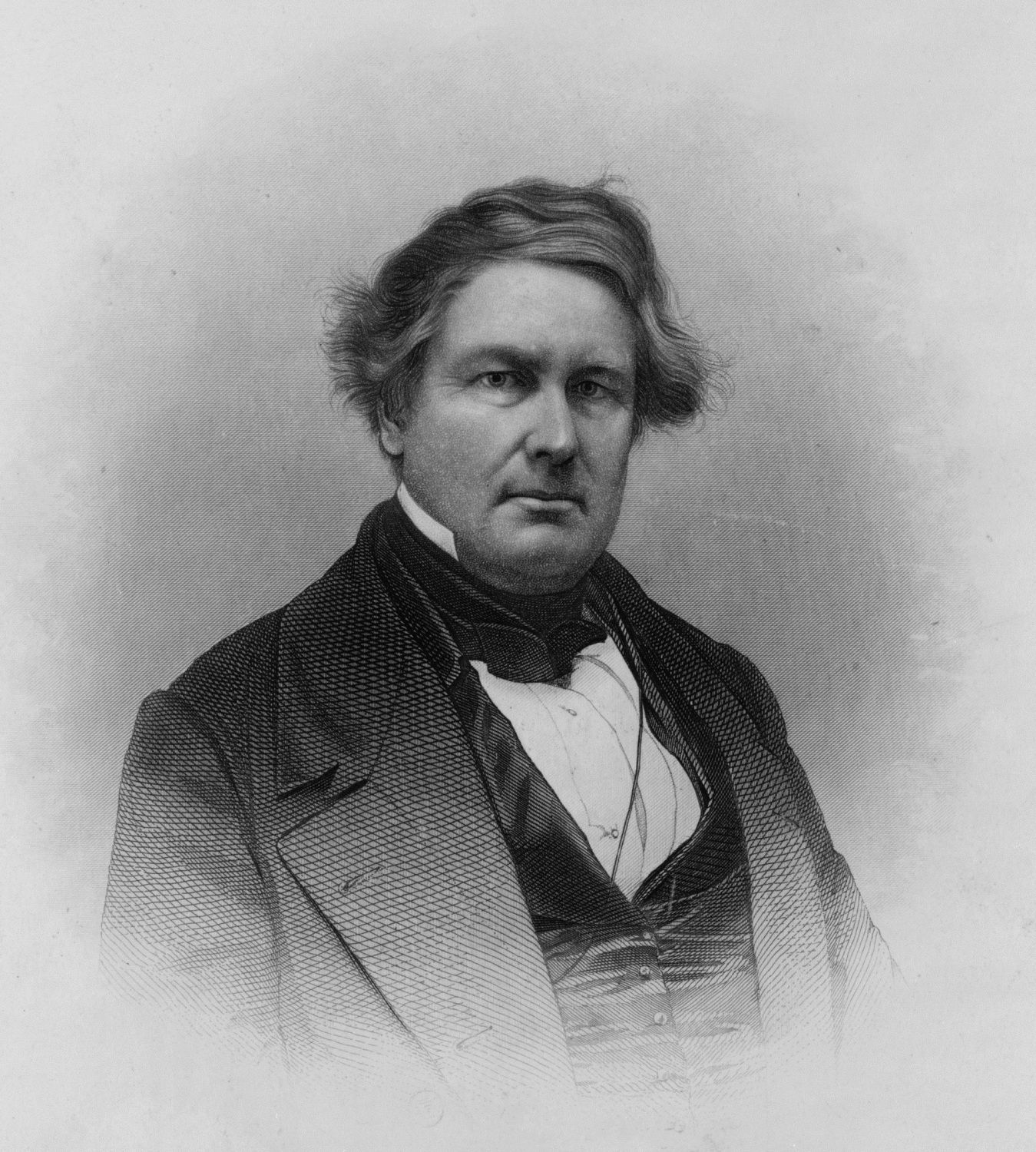

You’ve probably seen his name on a random street sign or maybe a middle school in the suburbs. Honestly, for most of us, Millard Fillmore is just the answer to a trivia question that nobody actually asks. He’s the "invisible" president. Tucked between the rough-and-tumble Zachary Taylor and the disastrous Franklin Pierce, Fillmore usually gets relegated to the "forgettable" pile of American history.

But here’s the thing. Millard Fillmore wasn’t just a placeholder. He was a man who rose from a dirt-floor log cabin to the highest office in the land, only to make a single decision that essentially nuked his own career and arguably the Whig Party along with it.

The Man Who Came From Nothing

He wasn't born into the elite. Not even close. Born in 1800 in the Finger Lakes region of New York, Fillmore’s childhood was basically a masterclass in frontier survival. His family was poor. Like, "tenant farmer" poor.

At 15, he was apprenticed to a cloth dresser. It was grueling, repetitive work. But Fillmore was obsessed with self-improvement. He reportedly bought a dictionary and hid it by his workstation just to learn new words while he worked. He didn't even see a library until he was 17.

Then he met Abigail Powers.

She was his teacher. She was also only two years older than him. They fell in love over books and ambition. Abigail was the one who pushed him to keep going, to study law, and to believe he was meant for more than a textile mill. It’s a bit of a rom-com setup, but it worked. By 1823, he was admitted to the bar.

