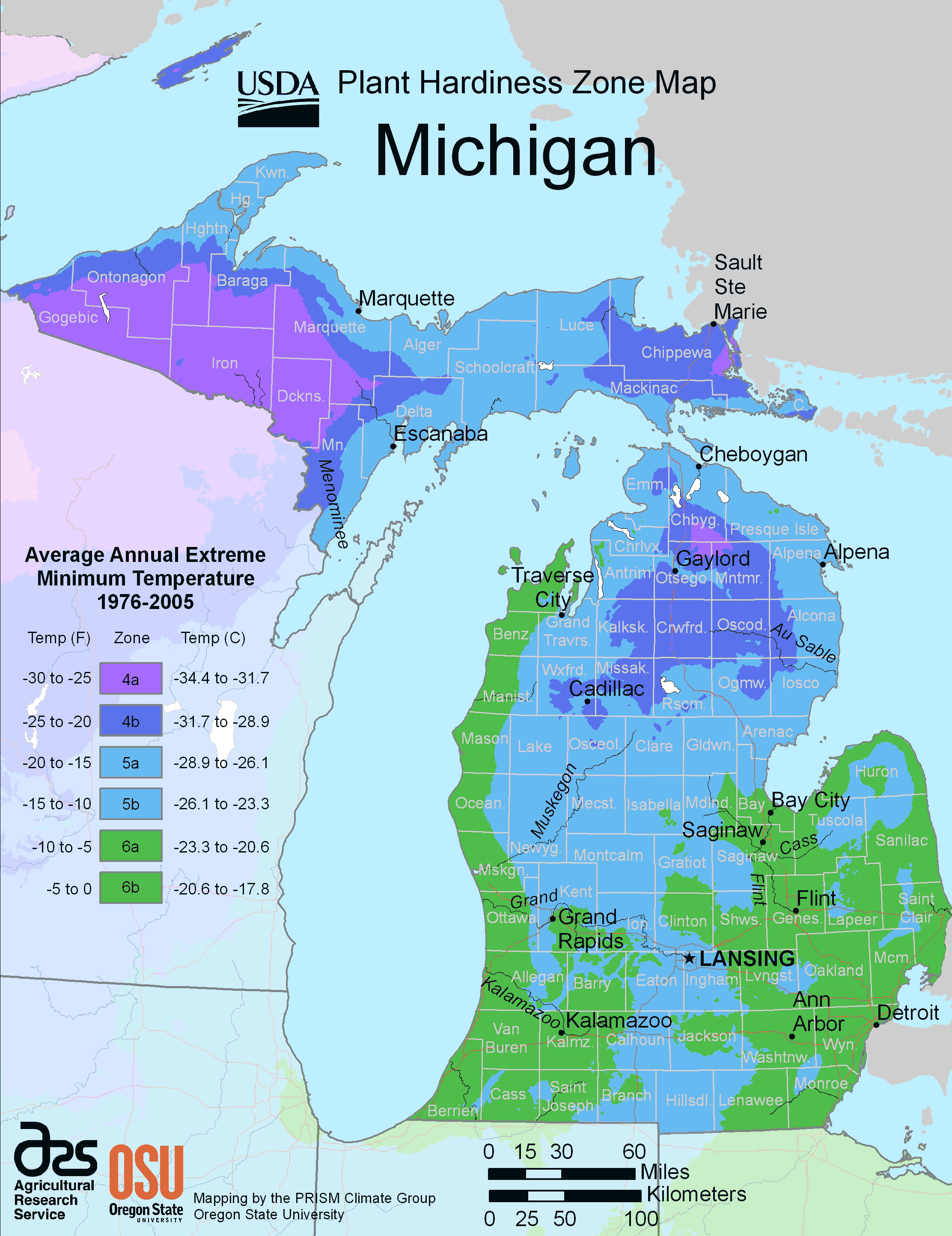

Michigan is a bit of a horticultural nightmare if you’re looking for consistency. Honestly, trying to pin down a single "Michigan climate" is like trying to catch a Great Lakes wave in a bucket. One day you're wearing shorts in Traverse City, and the next, a frost advisory is killing your expensive annuals. If you’ve spent any time looking at the Michigan growing zone map, you probably noticed those colorful bands shifting. In late 2023, the USDA dropped a massive update to their Plant Hardiness Zone Map, and for many Michiganders, things got... warmer. Sorta.

