Mount Etna is basically the heartbeat of Sicily. If you've ever stood in the streets of Catania, you’ve felt it—that low-frequency hum or the sight of a "puff" of smoke that looks innocent but carries a heavy punch. People see headlines about a volcano eruption Mount Etna and think it’s a doomsday scenario every single time. Honestly? It’s usually just Tuesday for the locals. While the world watches dramatic TikTok clips of lava fountains, the people living on the slopes are often more worried about the wind direction and whether they’ll have to sweep black volcanic sand off their balconies for the third time this week.

It’s big. It’s loud. It’s incredibly complex.

We aren't talking about a single mountain with one hole at the top. Etna is a sprawling, multi-vented beast that covers about 460 square miles. To put that in perspective, you could fit several small European cities inside its footprint. Scientists at the Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV)—specifically the Osservatorio Etneo in Catania—spend their entire lives trying to figure out what this mountain is thinking. They use tiltmeters, gas sensors, and satellite imagery to track every burp and groan. But even with all that tech, Etna still manages to surprise everyone with its "paroxysms," which is just a fancy scientific word for a violent, sudden outburst of activity.

Why Mount Etna Doesn't Behave Like Other Volcanoes

Most people assume volcanoes work like a shaken soda bottle. Pressure builds, it pops, and then it’s over for a few years. Not here. A volcano eruption Mount Etna is unique because the plumbing system is constantly open. It’s "persistently active." This means the magma is always relatively close to the surface, bubbling away like a pot of pasta water that’s just about to boil over.

