It was barely 80 degrees in Mexico City on October 16, 1968. Not exactly scorching, but the air inside the Estadio Olímpico Universitario felt heavy. It was thin, too—the high altitude made everyone a little lightheaded. Tommie Smith had just obliterated the world record in the 200-meter dash, finishing in 19.83 seconds. He did it with a strained groin muscle. John Carlos took the bronze.

What happened next changed everything.

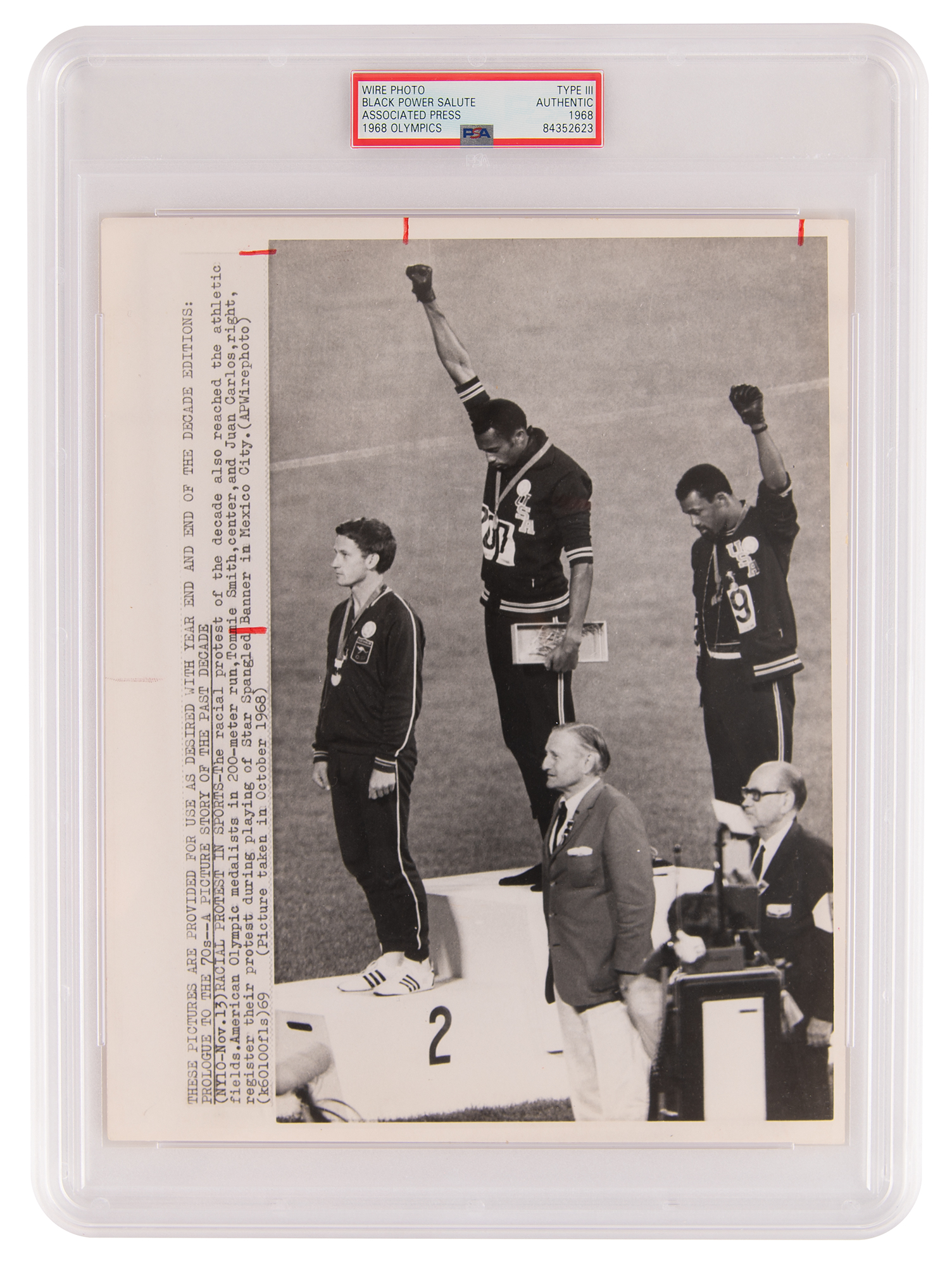

You’ve seen the photo. It’s arguably the most iconic image in sports history. Two men standing on a podium, heads bowed, black-gloved fists thrust into the air. It’s often called the Mexico City Olympics 1968 black power salute, but if you stop there, you’re missing about 90% of the nuance. This wasn't just a spontaneous "angry" outburst. It was a meticulously planned, deeply symbolic silent protest that had been brewing for over a year under the guidance of a sociologist named Harry Edwards and the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR).

The Man in the Middle You Probably Ignore

Everyone looks at Smith and Carlos. Hardly anyone looks at Peter Norman.

Norman was the Australian silver medalist. He was white, a salvationist, and a world-class sprinter. People often assume he was just a bystander caught in a historical whirlwind. Wrong. Norman was fully in on it. When Smith and Carlos told him what they planned to do, Norman didn't flinch. He actually suggested they share the gloves because Carlos had forgotten his pair at the Olympic Village. That’s why Smith’s right hand is up and Carlos’s left hand is up—they were wearing the same pair of gloves.

Norman asked for an OPHR badge to wear on his podium jacket to show solidarity. He knew the risks. He basically committed career suicide in that moment to stand up for human rights.

Symbols You Might Have Missed

The Mexico City Olympics 1968 black power salute wasn't just about the fists. Every single thing they wore—or didn't wear—meant something specific.

They walked to the podium in black socks and no shoes. Why? To represent African American poverty. They wore beads and scarves to protest lynchings and the "un-christened" deaths of Black people throughout history. Smith wore a black scarf. Carlos had his tracksuit top unzipped—a huge violation of Olympic protocol—to show solidarity with blue-collar workers.

