If you walked into the 75th Precinct in East New York during the late 1980s, you weren't just walking into a police station. You were walking into the headquarters of a criminal enterprise. At the center of it all was Michael Dowd police officer, a man who would eventually be labeled the "dirtiest cop in New York City history."

He wasn't just taking a free sandwich or a few bucks to overlook a double-parked car. Dowd was running his own drug ring. He was protecting kingpins. He was robbing rival dealers at gunpoint while wearing a shield and a Glock.

Honestly, the sheer scale of the graft is hard to wrap your head around. At his peak, Dowd was pulling in roughly $8,000 a week just from one dealer, Adam Diaz. Totaled up, he was pocketing tens of thousands of dollars every single week while his honest colleagues were struggling to survive on a $600 paycheck. It’s a story of greed, sure, but it’s also a story about what happens when the people paid to protect us decide the rules just don't apply to them.

The Making of a "Criminal Cop" in the 75th

Michael Dowd didn't join the NYPD in 1982 with the intention of becoming a drug lord. He was just a kid from Brentwood, Long Island, the son of a firefighter. He took the police test because it came back first. That's it.

The 75th Precinct back then was a war zone. We’re talking over 100 murders a year in a single jurisdiction. The crack epidemic was exploding, and the streets were literally paved with money. Dowd saw kids half his age making more in a night than he made in a year. The temptation didn't just knock; it broke the door down.

His first bribe? It was $200 and a lobster lunch.

💡 You might also like: 39 Carl St and Kevin Lau: What Actually Happened at the Cole Valley Property

Pretty small time, right? But that’s how it starts. Within a few years, he was the lead "enforcer" for the Diaz organization. He’d use his police radio to tip off dealers about upcoming raids. He and his partner, Ken Eurell, would drive around in their patrol car with kilos of cocaine tucked under the seat.

Why Nobody Stopped Him

You’d think someone would notice the patrol officer driving a brand-new red Corvette to work. They did. In fact, internal affairs received at least 16 separate complaints about Michael Dowd police officer over several years. They were told he was selling drugs, robbing people, and hanging out with known traffickers.

They did basically nothing.

The "Blue Wall of Silence" wasn't just a metaphor; it was a physical barrier. Cops didn't snitch on cops. Even the honest ones often looked the other way because the culture of the department at the time was "us versus them." If you weren't with the guys in blue, you were nobody. This systemic failure eventually led to the Mollen Commission, a massive investigation that changed how the NYPD handles internal corruption forever.

