveyard.

- Check road conditions: Spirit Lake Memorial Highway (WA-504) often has washouts or snow closures. Always check the WSDOT site before heading up.

The transition from the before to the after is a reminder that the ground beneath us isn't as solid as we like to think. Mount St. Helens is a living laboratory. It’s messy, it’s gray, and it’s arguably much more interesting now than it ever was as a perfect, snowy cone. It’s a story of resilience, showing that even when a mountain explodes, life finds a way to crawl out of the ash.

To get the most out of a trip to the monument, start your journey at the Mount St. Helens Visitor Center at Silver Lake to see the "Before" exhibits, then drive the 52 miles to Johnston Ridge to witness the "After." This progression provides the necessary context to understand why this landscape remains one of the most studied places on the planet.