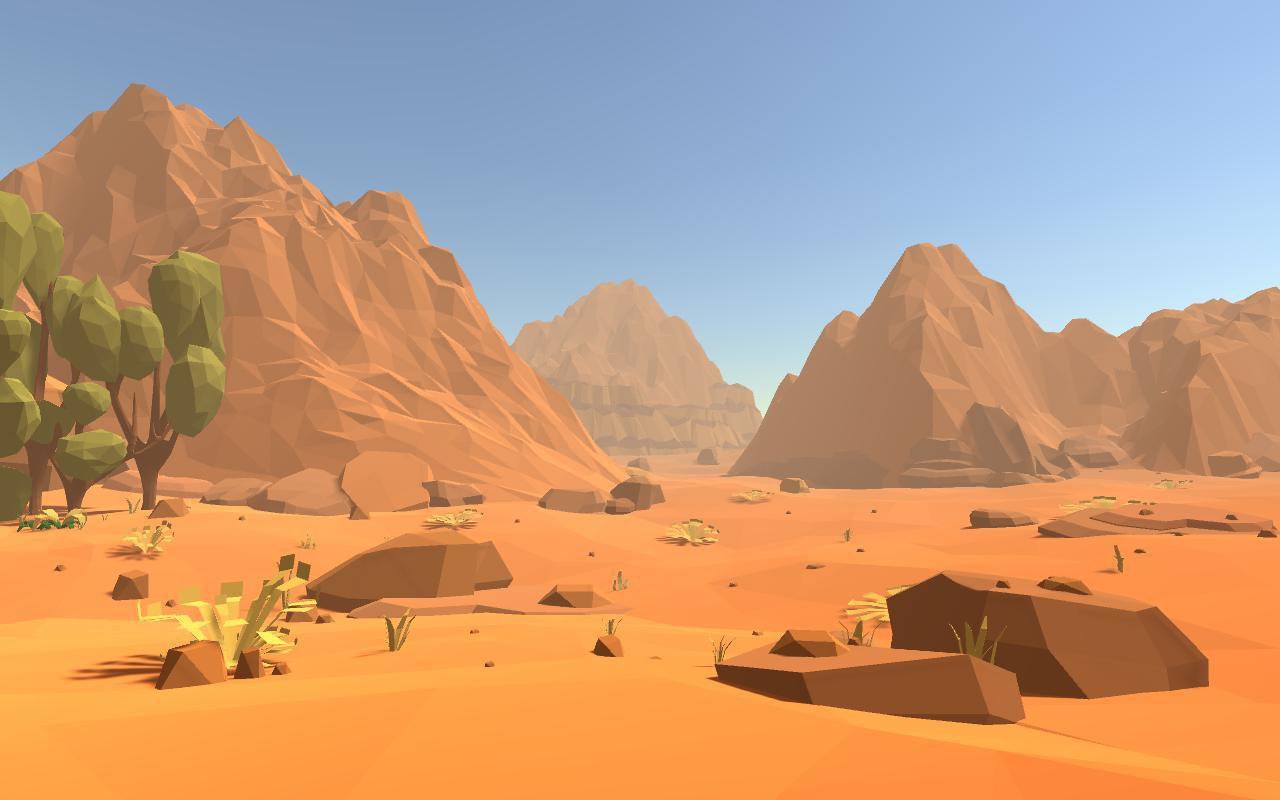

If you’ve spent any time in a sandbox game, you know the mesa biome as that rare, striped, orange-and-red wasteland where you go to find gold or terracotta. In the digital world, it’s a bit of a novelty. But mesa biome real life is actually a masterclass in geology, a story of deep time written in layers of dust and rust that spans millions of years. It’s not just "red dirt." It’s a chemical reaction. It’s a graveyard of ancient oceans.

Honestly, calling it a "biome" is a bit of a simplification from a scientific standpoint. Geologists and ecologists usually talk about badlands, plateaus, or desert scrublands when they’re looking at these formations. But the vibe remains the same. You have these massive, flat-topped hills—mesas—towering over the surrounding landscape, their sides scarred by erosion and their tops often surprisingly flat. They’re gorgeous. They’re also incredibly harsh environments that have forced plants and animals to evolve some pretty weird survival tactics.

Most people think of the American Southwest when they picture this. Places like the Colorado Plateau. You’ve got Arizona, Utah, New Mexico. But you can find these same structures in the Kimberley region of Australia or the red basins of Spain. The recipe is always the same: horizontal layers of sedimentary rock, a cap of something hard like basalt or limestone, and a lot of water and wind to tear everything else away.

