You’re looking up at a clear night sky. It looks empty, right? Total void. But about 31 miles up, things start getting weird. This is where the mesosphere begins. It’s the third layer of Earth’s atmosphere, sandwiched between the stratosphere and the thermosphere. Honestly, it’s the most neglected part of our sky. Scientists literally call it the "ignosphere" because it’s so hard to study.

Satellites fly too high for it. Weather balloons pop before they ever reach it. It’s this awkward middle child of the atmosphere that we’re only just beginning to understand. But here’s the thing: if the mesosphere didn't exist, life on Earth would be a relentless shooting gallery of space rocks.

Defining the Mesosphere: Where the Cold Gets Real

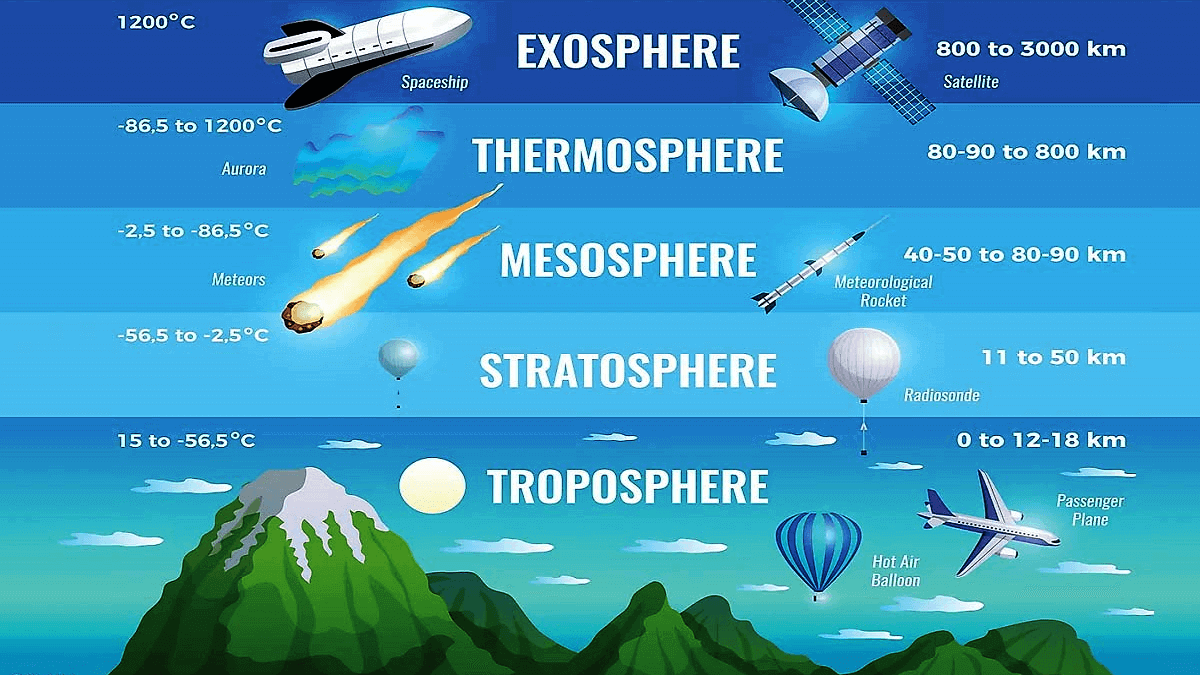

The definition of the mesosphere is pretty straightforward if you're looking at a map of the sky, but the physics are wild. It starts at the stratopause and ends at the mesopause. In terms of mileage, we're talking about the zone from 50 kilometers (31 miles) to 85 kilometers (53 miles) above the surface.

In the layer below this, the stratosphere, temperature actually goes up as you climb because the ozone layer is soaking up UV rays. But once you hit the mesosphere? The heat source is gone. Temperatures start plummeting. In fact, the top of the mesosphere is the coldest place on the entire planet. We’re talking -90°C (-130°F). Sometimes it even hits -143°C. That is colder than any recorded temperature in Antarctica.

It’s a place of extremes. The air is thin. You couldn’t breathe there, obviously. There’s not enough oxygen to keep a candle lit, let alone a human. Yet, it’s thick enough to cause friction. That friction is exactly why you see "shooting stars."

The Great Meteor Shield

Most people think meteors burn up because they hit "the atmosphere." That’s a bit vague. Specifically, they burn up in the mesosphere.

When a piece of space debris—maybe a grain of sand or a rock the size of a pebble—slams into our atmosphere at 40,000 miles per hour, it hits the gas molecules in the mesosphere. Even though the air is thin, the speed creates immense pressure and heat. The rock vaporizes. We see a streak of light.

