You’ve probably seen them on your feed—those hyper-saturated, glowing marbles floating in a velvet-black void. They look like something out of a high-budget sci-fi flick. But honestly, most moons of Jupiter images floating around the internet aren't exactly what a human eye would see if you were hitching a ride on the Juno spacecraft. Space photography is weird. It’s less about "snapping a pic" and more about data translation.

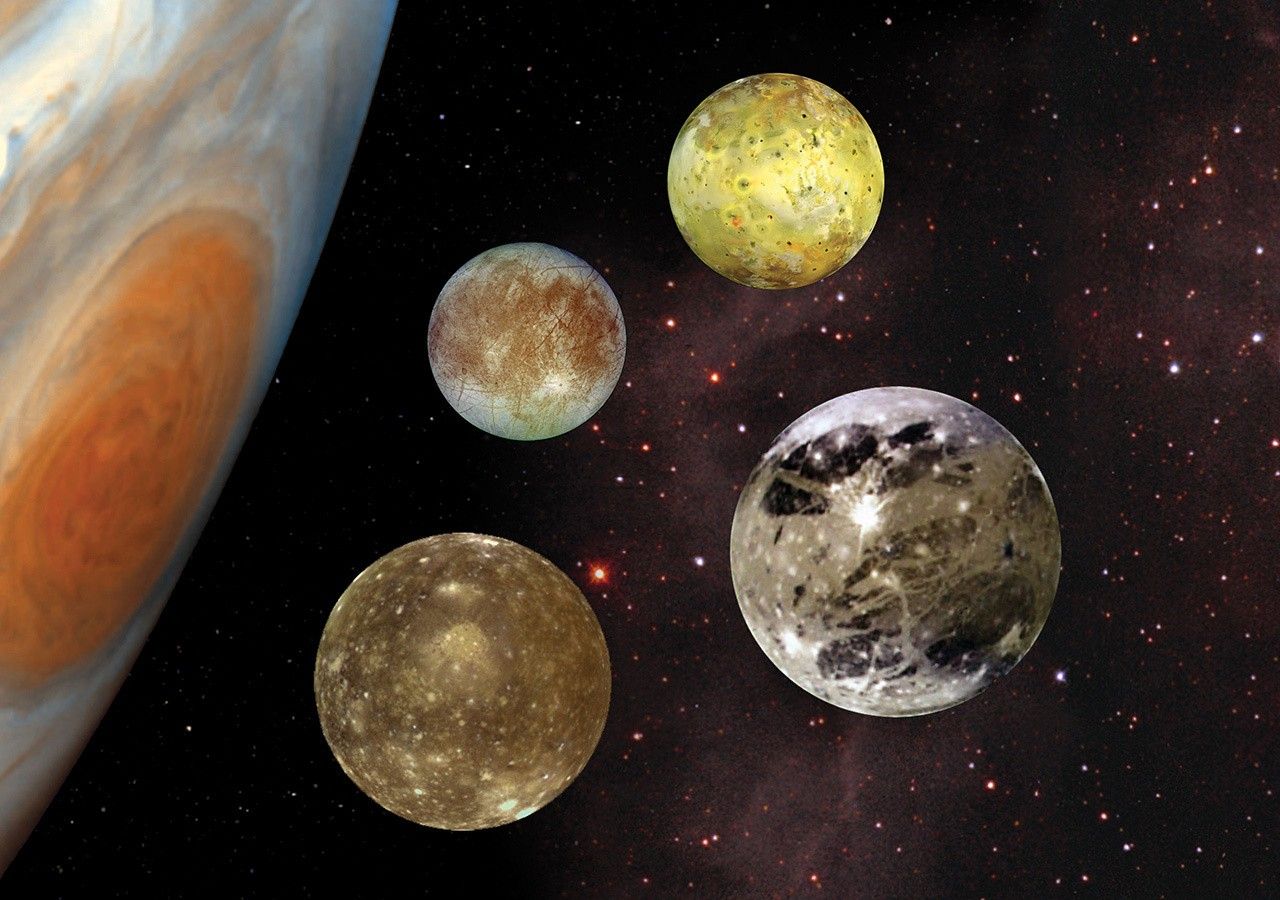

The Jovian system is a chaotic, radiation-soaked neighborhood. Taking a clear photo there is a nightmare. Yet, the imagery we have from missions like Galileo, Voyager, and now Juno, has fundamentally changed how we understand geology and the potential for life. We aren't just looking at rocks. We're looking at active volcanoes on Io and hidden oceans on Europa.

The Truth About "False Color" in Space Photography

Most people get annoyed when they find out a space photo is "false color." They feel cheated. But here’s the thing: if we only looked at "true color" images, we’d miss almost everything interesting. Jupiter’s moons are often shrouded in subtle hues that the human eye struggles to differentiate.

NASA scientists use specific filters to highlight different chemical compositions. When you see a shot of Europa where the cracks look like deep, angry red veins, that’s often an enhancement. It’s meant to show where salts and compounds are leaching out from the subterranean ocean. It’s data visualization, not a filter for the sake of "vibes." Basically, these moons of Jupiter images are maps disguised as postcards.