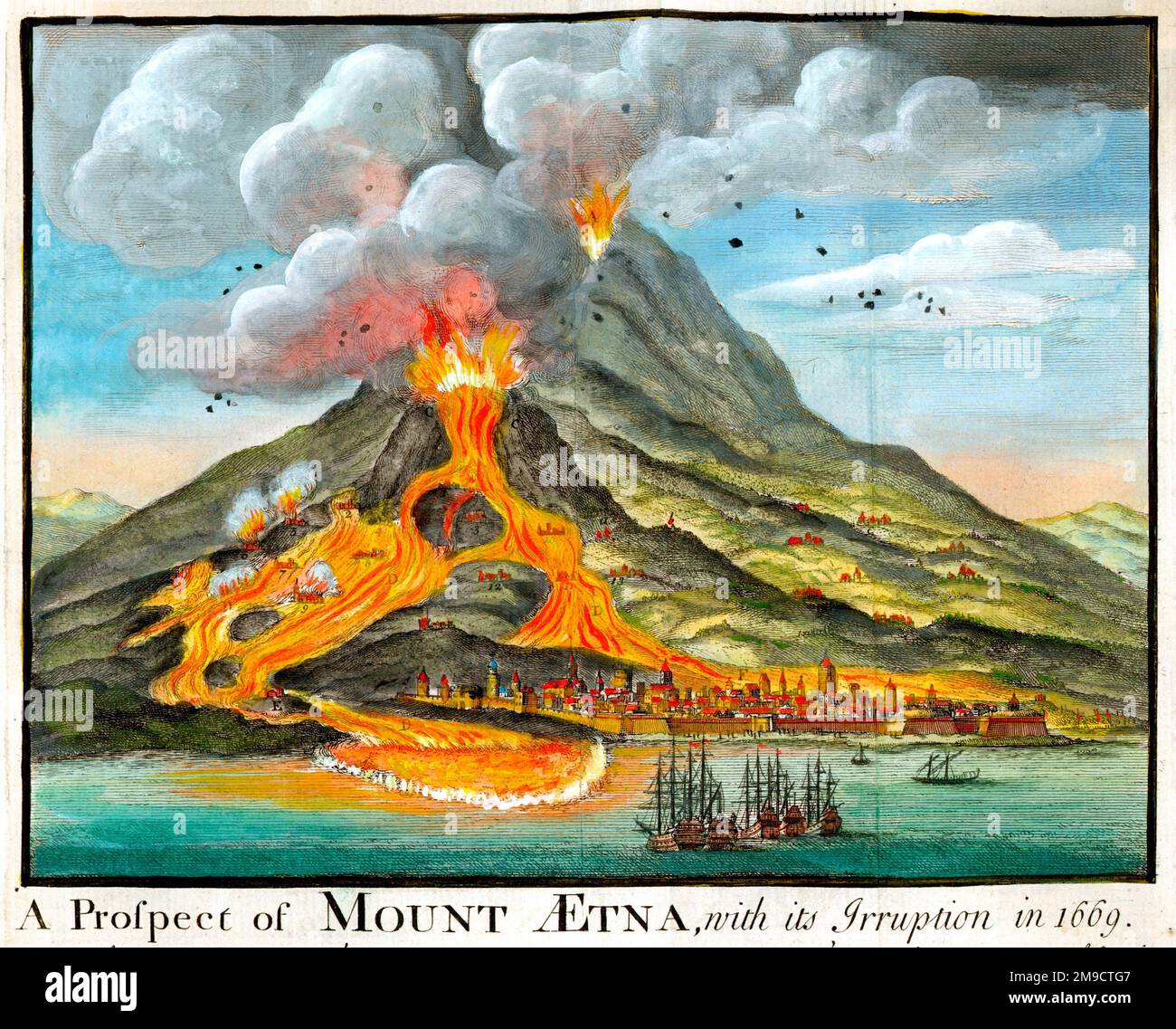

There are two main types of eruptions here. You’ve got the summit eruptions, which happen at the very top craters (Voragine, Bocca Nuova, Northeast Crater, and Southeast Crater). These are usually what you see on the news—the towering ash plumes and the glowing lava fountains known as Strombolian activity. Then you have the flank eruptions. These are the ones that actually make the locals sweat. These happen when the magma finds a weak spot on the side of the mountain and breaks through, sometimes much lower down near villages.

The 2021-2024 Activity Cycle

Between 2021 and early 2024, Etna went through an incredible phase. The Southeast Crater, which is basically the "new kid" on the mountain having only formed in the 1970s, grew hundreds of feet in height in just a few months. It became the highest point on the volcano. During this period, we saw dozens of paroxysms.

Think about a fountain of fire reaching 1,500 meters into the sky. That’s nearly a mile high.

The sound is what stays with you. It’s not a bang; it’s a rhythmic, chest-thumping thud-thud-thud that can be heard as far away as Calabria on the Italian mainland. When the wind blows toward the south, Catania’s Fontanarossa Airport has to shut down completely. Why? Because volcanic ash and jet engines are a disastrous mix. The ash is basically tiny shards of glass. If a plane flies through it, those shards melt in the high heat of the engine and turn into a ceramic coating that chokes the turbines. It’s a logistical nightmare for travelers, but a necessary safety precaution.

The Misconception of Danger

Is Etna dangerous? Yes, obviously. It’s a massive pile of molten rock. But the "danger" is often misunderstood by people who don't live there.

Historically, Etna isn't a "killer" volcano in the way Vesuvius was for Pompeii. Vesuvius is an explosive stratovolcano that produces pyroclastic flows—those fast-moving clouds of hot gas and rock that kill instantly. Etna is more of an effusive volcano. The lava generally moves slowly. You can literally walk away from it. In the 1991-1993 eruption, which lasted 473 days, the Italian authorities and even the U.S. Marines (Operation Volcano Buster) used explosives and concrete blocks to divert lava flows away from the town of Zafferana Etnea. It worked. They saved the town.

The real danger today isn't usually the lava; it’s the tephra.

Tephra is the collective term for the rocks, lapilli, and ash spat out during an eruption. If you’re hiking near the summit during a sudden burst, you’re in trouble. In 1979, a sudden explosion at the Bocca Nuova crater killed nine tourists who were just standing near the rim. This is why the local Alpine Guides and the Civil Protection agency are so strict about who gets to go where. If the sensors at the INGV start twitching, the upper elevations are closed off immediately. No exceptions.

💡 You might also like: Eleni's Greek Taverna Springfield: Why Locals Keep Coming Back

Living in the Shadow: The Volcanic Economy

You might wonder why anyone would live next to a giant that could destroy their house. The answer is in the soil. Volcanic ash is packed with minerals—phosphorus, potassium, and magnesium. This makes the land around Etna some of the most fertile on the planet.

- The Wine: Etna DOC wines are currently some of the most sought-after in the world. Nerello Mascalese grapes grown in volcanic sand produce wines that critics compare to fine Burgundy.

