History is usually written as a series of clean dates. We see a name, a year, and a title, then we move on. But being the Prime Minister of India in April 1977 wasn't a clean experience. It was chaos. It was the first time in nearly thirty years that someone not named Nehru or Gandhi sat in the big chair. Morarji Desai had just taken the oath on March 24, so by April, he was still basically figuring out where the light switches were in 1 Safdarjung Road.

The air in Delhi that April was thick. Not just with the pre-summer heat, but with a weird mix of euphoria and paranoia. The Emergency had just ended. Indira Gandhi had been routed. People were literally dancing in the streets because they could speak again without looking over their shoulders. But for Desai, the honeymoon lasted about five minutes. He wasn't just leading a country; he was managing a "khichdi" government—a patchwork quilt of ideologies that hated each other almost as much as they hated the Congress party.

Honestly, it’s a miracle the government didn't implode in those first thirty days.

The Man Who Waited Forever

Morarji Desai was 81 years old in April 1977. Think about that. Most people are decades into retirement by then, but Desai was finally grasping the prize he’d wanted since the 1960s. He was an austere, stiff-backed Gandhian. He didn't drink tea or coffee. He famously followed "Shivambu," which is a polite way of saying he drank his own urine for health reasons. This made him a bit of an enigma—or a joke—to the international press, but in India, he represented a return to "morality" after the perceived corruption of the Emergency years.

He didn't get the job easily. Even though the Janata Party won, they had to choose between Desai, Jagjivan Ram (the Dalit powerhouse who defected from Indira at the last second), and Chaudhary Charan Singh (the champion of the northern farmers). It took the intervention of elders like Jayaprakash Narayan and Acharya Kripalani to force a consensus. So, by the time April rolled around, Desai was presiding over a cabinet where his ministers were already eyeing his seat.

💡 You might also like: Brian Walshe Trial Date: What Really Happened with the Verdict

Restoring the Constitution: April’s Main Mission

The biggest thing on the plate of the Prime Minister of India in April 1977 was the literal restoration of democracy. You have to remember, Indira Gandhi had gutted the Constitution with the 42nd Amendment. She’d made the judiciary a puppet. She’d extended the life of the Lok Sabha.

Desai’s Law Minister, Shanti Bhushan, was working overtime that month. They were laying the groundwork for what would become the 43rd and 44th Amendments. They had to undo the damage. But it wasn't just about laws; it was about the vibes. Desai had to show he wasn't a dictator. He started holding press conferences. He allowed the opposition—now the bruised Congress—to actually speak on the radio. It sounds like basic stuff now, but in April 1977, it felt like breathing for the first time after being underwater.

The Messy Dismissal of State Governments

If you want to see where the "Janata experiment" started to get aggressive, look at late April 1977. The Home Minister, Charan Singh, was pushing a controversial move. He argued that since the Congress had been wiped out in the Lok Sabha elections in northern states, the Congress-led state governments in places like UP, Bihar, and Punjab had lost their "moral mandate."

Desai agreed.

📖 Related: How Old is CHRR? What People Get Wrong About the Ohio State Research Giant

On April 30, 1977, the Acting President B.D. Jatti was basically forced to sign proclamations dissolving nine state assemblies. This was a massive use of Article 356. Critics called it undemocratic. Supporters called it a "cleansing." It was the first real sign that the Janata Party could be just as ruthless as the people they replaced. It created a constitutional standoff that defined the last week of that month.

Foreign Policy and the "Genuine" Non-Alignment

While all this internal drama was happening, Desai was trying to fix India’s image abroad. Under Indira, India had tilted heavily toward the Soviet Union. In April 1977, Desai and his Foreign Minister, a certain silver-tongued orator named Atal Bihari Vajpayee, started pushing "Genuine Non-Alignment."

They wanted to balance the scales. They reached out to the United States, which had been frosty since the 1971 war. But they didn't want to dump the Soviets either. It was a delicate tightrope walk. Jimmy Carter was the US President then, and there was this brief, shining moment where it looked like the two largest democracies might actually become best friends. Desai was firm, though. He told the Americans he wouldn't sign the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) because it was discriminatory. He was old-school. He wasn't going to be bullied.

The Economic Ghost of April 1977

Inflation was a nightmare. People think the Emergency "fixed" the economy because trains ran on time, but it was a pressure cooker. When the lid came off in April, prices started creeping up. Desai, being a fiscal conservative and a former Finance Minister, wanted to cut spending.

👉 See also: The Yogurt Shop Murders Location: What Actually Stands There Today

But his cabinet was full of socialists like George Fernandes. Fernandes was the guy who later kicked Coca-Cola and IBM out of India. In April, those tensions were just starting to simmer. Desai wanted a village-centric economy. He wanted to focus on agriculture and small-scale industries. He genuinely believed that India’s soul lived in the village, not in the big steel plants Nehru loved.

