You’ve seen them a thousand times. Those grainy, neon-colored images in textbooks that look more like modern art than actual science. We call them "micrographs," but for most students and hobbyists, they’re just a confusing mess of blobs. Honestly, looking at a microscope picture and label setup for the first time is overwhelming. You’re staring at a cell, trying to find the mitochondria, but everything just looks like purple static.

It’s hard.

The reality is that most people approach microscopy backwards. They look for the label first, then try to force their eyes to see the structure. That’s not how science works. Real microscopy is about pattern recognition and understanding how light (or electrons) interacts with organic matter. If you can’t identify a nucleus without a giant red arrow pointing at it, you aren't really seeing the cell. You're just reading a map.

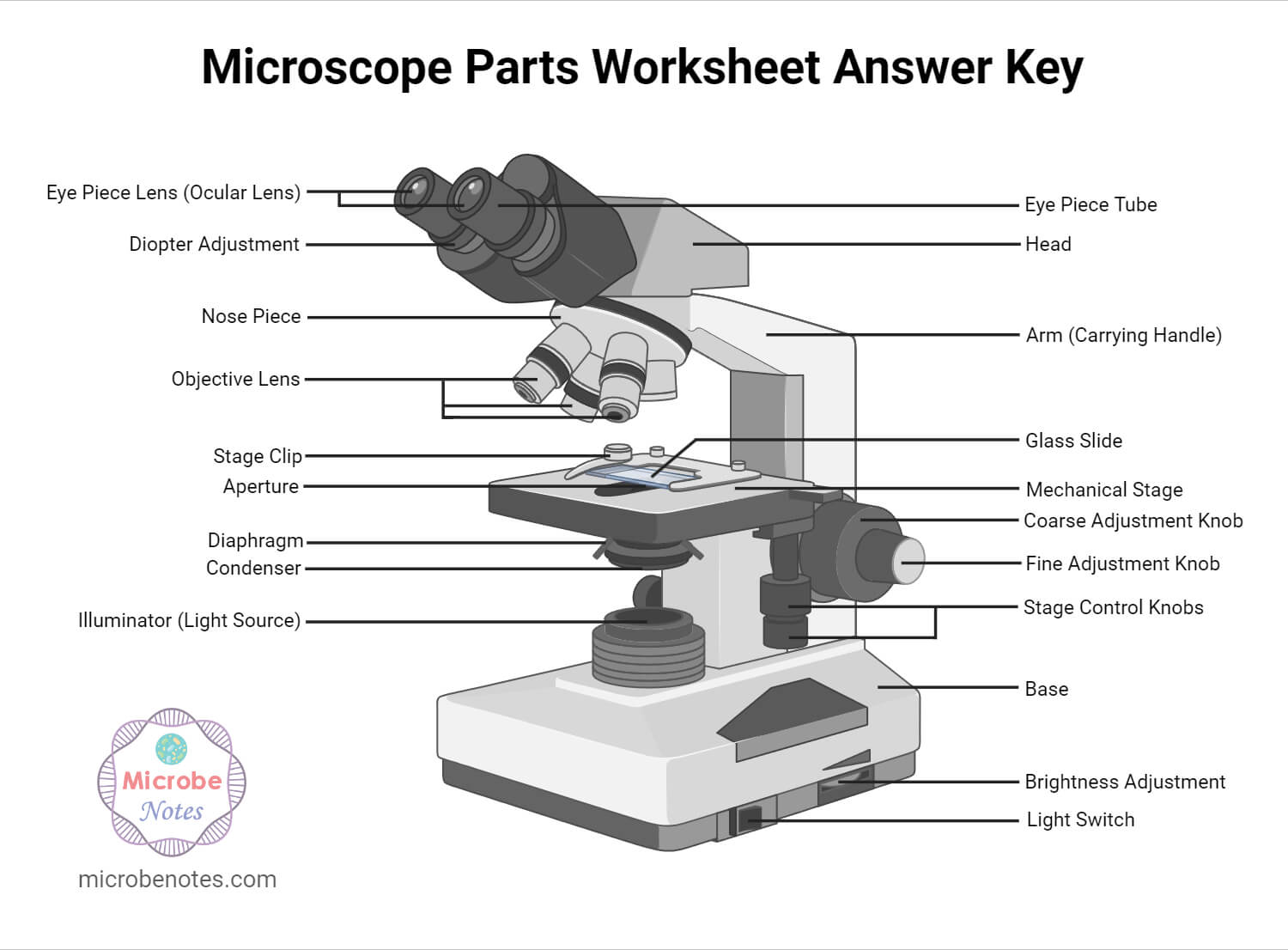

The Anatomy of a Proper Microscope Picture and Label

A "good" image isn't just about high resolution. It’s about context. When a researcher at a place like the Mayo Clinic or a lab at MIT publishes a microscope picture and label, they aren't just slapping text on a photo. They’re providing a data set. Every label serves a specific function, identifying the "organelles of interest" while ignoring the background noise.

Take a classic onion skin cell. It’s the "Hello World" of biology. In a standard light microscope view, you’ll see the cell wall—that’s the rigid outer frame. Then there’s the nucleus, usually a dark, circular spot. But here is where people trip up: the cytoplasm often looks empty. It isn’t. It’s packed with cytoskeleton filaments and vacuoles that just don’t pick up the stain well. If your label says "cytoplasm" and points to a white void, it’s technically correct but visually misleading.

Microscopy is essentially the art of staining. Without stains like Methylene Blue or Eosin, most biological samples are transparent. You’re looking at ghosts. The labels we use are actually markers for where the chemicals decided to stick. When you see a "nucleus" label, you’re actually seeing a "clump of DNA that reacted with a basic dye" label. Subtle difference, but a huge one for accuracy.