It's not just about the lines on a map.

The reality is that Michigan is basically a giant thumb stuck into a massive thermal regulator. Those lakes—Superior, Michigan, Huron, and Erie—dictate exactly what you can grow and when you can grow it. If you live in Berrien County, you’re playing a different game than someone in Marquette. Even within a single city like Grand Rapids, the "zone" can feel like it flips depending on how many paved driveways or old oak trees are on your block.

The 2023 USDA Shift and Your Garden

The most recent update to the Michigan growing zone map wasn't just a minor tweak; it was a wake-up call for a lot of northern gardeners. Across the state, many areas shifted about a half-zone warmer. What used to be a solid 5b might now be labeled as 6a. This happens because the USDA calculates these zones based on the average annual extreme minimum winter temperature. They look at a 30-year period. In the most recent data set (1991–2020), our winters just haven't been hitting those bone-chilling lows as consistently as they did in the mid-20th century.

But don't go buying a palm tree yet.

Just because the "average" low is warmer doesn't mean a polar vortex won't swing down from Canada and scream through your yard at $-25^{\circ}F$. That's the danger of these maps. They represent averages, not guarantees. A plant rated for Zone 6 might survive three mild winters only to be obliterated by one "old-fashioned" Michigan January. Experts like those at the MSU Extension often remind folks that while the map shifted, our erratic spring freeze-thaw cycles haven't gone anywhere. In fact, they might be getting more unpredictable.

Understanding the Numbers

When you look at the Michigan growing zone map, you're seeing numbers ranging from roughly 4a in the western Upper Peninsula to 6b or even 7a in tiny pockets of the southeast and along the Lake Michigan shoreline.

Zone 4? That’s cold. We’re talking average lows of $-30^{\circ}F$ to $-20^{\circ}F$. If you're gardening in Iron River, you're looking at short seasons and a very specific list of hardy perennials.

Zone 6? That’s the "sweet spot" for many fruit growers. This covers much of the southern Lower Peninsula and the "Fruit Belt" hugging the western coast. Here, the lake effect keeps the temperatures from dropping too fast in the fall and prevents them from spiking too early in the spring. It’s a buffer. Without it, the Michigan cherry and wine industries wouldn't exist as we know them.

The "Lake Effect" Lie

People talk about the lake effect like it's a warm blanket. It's more like a heavy, damp shield. While the Michigan growing zone map shows these nice, neat lines, the actual experience on the ground is way messier.

Take the "Banana Belt" of West Michigan. If you are within five to ten miles of Lake Michigan, you might be in Zone 6a. Go fifteen miles inland? You’ve dropped back into 5b or even 5a. The water holds heat longer than the land, which delays the first frost. In the spring, the cold water keeps the land cool, which—counter-intuitively—is a good thing. It prevents fruit trees from budding too early only to be killed by a late April frost.

Then there’s the snow.

In places like Houghton or Munising, the map says it’s Zone 4 or 5. Cold, right? But the massive amounts of lake-effect snow actually act as insulation. A plant might survive a Zone 4 winter better under three feet of powder than a plant in a Zone 6 Detroit suburb where the ground freezes solid and stays bare. Snow is the poor man’s mulch. Without it, root systems are vulnerable to "heaving," where the ground freezes and thaws, literally spitting your perennials out of the dirt.

Microclimates: Your Yard vs. The Map

The biggest mistake gardeners make is trusting the Michigan growing zone map more than their own eyes. Maps are macro. Gardening is micro.

Your backyard has its own climate. Do you have a brick wall facing south? That’s a heat sink. It’ll stay warmer late into the night, potentially letting you grow something a half-zone more tender than your neighbor. Do you live at the bottom of a hill? Cold air is heavy; it sinks. You’ve got a "frost pocket." You might lose your tomatoes two weeks before the guy at the top of the hill does.

Urban heat islands are another huge factor. Detroit and Grand Rapids stay significantly warmer than the surrounding rural townships. All that asphalt and concrete absorbs solar radiation all day and bleeds it out at night. This is why you’ll see certain shrubs thriving in a downtown parking lot planter that would struggle in a windy field in Lapeer.

Soil: The Hidden Variable

You can't talk about zones without talking about what's under your fingernails. Michigan's "mitten" is a mix of heavy clay, glacial till, and pure sand.