Io: The Pizza Moon That Refuses to Calm Down

Io is a mess. It’s the most geologically active object in the solar system, and the images we have of it prove it. It doesn’t look like a moon; it looks like a moldy pepperoni pizza. Why? Because it’s being constantly squeezed. Jupiter’s massive gravity, plus the pull from Europa and Ganymede, creates "tidal heating."

The moon literally flexes. This friction generates massive heat, leading to hundreds of volcanoes. In high-resolution shots from the JunoCam, you can see plumes of sulfur shooting miles into space. There are no impact craters on Io. Not one. The volcanoes erupt so frequently that they "pave over" the surface constantly. It’s a world that is effectively rebuilding itself every few million years. If you look at older Voyager 1 images compared to modern Juno shots, the landscape has actually shifted. That’s wild for a celestial body.

🔗 Read more: Why the Pen and Paper Emoji is Actually the Most Important Tool in Your Digital Toolbox

Europa and the Hunt for Alien Fish

If Io is fire, Europa is ice. It’s arguably the most famous moon because of what's underneath. Scientists are almost certain there’s a saltwater ocean beneath its frozen crust. When you look at moons of Jupiter images focusing on Europa, you’ll notice "chaos terrain." It looks like a jigsaw puzzle that someone broke and put back together poorly.

The "Lenticulae" or reddish spots on the surface are fascinating. They suggest that warmer ice is rising from below, melting through the colder surface. Dr. Kevin Hand at JPL has spent years arguing that these images are our best hint at a habitable environment. We’re not looking for little green men on the surface. We’re looking at the surface to see what’s happening in the dark, miles down.

Ganymede: The Giant With a Heart of Gold (Magnetism)

Ganymede is huge. It’s bigger than Mercury. It’s the only moon we know of that has its own magnetic field. When the Hubble Space Telescope captured images of Ganymede’s aurorae, it was a turning point. By watching how those aurorae rocked back and forth, researchers could tell there was a salty ocean underground.

The imagery here is less "fiery" than Io but more "ancient" than Europa. It’s a mix of dark, cratered regions and lighter, grooved terrain. It’s a record of billions of years of solar system history. You’ve got to appreciate the sheer scale. Standing on Ganymede, you’d feel like you were on a planet, not a moon.

Why JunoCam Is a Game Changer

Historically, space images were the playground of elite scientists. You waited for the press release. Juno changed that. NASA decided to put a camera on the Juno probe primarily for public outreach—the JunoCam.

💡 You might also like: robinhood swe intern interview process: What Most People Get Wrong

The raw data is uploaded to a public server. Amateur image processors—people like Kevin M. Gill or Gerald Eichstädt—take those raw "bacon strips" of data and turn them into the breathtaking moons of Jupiter images you see on Instagram. These aren't just NASA employees; they are hobbyists using sophisticated math to stitch together frames. This democratization of space imagery means we get more "artistic" views that still maintain scientific integrity.

The Difficulty of the Shot

You can't just point and shoot at Jupiter. The radiation environment is lethal to electronics. The Juno spacecraft is essentially a giant armored vault. Every time it gets close to Jupiter or its moons for a "perijove" pass, the camera is being pelted by high-energy particles. This causes "noise" in the images—static that has to be cleaned up.

Also, the speeds are insane. These probes are screaming past the moons at tens of thousands of miles per hour. Capturing a crisp, non-blurry image requires incredible precision in timing and shutter speed. It’s a miracle we have any clear photos at all.

Future Views: JUICE and Europa Clipper

We are currently in a bit of a golden age. The ESA’s JUICE (JUpiter ICy moons Explorer) and NASA’s Europa Clipper are on their way. By the early 2030s, the quality of our moons of Jupiter images is going to jump by an order of magnitude.

We’re going to see Europa’s surface with enough detail to pick out landing sites. We’ll see the vents on Ganymede. We might even see the shimmer of water vapor plumes in real-time. It’s going to move from "blurry shapes" to "topographic maps."

📖 Related: Why Everyone Is Looking for an AI Photo Editor Freedaily Download Right Now

How to Find Authentic Images Yourself

Don't just trust a random "Space_Porn" Twitter account. If you want the real deal, go to the source.

- NASA’s Planetary Data System (PDS): This is where the raw stuff lives. It’s dense and hard to navigate, but it’s the truth.

- JunoCam’s Community Page: You can vote on what the camera should take a picture of next. Seriously.

- Mission Galleries: Search specifically for "Galileo Mission Image Gallery" for the 90s-era classics or "Juno Mission Gallery" for the modern hits.

When you look at these images, look for the shadows. The height of a cliff on Io or the depth of a ridge on Europa is revealed by the slant of the sun. Those tiny details tell us the thickness of ice or the viscosity of lava. It’s not just a pretty picture; it’s a crime scene investigation of the solar system’s history.

What to Do Next

If you’re genuinely interested in exploring these worlds, don’t just scroll. Download a high-resolution "map projection" of Europa. Open it up and zoom in until you see the pixels. Try to find a spot that doesn't have a name yet.

Check out the "Eyes on the Solar System" tool by NASA. It’s a web-based sim that lets you see where these moons are right now and which spacecraft is pointing a camera at them. Seeing the context of the photo—the distance, the angle, the lighting—makes the image itself way more impactful. Stop looking at them as wallpaper and start looking at them as physical places you could, theoretically, stand on. If you didn't melt or freeze instantly, of course.