Without this layer, these millions of daily "space dust" hits would pepper the Earth’s surface. It’s our primary line of defense. Interestingly, the vaporized meteor remains actually stay up there. They form what scientists call "meteor smoke." This smoke acts as a seeding agent for some of the strangest clouds you’ve ever seen.

Noctilucent Clouds: Electric Blue Ghosts

Have you ever seen clouds that glow in the dark? Probably not unless you live near the poles during summer. These are noctilucent clouds. They form in the mesosphere.

Because the mesosphere is so dry and cold, water vapor can only freeze if it has something to cling to. That meteor smoke provides the "dust" for ice crystals to grow. Because these clouds are so high up, they catch the sunlight from over the horizon long after the ground is dark. They look like glowing, electric blue ripples in the night sky.

NASA’s AIM (Aeronomy of Ice in the Mesosphere) mission has spent years tracking these. They’re actually becoming more frequent and appearing at lower latitudes. Some researchers, like James Russell from Hampton University, suggest this might be a "canary in the coal mine" for climate change. As methane rises into the upper atmosphere, it oxidizes into water vapor, providing more fuel for these ghostly clouds.

Why We Can't Get There

The mesosphere is a nightmare for engineers. It's often called "near space."

- Airplanes can’t fly here. The air is too thin for wings to generate lift.

- Satellites can’t orbit here. The air is too thick; the drag would pull them down and burn them up.

- It’s the "Ignosphere."

The only way we actually touch the mesosphere is with sounding rockets. These are suborbital rockets that just go up and come right back down. They spend maybe a few minutes taking measurements before gravity wins. It’s an expensive, fleeting way to do science.

Sprites and Elves: The Sky’s Secret Light Show

For decades, pilots reported seeing weird flashes of red light above thunderstorms. Most people thought they were hallucinating or seeing UFOs. It wasn’t until 1989 that researchers at the University of Minnesota accidentally captured them on film.

These are Sprites. They are massive electrical discharges—basically "upside-down lightning"—that happen in the mesosphere. They can be 30 miles wide. They look like giant red jellyfish hanging in the sky. Along with Sprites, we have "Elves" (Emission of Light and Very Low Frequency perturbations due to Electromagnetic Pulse sources). Elves are rapidly expanding rings of light that last for just one millisecond.

These phenomena prove that the mesosphere isn't just a cold, dead vacuum. It’s electrically active. It’s a bridge between our weather systems and the vacuum of space.

The Definition of the Mesosphere in a Changing Climate

While we worry about the troposphere (where we live) getting warmer, the mesosphere is doing the opposite. It’s shrinking.

As carbon dioxide increases, it traps heat near the surface. But in the thin air of the mesosphere, CO2 actually helps radiate heat out into space. This causes the upper atmosphere to cool and contract. Data from three decades of NASA satellite observations shows that the mesosphere is cooling by about 4 to 5 degrees Fahrenheit per decade.

Why does a shrinking mesosphere matter?

📖 Related: fb customer care chat: What Most People Get Wrong

It changes the drag on satellites in the layer above. If the atmosphere thins out, there’s less friction to pull old "space junk" out of orbit. This means our orbital paths stay cluttered for longer, increasing the risk of collisions. It’s a domino effect that starts with the chemistry of the mesospheric layer.

Practical Insights: How to Experience the Mesosphere

You can't go there, but you can see its handiwork.

- Watch for Meteor Showers: When you see a Perseid or Geminid meteor shower, you are literally watching the mesosphere do its job. Every flash is a high-speed collision in that specific 30-to-50-mile-high zone.

- Look for Blue at Twilight: If you are in high latitudes (like Canada, Northern Europe, or the Northern US) during the summer, look toward the horizon about 30 to 60 minutes after sunset. If you see silver-blue, wavy clouds, you're looking at the mesopause.

- Check Space Weather Reports: Sites like SpaceWeather.com often track Sprite activity. If there’s a massive thunderstorm complex (a Mesoscale Convective System) nearby, dedicated photographers often catch Sprites by filming the sky above the storm from hundreds of miles away.

The mesosphere is our planet's shield and its most mysterious frontier. It’s the place where space begins to feel like "air" and where our world ends. Understanding it isn't just for textbooks; it's about knowing how our planet handles the constant bombardment from the solar system.

To keep tabs on this layer, follow NASA's Earth Science Division updates or check the latest suborbital launch schedules from Wallops Flight Facility. They are the ones currently sending sensors into the "Ignosphere" to see what we've been missing.