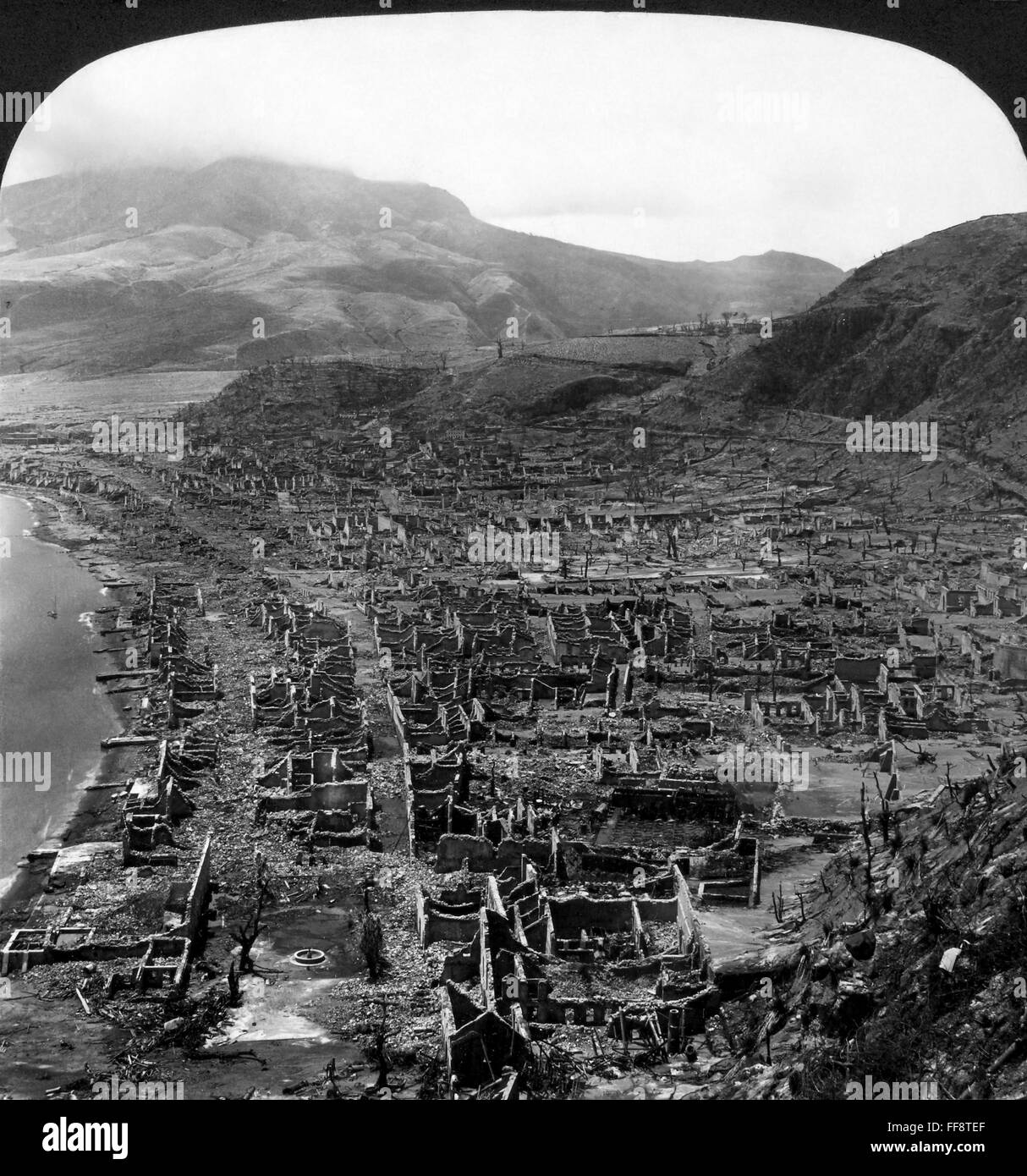

Honestly, if you look at a map of the Caribbean today, Saint-Pierre looks like a sleepy, beautiful seaside town where you can grab a great espresso and watch the sunset. But in early 1902, it was "the Paris of the West Indies." It had a theater that seated 800 people, a botanical garden, and a level of sophistication that made other colonial outposts look like backwater villages. Then, in a matter of minutes on the morning of May 8, every single bit of that prestige was erased. Mount Pelée Martinique 1902 isn't just a date in a history book; it’s the moment humanity realized we had absolutely no idea how volcanoes actually worked.

It’s a terrifying story.

Around 7:52 AM, the mountain basically unzipped. It didn't just blow its top like a stereotypical volcano in a cartoon. Instead, a massive, superheated cloud of gas and ash—what we now call a nuée ardente or pyroclastic flow—shot out of the side of the volcano and raced toward the city at over 100 miles per hour. It was moving too fast to outrun. Temperatures inside that cloud were likely over $1,000°C$. In less than three minutes, 30,000 people were dead.

Why Nobody Left Saint-Pierre

You’d think people would have run for the hills. The volcano had been steaming and coughing up ash for weeks. In late April, hikers found the Etang Sec crater lake was boiling. By early May, the town was covered in a fine grey dust that made it hard to breathe. Animals were dying. Snakes—thousands of them, including the deadly fer-de-lance—fled the slopes and crawled into the city streets, reportedly killing dozens of people and pets. It was like a scene out of a horror movie.