A Career Built on "Anti"

Fillmore didn't start as a Whig. He actually got his start in the Anti-Masonic Party. If that sounds like a group of conspiracy theorists, you're not entirely wrong. It was the first "third party" in U.S. history, born out of a bizarre scandal involving the disappearance of a man who threatened to reveal Masonic secrets.

Eventually, he transitioned into the Whig Party under the mentorship of Thurlow Weed. He served in the New York State Assembly and then the U.S. House of Representatives. He was a "company man." Methodical. Reliable. He became the Chairman of the Ways and Means Committee.

Basically, he was the guy you wanted handling the paperwork, not necessarily the guy you expected to lead the nation.

The Accident of 1850

In 1848, the Whigs picked Zachary Taylor, a war hero who had never even voted, to run for president. They needed a "safe" Northerner to balance the ticket. Fillmore was the guy.

They won. But they didn't even meet until after the election.

Taylor died suddenly in July 1850. Some say it was the cherries and milk at a July 4th celebration; others say it was just general gastrointestinal failure. Regardless, the "Rough and Ready" General was gone, and "His Accidency"—a nickname Fillmore hated—was in.

When Fillmore took the oath, the country was a tinderbox. The big question? What to do with the massive amount of land won in the Mexican-American War. Would it be slave or free?

Taylor had been stubborn. He was ready to go to war with Texas over their borders and didn't care much for compromise. Fillmore was different. He was a peacemaker by nature, or maybe just a pragmatist. He fired Taylor’s entire cabinet and brought in Daniel Webster as Secretary of State.

📖 Related: The Boiling Water Christmas Tree Hack: Does It Actually Work?

The Compromise That Broke Him

This is where the story gets messy. Fillmore threw his weight behind the Compromise of 1850. It was a massive package of five bills designed to keep everyone from killing each other.

It felt like a win at the time. California came in as a free state. The slave trade was abolished in D.C. Texas got $10 million to back off New Mexico.

But then there was the Fugitive Slave Act.

This law was a nightmare. It required federal marshals and even ordinary citizens in the North to help catch and return escaped enslaved people. It denied those people a jury trial. To many in the North, this was a bridge too far. It turned their backyards into hunting grounds for Southern slave-catchers.

Fillmore signed it.

He didn't love slavery. In fact, he personally found it loathsome. But he loved the Union more. He believed that if he didn't sign that law, the South would secede and the country would dissolve right then and there. He chose the law over morality, hoping to buy time.

He bought eleven years. But he lost the North forever.

💡 You might also like: Why Every Picture of Virgin Mary Looks Totally Different

Life After the White House

The Whigs dumped him in 1852. They chose General Winfield Scott instead. Fillmore's political career should have ended there, but he had one more weird chapter left.

In 1856, he ran for president again. This time, he was the candidate for the Know-Nothing Party (officially the American Party).

They were an anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic group that thrived on the "nativist" fears of the era. It’s a dark stain on his legacy. Fillmore claimed he wasn't a bigot—he just wanted to preserve "traditional American values"—but when you’re the face of a party whose members literally tell people "I know nothing" when asked about their secret meetings, the optics aren't great.

He lost, winning only Maryland.

He spent his final years in Buffalo. He was actually a pretty great citizen there. He helped found the University of Buffalo, the Buffalo Historical Society, and the local SPCA. He was a guy who liked order. He liked institutions. He just couldn't figure out how to navigate the moral earthquake that was the 1850s.

Why Millard Fillmore Matters (Kinda)

We like our presidents to be heroes or villains. Fillmore was neither. He was a middle-manager trying to hold together a company that was already bankrupt.

If you want to understand why the Civil War happened, you have to look at the "failure of the middle." Fillmore represents the last gasp of the politicians who thought they could "compromise" their way out of a moral crisis.

He died in 1874 after a stroke. His last words were reportedly about some soup he was eating: "The nourishment is palatable."

It’s a fitting end for a man whose presidency was, well, palatable to some but ultimately lacked the substance to save a crumbling nation.

Actionable Takeaways for History Buffs

If you're digging into 19th-century politics, don't just stop at the "Big Names." Here is how to actually learn from the Fillmore era:

💡 You might also like: Weather for Pleasantville New Jersey: What Most People Get Wrong

- Study the Compromise of 1850: Don't just look at the dates. Read the personal letters of Daniel Webster and Henry Clay from that year. It shows how desperate they were.

- Visit Buffalo, NY: His house is gone, but the Buffalo History Museum and his gravesite at Forest Lawn Cemetery are surprisingly grand. It gives you a sense of his local impact.

- Trace the Third Parties: Look into the Anti-Masonic and Know-Nothing movements. They provide a blueprint for how populist "outsider" movements have functioned in America for 200 years.

You can actually find digitized versions of Fillmore's papers through the State University of New York (SUNY) Buffalo archives if you want to see the man's own handwriting and the logic behind his most controversial moves. It’s a lot more human than a textbook makes it out to be.

To truly understand the era, you should compare Fillmore's handling of the Fugitive Slave Act with the "Personal Liberty Laws" passed by Northern states in response. This legal tug-of-war is what eventually made the "Compromise" impossible to maintain.