- The Honey: Zafferana Etnea is the "City of Honey." The bees feed on the wildflowers that are the first things to grow back after a lava flow cools.

- The Tourism: Thousands of people flock here to ski on the slopes in the winter (yes, you can ski on a volcano) and hike the craters in the summer.

But there is a psychological cost. There’s a term locals use: A Muntagna. They don't call it Etna. They call it "The Mountain," and they speak about it as if it’s a living person—specifically a mother. She gives life through fertile soil, but she can also take things away if she’s having a bad day. There’s a certain stoicism in Sicilian culture that comes directly from this relationship. You build, you grow, and if the mountain takes it, you start over.

The Scientific Mystery of the "Deep Feed"

One of the things that keeps geologists like Dr. Boris Behncke (a leading expert at INGV) busy is the source of the magma. Most volcanoes form where tectonic plates clash or pull apart. Etna is weird. It’s sitting on a complex intersection of the African and Eurasian plates, but the chemistry of its lava looks more like it’s coming from a "hotspot" deep in the mantle, similar to Hawaii.

Wait. Why is a Hawaiian-style hotspot sitting in the middle of the Mediterranean?

Scientists are still debating this. Some think the crust underneath Sicily is tearing or "windowing," allowing deep mantle material to suck upward. This complexity is why predicting a volcano eruption Mount Etna is so difficult. The mountain has multiple "plumbing" lines. Sometimes the magma comes from a shallow chamber just a few kilometers down. Other times, it comes screaming up from 30 kilometers deep with very little warning.

Practical Insights for the Modern Traveler

If you are planning to visit or are tracking the latest activity, you need to look beyond the sensationalist headlines. A "red alert" from the news might just mean there’s ash on the runway, not that the mountain is exploding.

- Check the INGV website directly. They provide real-time updates and "Communique" reports that are the gold standard for accuracy. If they say the tremor is increasing, believe them.

- Respect the altitude. The summit is over 3,300 meters (about 11,000 feet). It is cold, the air is thin, and the weather changes in seconds. Even if it's 30°C on the beach in Taormina, it could be freezing and foggy at the Sapienza Refuge.

- The "Crater Rings" are real. Etna is one of the few volcanoes on Earth that produces "volcanic vortex rings"—perfect circles of smoke that look like giant O's blown by a smoker. They are rare, beautiful, and totally harmless.

- Watch the Tremor. If you’re looking at the live seismographs, look for the "volcanic tremor." When that line starts spiking into the red, a paroxysm is usually imminent.

What’s Next for Etna?

The mountain is currently in a state of flux. After the intense activity of the early 2020s, there have been periods of relative quiet, but "quiet" for Etna still involves constant gas emissions and the occasional small explosion. The Southeast Crater remains the most likely source of future drama. Geologists are also watching the eastern flank, which is slowly sliding toward the Ionian Sea at a rate of a few centimeters per year. This "flank instability" is a long-term concern because if a massive chunk ever collapsed into the sea, it could theoretically cause a tsunami. But we are talking about a "thousands of years" timeline, not a "next week" timeline.

💡 You might also like: Royal Motel Secaucus NJ: What It’s Really Like Staying Near the Lincoln Tunnel

For now, the best way to handle the next volcano eruption Mount Etna is with a mix of respect and preparation. If you’re in the area when it happens, don't panic. Get to a safe viewing distance (like the town of Milo or the hills around Taormina), grab a glass of local Nerello Mascalese, and watch the greatest show on Earth.

Actionable Steps for Monitoring and Safety:

- Download the "Sismos" or similar seismic tracking apps that pull data from the INGV-OE feeds to see real-time tremor levels.

- If traveling, always have a "Plan B" for transportation. If the Catania airport closes, you may need to quickly pivot to Comiso Airport or take a train to Palermo.

- Never attempt to reach the summit craters without a certified Volcanological Guide; the "forbidden zone" is enforced by the authorities and is there because the ground can literally open up or collapse without warning.

- Keep a high-quality N95 mask in your bag if you are in the Etna region during an active phase. Volcanic ash is an irritant to the lungs and eyes; even if you aren't near the lava, the "black rain" of ash can be a health hazard.