So why did they stay?

Politics. It’s always politics, isn't it? There was an election scheduled for May 11, and the local governor, Louis Mouttet, didn't want the progressive party to win. He needed his conservative base to stay in the city to vote. He basically downplayed the danger, sent in troops to prevent people from leaving, and even commissioned a "scientific" report that claimed everything was fine. He and his wife ended up dying in the blast alongside the citizens they told to stay put.

Some people did try to leave, but the ships in the harbor were told they couldn't clear customs yet. It was a bureaucratic nightmare that turned into a graveyard. Only two ships, the Roddam and the Roraima, managed to survive the initial blast, though they were scorched wrecks by the time they drifted away.

The Lone Survivors: Ludger Sylbaris and the Rest

The most famous story from the Mount Pelée Martinique 1902 eruption is definitely Ludger Sylbaris. He’s often called the "only" survivor, but that’s not quite true. He was a prisoner, a bit of a troublemaker who had been thrown into a tiny, poorly ventilated stone dungeon for a drunken brawl. That cell saved his life. The heat was so intense it burned his back through the small slit in the door, but the thick walls kept him from being vaporized.

✨ Don't miss: Norwegian Airline Baggage Rules: What Most People Get Wrong

There was also Léon Compère-Léandre, a shoemaker who lived on the edge of the city. He saw the cloud coming, ran into his house, and collapsed. He woke up later, surrounded by dead bodies, and somehow managed to crawl to a nearby village despite horrific burns. And then there was Havivra Da Ifrile, a young girl who supposedly hopped in a boat and hid in a sea cave.

But for a city of 30,000? That's it. A prisoner, a shoemaker, and a little girl.

The Science That Emerged from the Ash

Before 1902, volcanology was barely a science. People thought volcanoes just leaked lava like a tipped-over pot of soup. The Mount Pelée Martinique 1902 event forced a massive shift in how we understand the Earth.

Alfred Lacroix, a French mineralogist, arrived on the island shortly after the disaster. He spent months documenting what he saw, and he was the one who coined the term nuée ardente (glowing cloud). He realized that the real danger wasn't always the lava you can see crawling down a hill; it was the invisible, heavy-than-air gases and pulverized rock that behave like a fluid.

What is a Peléan Eruption?

Because of this event, we now categorize a specific type of volcanic activity as a "Peléan eruption." It’s characterized by:

- Extremely viscous (thick) magma.

- The formation of a "spine" or dome in the crater.

- Explosive outbursts that create those deadly pyroclastic flows.

The "Spine of Pelée" was actually one of the most bizarre sights after the eruption. A massive needle of solid lava was pushed up out of the crater like a piston. At its peak, it was twice as high as the Washington Monument. It stood there for months, a jagged, terrifying monument to the disaster, before it eventually crumbled.

Visiting Saint-Pierre Today

If you go to Martinique now, you can still see the scars. It’s a bit haunting. The ruins of the old theater are still there—you can walk up the stairs where people once wore their finest silks to see French plays. The dungeon where Sylbaris survived is a major tourist stop.

📖 Related: Air Passes American Airlines: The $250,000 Mistake That Changed Travel History

The volcano itself, Mount Pelée, is still active. It’s monitored constantly now by the Observatoire Volcanologique et Sismologique de Martinique (OVSM). Scientists use GPS, seismometers, and gas analysis to make sure nothing like 1902 ever happens again. But it’s a reminder that nature doesn't care about our elections or our beautiful cities.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Traveler or History Buff

If you’re planning to visit the site of the Mount Pelée Martinique 1902 disaster, keep these things in mind to get the most out of the experience:

- Check the VSI: Before hiking Pelée, check the Volcanic Alert Level. It’s usually at "Green" (Normal), but the mountain is alive.

- Visit the Musée Franck Perret: This is the volcanological museum in Saint-Pierre. It houses twisted bits of metal, melted clocks frozen at 7:52, and everyday objects that were turned into charred relics in seconds. It’s small but heavy.

- Hike the Aileron Trail: If you want to see the crater, this is the most popular route. Just be prepared for the weather to change in seconds. One minute it's sunny; the next, you're in a thick cloud.

- The Underwater Ruins: For divers, the bay of Saint-Pierre is one of the best wreck-diving spots in the world. You can see the remains of the ships that were swamped by the ash cloud, now covered in coral and home to tropical fish.

Understanding the tragedy of 1902 changes how you see the Caribbean. It’s not just white sand and palm trees; it’s a landscape shaped by some of the most violent forces on the planet. The people of Martinique rebuilt, but the ghost of the "Paris of the West Indies" is still very much present in the quiet ruins along the shore.

To dig deeper into the actual eyewitness accounts from the ships in the harbor, look for the digitized archives of the New York Times or the London Gazette from May and June of 1902. The descriptions written by the surviving sailors are far more visceral than any modern textbook can capture. They describe the sea boiling and the sky turning into a solid wall of fire. It’s a sobering reminder of why we respect the mountain today.