You’ve probably seen the photos of the weathered stone facade and the star-shaped window. It looks peaceful. Quiet. But honestly, Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo—or just Carmel Mission to most of us—is one of the most complicated spots in California. It isn't just a pretty backdrop for a wedding or a quick stop on a coastal road trip. It’s the final resting place of Junípero Serra, the headquarters of the entire California mission system, and a site of intense cultural friction that still resonates today.

Most people walk through the courtyard and see a relic. They’re missing the point. This place was the nerve center of the Spanish colonial project in the West. It’s where the strategy was mapped out, where the records were kept, and where the clash between European Catholicism and the indigenous Rumsen Ohlone people played out in the most intimate ways.

The Reality of the "Father Serra" Legacy

Let’s talk about Junípero Serra. You can’t mention Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo without him. He moved the mission from Monterey to the Carmel Valley in 1771 because the soil was better and, frankly, he wanted to get his neophytes away from the "immoral" influence of the Spanish soldiers at the Presidio. He lived here. He died here in 1784. His remains are right there under the floorboards in front of the altar.

For decades, the narrative was purely hagiographic. He was the "Apostle of California." Then, when Pope Francis canonized him in 2015, things got loud. Indigenous activists and historians like Elias Castillo, author of A Cross of Thorns, pointed out the devastating reality of the mission system: the suppression of native languages, the forced labor, and the catastrophic loss of life due to European diseases.

It’s a heavy vibe. You feel it when you stand in the basilica. It’s beautiful, sure. The catenary arch—the first of its kind in California—is an architectural marvel for the late 18th century. But it’s also a monument to a system that fundamentally erased a way of life. When you visit, don't just look at the statues. Look at the names. Look at the history of the Esselen and Ohlone people who actually built these walls with their own hands.

✨ Don't miss: Anderson California Explained: Why This Shasta County Hub is More Than a Pit Stop

Why the Architecture is Actually Weird

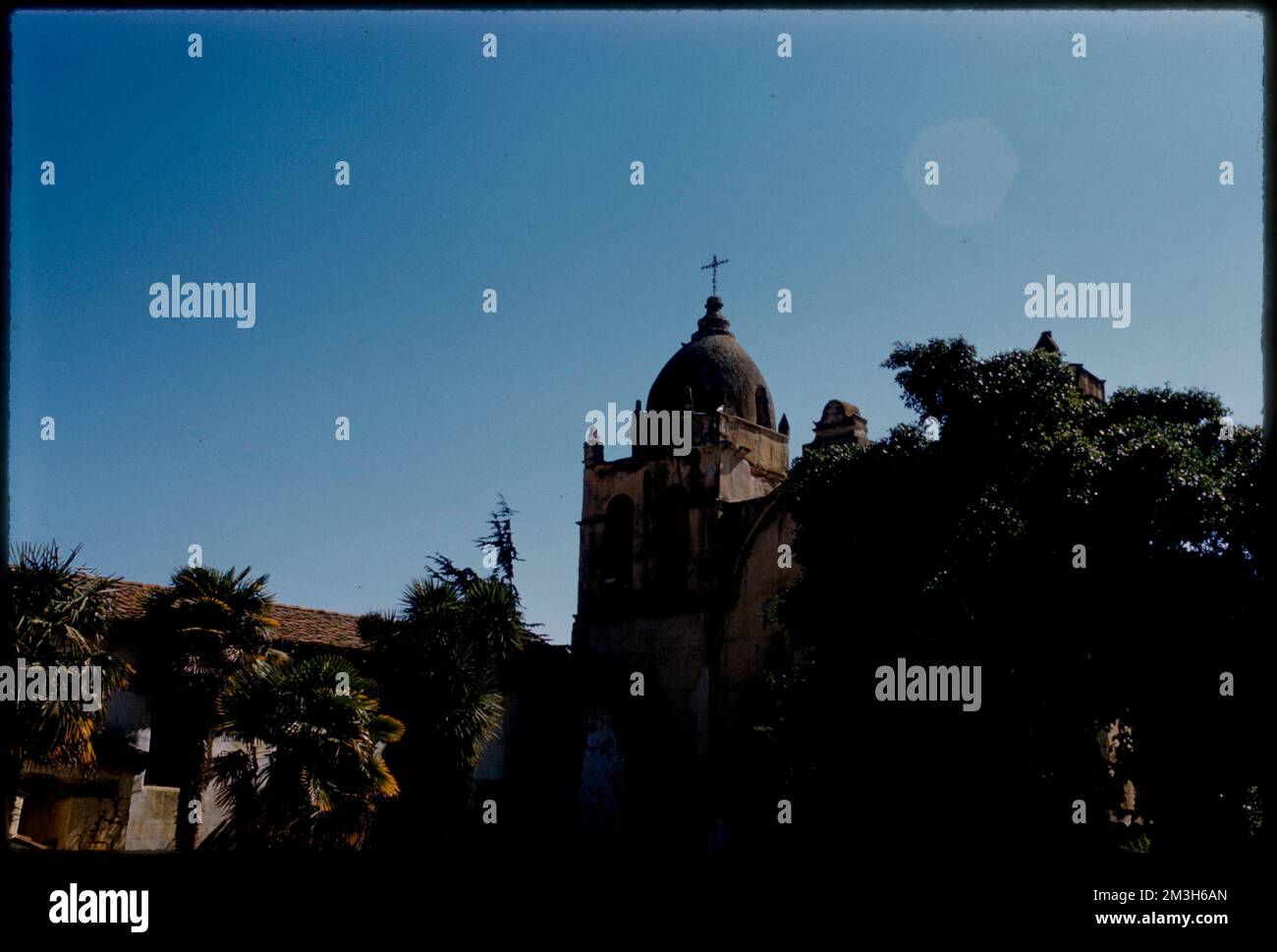

If you’ve seen other California missions, you’ll notice Carmel looks different. It’s not just a long adobe rectangle. The current stone church, completed in 1797 under Father Lasuén, has these distinct, curving walls.