Why Scale Bars Matter More Than Labels

If I show you a picture of a "cell" but don't tell you if it’s 10 microns or 100 microns wide, the picture is scientifically useless. Scale bars are the most ignored part of any microscope picture and label documentation.

Think about it.

A human hair is about 70 microns wide. A red blood cell is about 8 microns. Without a scale bar, a photo of a grain of sand could look exactly like a photo of a planet. High-end journals like Nature or Science won't even look at an image if it lacks a micron marker. Labels tell you what it is; scale tells you how it exists in the physical world.

Digital zoom has made this worse. You can pinch-to-zoom on your phone or tablet, but that doesn't change the optical resolution. You’re just making the pixels bigger. A true labeled micrograph must account for the "Numerical Aperture" of the lens, which basically dictates how much detail the physical glass can actually capture before physics says "no more."

The Different Views: Light vs. Electron

We have to talk about the tech. A microscope picture and label from a standard compound light microscope looks nothing like one from a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM).

- Light Microscopes: These use photons. You get color, you can often see live cells moving, but you’re limited to about 2000x magnification. The labels here are usually simple: Cell Wall, Nucleus, Chloroplast.

- Electron Microscopes (SEM/TEM): These use electrons. The images are inherently black and white (any color you see is "false color" added later in Photoshop). The magnification can hit millions. Here, labels get intense. You’re looking at individual ribosomes or the double-membrane of a mitochondria.

It's sorta like comparing a hand-drawn map of a city to a satellite feed. Both are useful, but you use them for very different things. If you’re trying to label a virus, a light microscope is basically a paperweight. You need the big guns.

Common Mistakes in Labeling and Identification

I’ve graded hundreds of lab reports. The same errors pop up every single time.

First, people label bubbles. Seriously. Air bubbles under a cover slip are perfectly round, have thick black edges, and look "more real" than the actual specimen to an untrained eye. Students will confidently label an air bubble as a "vacuole." If your "organelle" looks like a perfect circle with a heavy border, it’s probably just air, guys.

Second is the "artifact" problem. Sometimes, during the slide preparation, the tissue tears or a piece of dust falls on the slide. These are called artifacts. A bad microscope picture and label will try to identify these as part of the biology. "Oh, that giant black line must be a specialized nerve fiber!" No, it's a hair from the lab tech’s sweater.

Nuance is everything. A real expert looks for symmetry and repetition. If you see something once, it’s a glitch. If you see it in every single cell in the same spot, it’s a feature.

The Rise of AI in Micrograph Interpretation

Things are changing fast. By 2026, we’ve seen a massive shift toward automated labeling. Software like ImageJ has been around forever, but new AI-driven tools can now scan a microscope picture and label thousands of individual cells in seconds.

✨ Don't miss: Nikola Tesla: Man Out of Time and Why His Wildest Dreams Finally Make Sense

This is huge for cancer research. Pathologists used to spend hours squinting at biopsies to count "mitotic figures" (cells in the act of dividing). Now, an algorithm can do it with 99% accuracy. But here’s the kicker: the AI still needs a human to "ground truth" the labels. If the human teaches the AI that a dust mote is a cell, the AI will ruin the whole data set.

We are entering an era of "Augmented Microscopy." Your eyepiece might soon have an OLED overlay that labels the structures in real-time as you move the slide. It’s basically Pokémon GO but for microbiology.

How to Create a Professional Labeled Micrograph

If you’re doing this for a school project, a blog, or a research paper, don't just use Microsoft Paint.

- Capture the Cleanest Image Possible: Clean your lenses with lens paper (not your shirt!). Use the fine adjustment knob. If it’s blurry, the labels won't save it.

- Use Straight Leader Lines: Your label lines should never cross. It’s a cardinal sin in scientific illustration. Use thin, solid lines that stop exactly at the edge of the structure.

- The "Thirds" Rule: Don't crowd the center. Place your labels in the margins and draw lines inward. It keeps the actual specimen visible.

- Include Metadata: Always write down the magnification (e.g., 400x) and the stain used. Without the stain name, someone else can't replicate your work.

Practical Steps for Better Results

Stop looking for "perfection." Biological samples are messy. They are wet, squishy, and rarely look like the 3D rendered animations you see on YouTube.

If you want to get better at identifying structures in a microscope picture and label, start by drawing them by hand. It sounds old-school, but the act of translating a 3D object under a lens onto a 2D piece of paper forces your brain to understand the geometry. Look at the work of Santiago Ramón y Cajal. He’s the father of neuroscience, and his hand-drawn labeled micrographs of brain cells from a hundred years ago are still used today because his eye for detail was better than most modern cameras.

Next time you’re looking at a slide, don't just snap a photo and walk away. Change the lighting. Move the diaphragm. See how the "labels" change when the shadows shift. Microscopy is a dynamic process, not a static one.

To improve your own microscopy work immediately:

- Verify your magnification: Multiply the eyepiece (usually 10x) by the objective lens (4x, 10x, 40x, or 100x).

- Use a neutral background: If you’re labeling for a presentation, use a white or light gray font with a thin black "halo" or shadow so it’s readable on both dark and light parts of the image.

- Check for inverted images: Remember that many microscopes flip the image. Your "top left" is actually the "bottom right" of the physical slide. Keep this in mind if you're labeling directional growth in plants or embryos.

- Focus on the edges: When identifying a cell, find the membrane first. Once you have the boundary, everything inside becomes much easier to categorize.