Why the Janata Experiment Still Matters

People usually talk about the Janata Party as a failure because it collapsed by 1979. They fought too much. Desai and Charan Singh eventually broke the party apart. But looking at the Prime Minister of India in April 1977, you see the blueprint for every coalition government that followed.

They proved that a non-Congress government was possible. They proved that the Indian voter could punish an authoritarian leader. Even if they couldn't stay together, they did the "janitorial work" of cleaning up the constitutional mess left by the Emergency.

Actionable Insights for History Enthusiasts and Students

If you’re researching this era or trying to understand Indian politics, don't just look at the dates.

- Read the Shah Commission Reports: These were the inquiries started shortly after April 1977 to investigate Emergency excesses. They provide the raw data of what Desai was trying to "fix."

- Analyze the 44th Amendment: This is the lasting legacy of the Desai government. It made it almost impossible for any future Prime Minister to declare an internal Emergency as easily as Indira did.

- Look at the 1977 Manifesto: Compare the Janata Party's "bread and liberty" promises with their actual performance. It’s a masterclass in the difficulties of transitionary governance.

- Study the Rural Pivot: Look at the industrial policy changes initiated in late 1977. It explains a lot about why India’s liberalization was delayed until 1991—Desai’s team was moving in the opposite direction, toward decentralization.

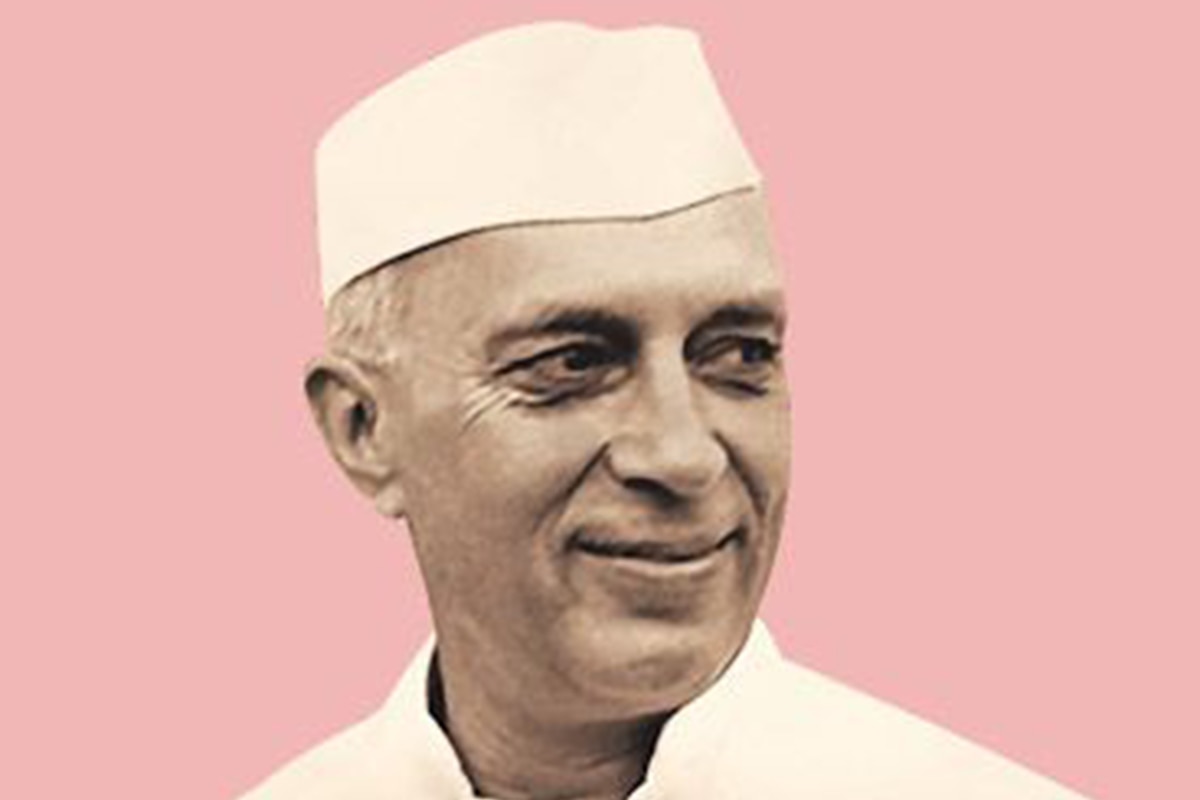

The story of April 1977 isn't just about an 81-year-old man in a white cap. It’s the story of a country trying to find its pulse again. It was loud, it was uncoordinated, and it was deeply human. Morarji Desai wasn't perfect, and his government was a circus at times, but for one month in the spring of '77, he held the door open for the democracy we recognize today.

To get a real sense of the atmosphere, track down the archives of The Statesman or The Indian Express from those specific weeks. The headlines shifted daily from "Democracy Reborn" to "Cabinet Infighting," showing just how fast the "Second Independence" met the cold wall of reality.