The Downfall and The Seven Five

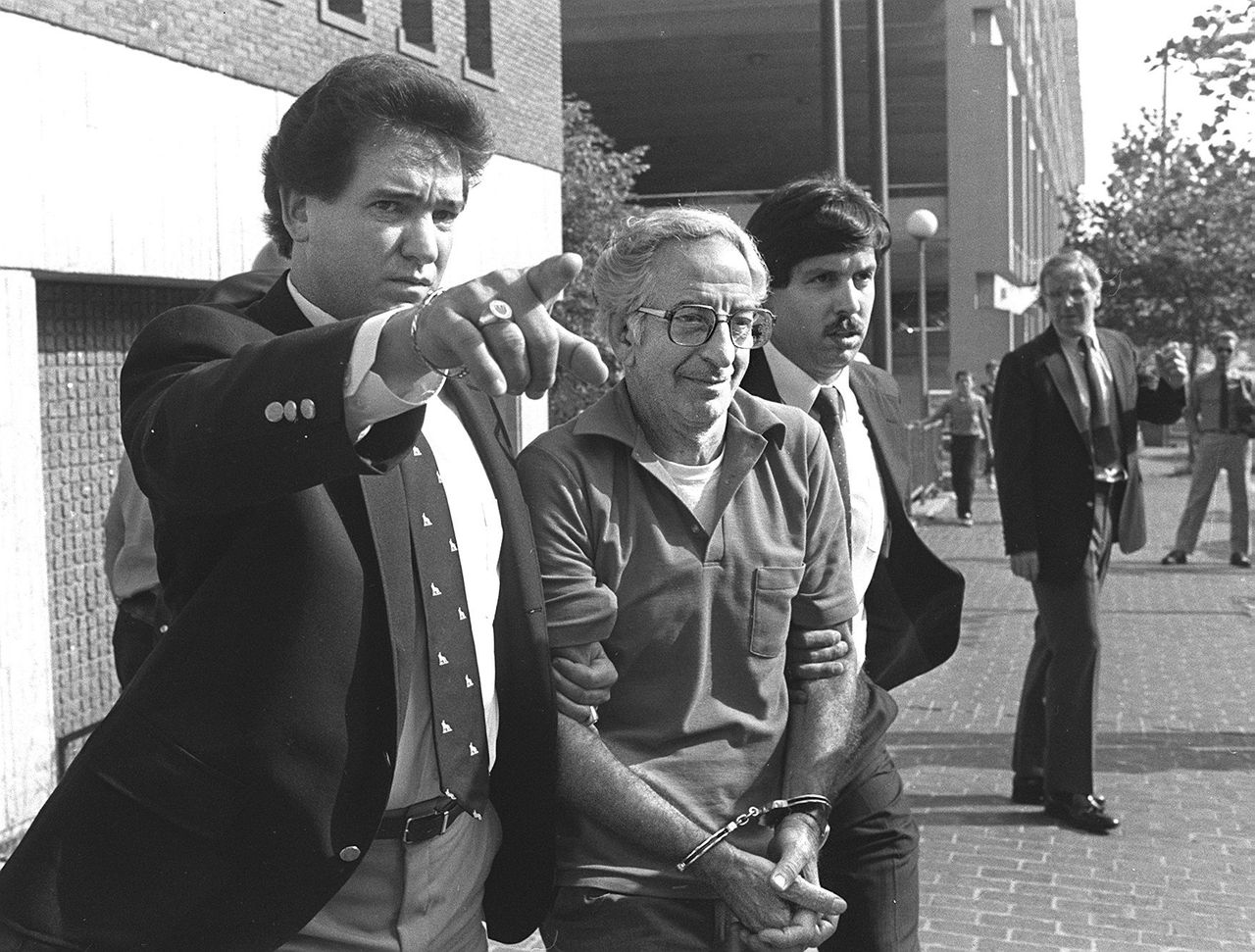

Everything came crashing down in 1992. But it wasn't the NYPD that caught him. It was the Suffolk County Police Department. They were investigating a local drug ring and kept hearing a voice on the wiretaps that sounded suspiciously like a cop.

📖 Related: Effingham County Jail Bookings 72 Hours: What Really Happened

It was Mike.

He was arrested in July 1992. The details that came out during his testimony were like something out of a Scorsese movie. He admitted to:

- Protecting drug "supermarkets" in Brooklyn.

- Stealing $8,000 from a duffel bag during a domestic dispute call.

- Plotting to kidnap a Colombian woman to pay off a debt.

- Drinking vodka and doing lines of coke while on duty in his patrol car.

Dowd was eventually sentenced to 14 years in federal prison, of which he served about 12 and a half. His partner, Ken Eurell, fared much better—he wore a wire, testified against Dowd, and walked away without serving a day. If you’ve seen the documentary The Seven Five, you know the tension between those two is still thick enough to cut with a knife.

Life After Prison: Can a Dirty Cop Find Redemption?

Since his release in 2005, Michael Dowd hasn't exactly hidden from his past. He’s become something of a public figure in the true crime world. You’ve probably seen him on The Diary of a CEO or various Netflix docs.

He's very open about what he did. He doesn't make excuses, though he does explain the "why." He’s worked as a consultant, helped with suicide prevention programs for first responders, and even spoken to current police officers about the slippery slope of corruption.

👉 See also: Joseph Stalin Political Party: What Most People Get Wrong

It’s a weird spot to be in. Some people see him as a reformed man who paid his debt and is now trying to do good. Others think he’s just a "coward and a thief" who is now profiting off his crimes through book deals and movie rights.

Lessons for Modern Law Enforcement

The Michael Dowd police officer case is still taught in police academies today as the ultimate cautionary tale. It’s not just about the "bad apple" theory. It's about the "rotten barrel." When the leadership ignores the red flags and the culture rewards silence over integrity, you get a Michael Dowd.

Today’s NYPD is much different, mostly because of the safeguards put in place after his trial. There’s more oversight, more body cams, and more accountability. But as Dowd himself has said in interviews, there’s a little bit of "larceny in everybody." The system has to be stronger than the individual's temptation.

Next Steps for Understanding the Case:

- Watch the Documentary: The Seven Five (2014) is the definitive account. It features actual surveillance footage and raw interviews with Dowd, Eurell, and Adam Diaz.

- Read the Mollen Commission Report: If you want the technical details on how the NYPD failed to catch him, the 1994 report is a fascinating, if depressing, read on institutional rot.

- Compare the Stories: Listen to Mike Dowd's recent podcast appearances and then read Ken Eurell’s book, Betrayal. The discrepancies between their versions of events tell you a lot about the nature of loyalty among thieves.

- Analyze Current Reforms: Look into the "Internal Affairs Bureau" (IAB) restructuring that happened post-1994 to see how Dowd’s crimes directly influenced modern police policy.