💡 You might also like: Navy Notre Dame Football: Why This Rivalry Still Hits Different

They weren't just "protesting." They were mourning.

Then there’s the glove thing. It’s kind of wild that the most famous gesture in sports was a literal last-minute improvisation because of a forgotten accessory. If Carlos hadn't left his gloves behind, they both would have had a pair, and the visual of the mirrored fists might never have existed. History is weird like that.

The Backstory: It Almost Didn't Happen

The OPHR originally wanted a total boycott of the Games. Harry Edwards, a massive figure in sports sociology, argued that Black athletes shouldn't be "performing" for a country that treated them like second-class citizens back home. This was 1968. Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated in April. Robert F. Kennedy in June. The world was on fire.

The boycott didn't stick. Athletes like Smith and Carlos decided that showing up and winning—then using that platform—was more powerful than staying home. They were right. If they hadn't competed, we wouldn't be talking about this today.

The Immediate, Brutal Fallout

The reaction was instant and ugly.

Avery Brundage was the President of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) at the time. He’s a controversial figure, to put it mildly. He was the same guy who didn't object to the Nazi salute during the 1936 Berlin Olympics, claiming it was a "national salute." But a silent protest against racism? He deemed that a "violent" political statement that had no place in the "apolitical" Olympics.

Brundage ordered Smith and Carlos suspended from the U.S. team and banned from the Olympic Village. When the U.S. Olympic Committee hesitated, Brundage threatened to ban the entire U.S. track team. The Americans folded. Smith and Carlos were kicked out within 48 hours.

📖 Related: LeBron James Without Beard: Why the King Rarely Goes Clean Shaven Anymore

Back home, they were pariahs. They received death threats. Their families suffered. They struggled to find work for years. People called them traitors. Time magazine replaced their "Faster, Higher, Stronger" motto with "Angrier, Nastier, Uglier." It was a total character assassination.

