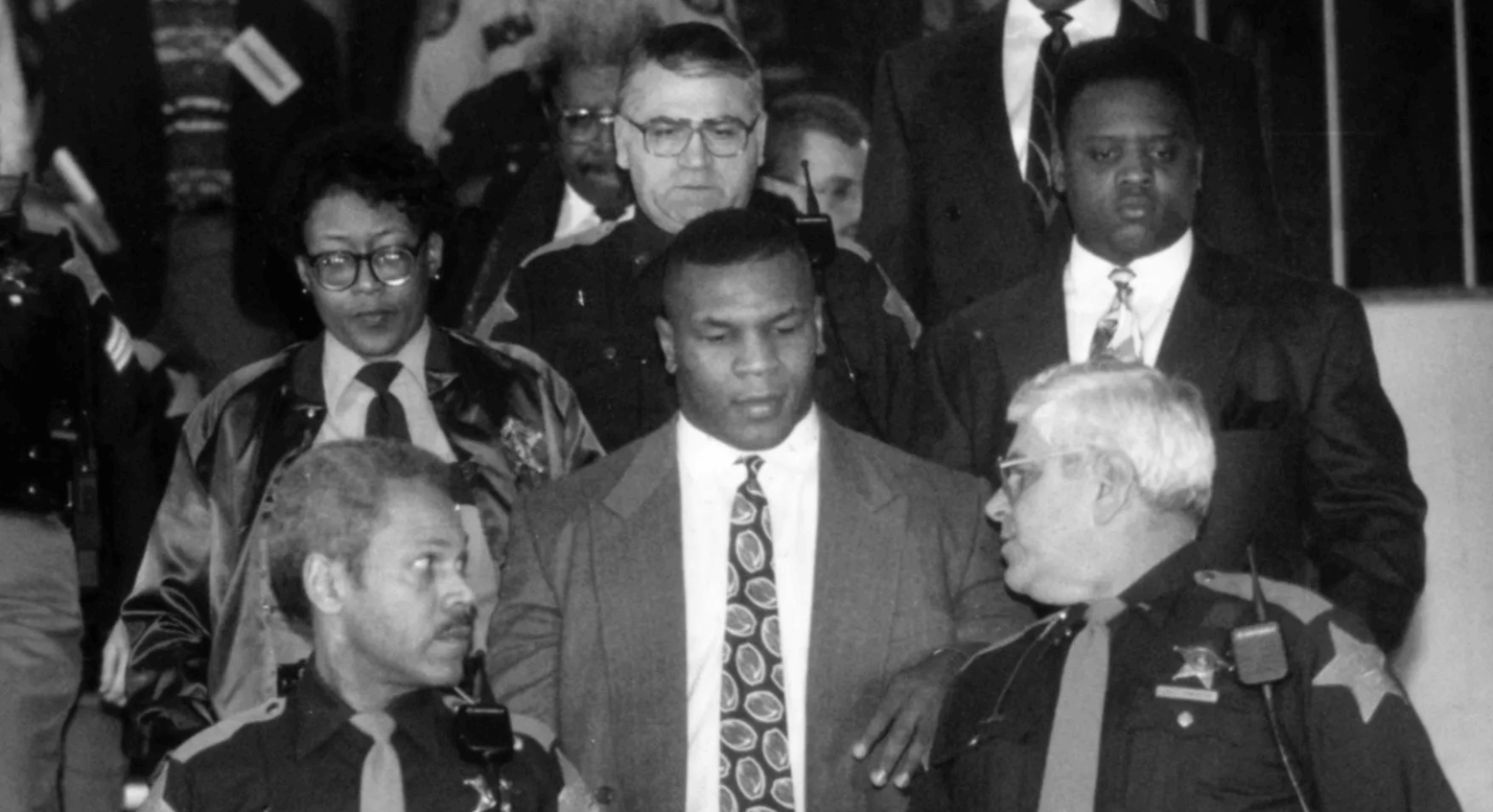

Most people remember the 1990s as the decade Mike Tyson went from the "Baddest Man on the Planet" to a number in the Indiana Department of Correction. He was at the absolute peak of his fame when it all came crashing down in an Indianapolis courtroom. But while the world was busy dissecting the trial, something much weirder and more personal was happening inside the Plainfield Correctional Facility.

You’ve probably heard the rumors. There’s been a lot of talk over the years about Tyson’s relationship with a particular prison counselor. It wasn't just your standard inmate-staff interaction. Honestly, the story sounds like something out of a movie, but Tyson himself has basically confirmed the wilder parts of it during various interviews later in his life.