💡 You might also like: Beige Pants and White Shirt: Why This Simple Combo Always Wins

- The Thumb and Southeast: Lots of heavy clay. It holds water. In a cold winter, wet roots are dead roots. You might be in a warmer zone, but poor drainage will kill "hardy" plants faster than the temperature will.

- West Michigan: Sand. Everywhere. It drains instantly. It also gets hot fast and cools down fast.

- Northern Michigan: Acidic soils, often rocky. If you’re trying to grow blueberries, you’re in luck. If you want lilacs, you might be fighting a pH battle.

What Most People Get Wrong About Hardiness

"Hardiness" is a misleading word. We tend to think it means "toughness," but in the context of the Michigan growing zone map, it literally only refers to cold tolerance.

A plant can be "hardy" to Zone 5 but still die in Michigan because of:

- Humidity: Our summers are soup. Plants from the high desert might handle our winters but rot in our August humidity.

- Day Length: The UP gets way more daylight in the summer than the Ohio border. Some plants are sensitive to that "photoperiod."

- Pests: Our mild winters (thanks, Zone 6) mean more bugs survive. Emerald Ash Borer, Spotted Wing Drosophila, and even simple aphids get a head start when it doesn't get cold enough to kill their eggs.

Practical Steps for Michigan Gardeners

Don't just look at the map and head to the big-box store. Those stores buy plants for the whole Midwest. They’ll sell you a "Zone 6" hibiscus in a "Zone 5" town because it looks pretty in May. By next May, it’ll be compost.

First, find your specific coordinate. Don't just look at the state map; use the USDA's zip code lookup tool. If you're on a boundary line, always assume you're in the colder zone. It's safer. If you're in a 6a area that was 5b two years ago, keep buying 5b plants. Think of that extra half-zone as a safety margin, not an invitation to plant citrus.

Second, watch your "Last Frost Date." In Michigan, the "official" date is often mid-May, but for many of us, Memorial Day is the only truly safe bet. My grandmother used to say, "Never put your peppers in the ground until you can sit on the bare dirt with your bare butt and not get a chill." While I don't recommend that for several legal and comfort reasons, the sentiment holds. Soil temperature matters more than air temperature for annuals.

Third, lean into native species. Michigan natives like Asclepias (Milkweed), Echinacea (Coneflower), and Oak or Maple trees don't care about a map update. They've been vibrating with the Great Lakes' moods for thousands of years. They know how to handle a freak April blizzard and a 95-degree July.

Fourth, use protection. No, really. If you're pushing the zone—maybe trying to grow a semi-hardy fig or a fancy hydrangea—use burlap wraps and heavy mulching. The goal is to keep the plant dormant. The "yo-yo" effect of Michigan winters (45 degrees on Monday, 10 degrees on Tuesday) is what kills plants. It's called "sunscald" or "bark splitting." The sun warms the tree trunk during the day, the sap starts moving, and then the sun sets, the temp drops, and the sap freezes, expanding and literally exploding the bark. Wrapping trunks helps prevent this.

Real Talk on the Future

The Michigan growing zone map is going to keep changing. We're seeing a northward migration of species. You'll see more southern oaks moving into the lower counties. You'll see the "corn belt" pushing further into the "cherry belt."

Climate change isn't just "warming"; it's "weirding." We get more intense rain events and longer dry spells. Gardening in Michigan now requires more than just knowing your zone. It requires being an amateur meteorologist and a soil scientist.

Check the map. Use it as a guide. But trust the local old-timer who has been growing tomatoes in your specific neighborhood for forty years. They know things the satellites don't.

Actionable Next Steps

- Go to the USDA website and type in your exact zip code to see if your zone changed in the latest update.

- Keep a garden journal for one full year. Note the date of your first and last frosts. This is more accurate for your specific yard than any state-wide map.

- Test your soil pH. Knowing your zone is useless if your soil chemistry is locking out the nutrients your plants need to survive the winter.

- Invest in "Season Extenders." If you're in a colder zone (4 or 5), look into cold frames or "low tunnels." These can effectively move your garden one full zone south by trapping ground heat.

- Visit a local, independent nursery rather than a national chain. Local owners usually won't stock plants that can't survive the local winter, regardless of what the new map says.