Peter Norman’s Forgotten Sacrifice

Australia treated Peter Norman even worse, in some ways. He was never picked for the Olympics again, despite qualifying repeatedly. He was ostracized by the Australian sporting establishment for decades. When Australia hosted the 2000 Sydney Games, they didn't even invite him to be part of the festivities.

He never recanted.

When Norman died in 2006, Tommie Smith and John Carlos were his pallbearers. They flew to Australia to carry their friend to his grave. That’s the kind of bond this moment created. It wasn't just a political stunt; it was a life-altering pact of conscience.

Why the Mexico City Olympics 1968 Black Power Salute Still Hits Different

Context matters. This wasn't a PR-managed "social justice" campaign with corporate backing and hashtagged jerseys. This was three guys standing on a block of wood in front of the entire world, knowing they were potentially destroying their lives.

Today, we see athletes take a knee or wear slogans on their shoes. That’s fine. But in 1968, there was no safety net. No Nike endorsement for "taking a stand." They lost everything.

It’s also important to realize that the Mexico City Olympics 1968 black power salute occurred during a Games that were already soaked in blood. Just ten days before the opening ceremony, the Mexican government massacred hundreds of protesting students in the Tlatelolco massacre. The "Silent Protest" wasn't happening in a vacuum; it was happening in a city where the government had literally just killed its own youth to ensure the Games went off without a hitch.

👉 See also: When is Georgia's next game: The 2026 Bulldog schedule and what to expect

The Complexity of the Gesture

One thing people often get wrong is the "Black Power" label. While the media immediately branded it that way, Tommie Smith later described it as a "human rights salute." He felt the term "Black Power" was being used to scare white people and detract from the actual message of equality.

Smith and Carlos weren't there to promote a specific organization. They were there to highlight a global struggle. They bowed their heads during the anthem because they felt the words of "The Star-Spangled Banner" didn't apply to them or their people. They didn't hate the country; they were disappointed in it. There’s a huge difference, though people in 1968 weren't interested in that kind of nuance.

The Long Road to Redemption

It took decades for the narrative to flip.

In 2005, San Jose State University (where Smith and Carlos competed) erected a massive statue of the moment. Interestingly, the silver medal spot on the statue is empty. That was Peter Norman’s request—he wanted visitors to be able to stand in his place and feel what it was like to take a stand.

In 2019, Smith and Carlos were finally inducted into the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Hall of Fame. It took 51 years. Better late than never, I guess, but it shows how long the "establishment" holds a grudge against those who disrupt the status quo.

Actionable Insights: How to Learn More

If you actually want to understand the weight of this event beyond a 1500-word article, you need to go to the primary sources. History is best served raw.

- Watch the Documentary: "The Stand" (2018) is a fantastic look at the event, featuring interviews with Smith and Carlos.

- Read the Autobiography: The John Carlos Story: The Sports Moment That Changed the World is a visceral, honest account of what he was thinking in that moment.

- Study the OPHR: Research the Olympic Project for Human Rights. Understanding their list of demands (which included the restoration of Muhammad Ali’s boxing title) shows how organized this movement actually was.

- Analyze the Photography: Look at the shots taken by John Dominis for LIFE magazine. The angles and the crowd’s reactions tell a story that words often fail to capture.

The Mexico City Olympics 1968 black power salute stands as a reminder that sports are never "just sports." They are a reflection of the world. When the world is broken, the stadium won't stay quiet. It shouldn't. Standing for something is easy when everyone is cheering. It’s a lot harder when the whole world is booing, and your career is ending before your very eyes.

The courage shown on that podium wasn't in the raised fist—it was in the willingness to accept the consequences that followed.

To truly grasp the impact of 1968, visit the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. They have an extensive exhibit dedicated to the OPHR and the protest. Additionally, look into the Peter Norman Day celebrations in Australia, which finally began to recognize his contribution to civil rights decades after his sacrifice. Understanding the fallout for all three men provides the most complete picture of why this moment remains the gold standard for athlete activism.