The Counselor and the GED Deal

When Tyson entered prison in 1992, he was angry. He spent the first six months acting out, fighting guards, and getting tossed into solitary. He was miserable. He has often described that period as a "dream" he couldn't wake up from. But eventually, he had to figure out how to navigate the system if he ever wanted to get out early.

✨ Don't miss: A qué horas juega el Atlético de Madrid: Todo sobre el horario del Atleti hoy y esta semana

Enter the substance abuse counselor.

Tyson has been pretty open about the fact that he struggled with the educational requirements in prison. Specifically, he was failing his GED. In a widely discussed interview with Zab Judah, Tyson admitted that he ended up having a months-long affair with his prison counselor.

According to Mike, the deal was pretty straightforward. He wasn't passing the tests. She wanted him. They started a relationship, and suddenly, his academic troubles seemed to vanish. He’s joked about it since, saying he "slept with the counselor and passed." It sounds crazy, but in the chaotic environment of a high-profile incarceration, these kinds of power dynamics happen more often than the public realizes.

A Year Cut Short

This wasn't just about a diploma, though. That relationship played a massive role in his behavior and his eventual release. By getting on the "good side" of the staff, Tyson managed to get a year shaved off his sentence.

He was originally looking at a much longer stay, but he walked out in 1995 after serving three years. While his legal team, led by Alan Dershowitz, was busy filing appeals that went nowhere, it was the internal relationships—like the one with the mike tyson prison counselor—that actually moved the needle on his release date.

The Complicated Reality of Prison Life

It’s easy to look at this as just another "Iron Mike" story, but it highlights a really messy part of the justice system. Tyson has since become a vocal advocate for prisoner re-entry, arguing that the system is "debilitating, not rehabilitating." He’s mentioned that the only reason he survived was because he had already been "institutionalized" as a kid in New York juvenile centers.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Detroit Lions Thanksgiving 2024 Disaster Actually Proved They Are For Real

- He felt "safe" behind bars because it was a familiar environment.

- He used his time to read everything from Mao Zedong to X-Men comics.

- He even got a prison official pregnant, a bombshell he dropped during an ESPN interview years later.

The dynamic with the counselor wasn't an isolated incident of "celebrity privilege" either. It was a survival tactic. Tyson has noted that guards would often try to "break" him just to make a name for themselves. They’d subject him to humiliating body searches or taunt him with nicknames like "tree jumper" (prison slang for a rapist).

The Bobby Stewart Connection

To understand Tyson's relationship with authority figures in prison, you have to look back at where it all started. Long before Plainfield, a juvenile detention counselor named Bobby Stewart discovered Tyson’s boxing talent. Stewart was a former boxer himself and was the one who eventually introduced a young, troubled Mike to Cus D’Amato.

In a way, Tyson’s life has always been shaped by these "counselors." One discovered his talent; another helped him navigate the dark years of his 20s.

Lessons From the Plainfield Years

What can we actually learn from the mike tyson prison counselor saga? Honestly, it's a reminder that even the most famous people in the world are subject to the weird, often corruptible hierarchies of the prison system.

If you're looking for actionable insights into how this period changed Tyson—and what it means for the legal system—consider these points:

👉 See also: Texas Aggie Football Score Today: What Really Happened to the Season

- The Importance of Mentorship: Tyson’s life changed for the better when he had a positive counselor like Bobby Stewart and for the "easier" when he had the Plainfield counselor. It shows how much influence these figures have over an inmate's trajectory.

- Systemic Flaws: The fact that a world-famous athlete could trade favors for a GED and a shorter sentence proves how much "discretion" exists within prison walls. It’s not always about the law; sometimes it’s about who you know.

- Mental Health Awareness: Years later, in 1999, Tyson was thrown back into solitary in Maryland because he was denied his antidepressant medication (Zoloft). He’s since become an example of why mental health support is crucial for rehabilitation, not just punishment.

Tyson’s time in Indiana wasn't just a "break" from boxing. It was a transformational period that saw him convert to Islam, study history, and engage in some questionable behavior with the staff. It’s a messy, human story that defies the simple "hero or villain" narrative the media liked to push back then.

To really understand the Mike Tyson we see today—the philosophical, cannabis-growing, soft-spoken legend—you have to look at those three years in Plainfield. He went in as a warrior and came out as someone who realized that even the strongest man can be broken by a system, unless he finds a way to work it from the inside.

If you are researching the impact of incarceration on high-profile figures, focus your attention on the transition from "punishment" to "re-entry" programs. The data shows that inmates who have stable, even if unconventional, support systems during their time inside have a significantly lower recidivism rate once they return to the public eye.