Why? It’s basically because they used native sandstone quarried from the nearby Santa Lucia Mountains. This wasn’t some pre-fab design sent from Spain. It was a local adaptation. The walls are five feet thick at the base. They taper as they go up. This creates that specific, inward-leaning "beehive" look that makes the interior feel much tighter and more sacred than the airy, barn-like missions you see in places like San Miguel or San Luis Obispo.

The star window is the celebrity here. It’s technically a "Moorish" style window, which is a nod to the Spanish architectural roots influenced by North African design. It’s slightly off-center. It’s imperfect. And that’s what makes it feel human. In the 1930s, Harry Downie, a master restorer, spent nearly 50 years bringing this place back from literal ruins. When the Mexican government secularized the missions in the 1830s, the roof collapsed. Grass grew in the nave. What you see today is a painstaking reconstruction of what Downie thought it should be, based on old sketches and physical evidence.

The "Secret" Gardens and the Jo Mora Connection

Most tourists hit the basilica and leave. Big mistake. The grounds are where the real texture of the place lives.

🔗 Read more: Flights to Chicago O'Hare: What Most People Get Wrong

You’ve got the Mora Chapel. Inside, there’s an incredible cenotaph—a memorial monument—created by Jo Mora in 1924. It’s bronze and travertine. It’s massive. Mora wasn’t even Catholic, but he spent years documenting the mission and the local native cultures. His work is a weirdly perfect bridge between the romanticized "Spanish Colonial" era of the early 1900s and the actual history of the site.

Then there are the gardens. They grow everything from ancient olive trees to native sage. It’s a sensory overload. The smell of rosemary and damp stone is basically the "Carmel Mission scent."

Surviving the Secularization Era

History isn't a straight line. Between 1833 and the late 1800s, this place was a ghost town. The Mexican government took the land away from the Church. The mission was abandoned. Local ranchers used the outbuildings for storage. If it wasn't for the fact that the U.S. government—specifically Abraham Lincoln—signed the land back to the Catholic Church in 1859, the whole thing would probably be a pile of dust or a boutique hotel by now.

You can actually see the original land grant documents in the museum. It’s one of those rare moments where the Civil War era intersects with California mission history.

💡 You might also like: Something is wrong with my world map: Why the Earth looks so weird on paper

What to Do When You Actually Visit

If you’re planning a trip, don't just treat this as a photo op. To really "get" Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo, you need a strategy.

- Arrive early. The light hits the facade in a specific way around 9:30 AM. It makes the yellow sandstone glow.

- Check the museum first. Most people go church -> museum. Reverse it. Understanding the timeline of the Rumsen people and the secularization makes the church interior feel much more significant.

- Find the "Serra Cell." It’s a tiny, austere room where Junípero Serra supposedly slept. It’s a reality check on the lifestyle of these friars. No matter what you think of their mission, they weren't living in luxury.

- Visit the Cemetery. There’s a small cemetery to the side. It’s a mix of Spanish and indigenous remains. It’s a quiet place to sit and think about the sheer scale of the human experience that happened on this few acres of land.

The Modern Conflict: Preservation vs. Progress

Today, the mission is still an active parish. That’s the part people forget. It’s not just a museum; people get married here, have funerals here, and go to Mass every Sunday. This creates a weird tension. How do you preserve a 250-year-old adobe structure when hundreds of people are walking through it every day?

The 2012 seismic retrofitting was a massive undertaking. They had to strengthen the stone walls without ruining the aesthetic. It cost millions. And honestly, the work is never done. The salt air from the Pacific—only a few blocks away—eats at the sandstone. It’s a constant battle against the elements.

Actionable Insights for Your Visit

- Parking Hack: Don't try to park in the tiny lot right in front of the gate on a weekend. It’s a nightmare. Park a few blocks away in the residential area (check the signs!) and walk. The approach through the neighborhood gives you a better sense of how the mission sits in the valley.

- Photography: Tripods are usually a no-go inside the basilica. If you want that perfect shot of the star window, bring a lens with a wide aperture ($f/1.8$ or $f/2.8$) because it is dark in there.

- The "Secret" Library: Ask about the California Mission Library. It’s the oldest library in the state. You can't usually just walk in and browse, but they sometimes have special exhibits showing the original books brought over by the friars.

- The Native Perspective: Before you go, read a bit from the Ohlone perspective. The "Amah Mutsun Tribal Band" and other local groups have a lot of resources online. Seeing the mission through the eyes of the people who were there before the Spanish arrived changes everything.

Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo isn't a static monument. It's a living, breathing, and sometimes controversial piece of California's soul. It's beautiful, dark, complex, and absolutely worth more than a 15-minute stop.

Next Steps for Your Trip

Research the current museum hours on the official parish website, as they shift seasonally. If you’re coming from the north, take Highway 1 and exit at Rio Road; it’s the most direct route and avoids the downtown Carmel-by-the-Sea traffic. Consider pairing the visit with a trip to Point Lobos State Natural Reserve, just a few miles south, to see the landscape as it appeared before any of these stones were laid.