How a Mesa Biome Real Life Actually Forms (It’s Messy)

Nature doesn't make things tidy. A mesa starts as a massive, elevated area of land called a plateau. Over thousands of years, water—usually from flash floods rather than steady rain—cuts through the softer layers of rock. Think of it like a giant cake. If you have soft sponge layers and a hard fondant top, the sponge is going to crumble first. In the mesa biome real life, that "fondant" is called the caprock.

The caprock is the hero here.

💡 You might also like: Where to Stay in Seoul: What Most People Get Wrong

Without a hard layer of rock on top, the whole thing would just erode into a generic hill. But because the caprock resists the wind and rain, it protects the softer shale or sandstone underneath it. Eventually, the surrounding land washes away, leaving a lonely, flat-topped mountain standing by itself. If it’s wider than it is tall, it’s a mesa. If it’s taller than it is wide, we call it a butte. If it’s just a tiny little pillar, it’s a spire. It’s basically just a scale of how much the earth has been eaten away by time.

The Chemistry of the Colors

Why the red? It’s basically rust.

Most of these landscapes are packed with iron-rich minerals. When these minerals are exposed to the atmosphere, they oxidize. Hematite gives you those deep, blood-red hues, while limonite turns things a yellowish-brown. You might even see greens or purples in places like the Painted Desert in Arizona. Those colors usually come from different oxidation states of manganese or even volcanic ash that got trapped in the mud millions of years ago.

It’s worth mentioning that these layers are literally a timeline. When you look at a mesa, you’re looking at history. The bottom layer might be 200 million years old, back when the area was a swamp filled with early dinosaurs. The top layer might be "only" 50 million years old. Dr. Marith Reheis, a researcher with the USGS, has spent years studying how dust and mineral deposits in these arid regions tell us about past climates. Every stripe in that mesa is a record of a flood, a drought, or a volcanic eruption.

📖 Related: Red Bank Battlefield Park: Why This Small Jersey Bluff Actually Changed the Revolution

Life Where Nothing Should Grow

You’d think a mesa biome real life would be a dead zone. It isn’t. But the life there is tough.

Take the pinyon-juniper woodlands that often crown the tops of these mesas. These trees are experts at living on a budget. They grow slowly. They have deep roots. They produce resin that prevents water loss. Then you have the biological soil crusts. If you ever visit a mesa, do not step on the black, crunchy dirt. That’s actually a living community of cyanobacteria, lichens, and mosses. It’s what holds the desert together. If you step on it, you’re destroying a colony that might have taken a hundred years to grow, and without it, the wind would just blow the mesa’s foundation away.

The animals are just as specialized. You’ve got the collared lizard, which looks like a miniature dinosaur and can run on its hind legs to dissipate heat. There are also bighorn sheep that navigate the sheer cliffs of mesas in Utah with terrifying ease. They use the high plateaus as a defense mechanism; not many predators can follow a sheep up a 60-degree incline of crumbling sandstone.

The Cultural Connection

We can’t talk about mesas without talking about the people who lived there first. For the Ancestral Puebloans, the mesa biome real life wasn’t just a pretty view. It was a fortress.

👉 See also: Why the Map of Colorado USA Is Way More Complicated Than a Simple Rectangle

Mesa Verde in Colorado is the most famous example. Around the 12th century, people moved from the tops of the mesas into dwellings built directly into the alcoves of the cliffs. Why? It was a genius move for climate control. The overhanging rock protected them from the brutal summer sun but allowed the lower winter sun to hit the stone and radiate heat back into the rooms at night.

These sites are fragile. The sandstone is porous. Even the oils from human hands can speed up the erosion of these ancient structures. It’s a weird irony: the very geography that protected these civilizations for centuries is now what makes their remains so hard to preserve against modern tourism.

Real Places You Can Visit

If you want to see a mesa biome real life for yourself, you have some world-class options.

- Monument Valley, Arizona/Utah: This is the "classic" look. It’s Navajo land, and the buttes here are iconic. They aren't just hills; they are sacred monuments with names like The Mittens.

- Ennedi Plateau, Chad: This is a more "off the beaten path" version. It’s in the middle of the Sahara. It has some of the most spectacular natural arches and mesas in the world, surrounded by sand instead of scrubland.

- Mount Conner, Australia: Everyone knows Uluru, but Mount Conner is a massive mesa often mistaken for it by tourists. It’s a flat-topped "artila" that towers over the desert and is part of a huge cattle station.

- The Tepuis of Venezuela: These are mesas on steroids. They are thousands of feet tall and topped with rainforests instead of deserts because of the high rainfall. They are so isolated that each one has its own unique species of plants and animals.

Why This Landscape Matters Now

Climate change is hitting these regions hard. Arid lands are getting drier. The flash floods are getting more violent. This accelerates erosion, meaning these mesas are literally disappearing faster than they used to. It might take another million years for a mesa to crumble, but the delicate ecosystems on top of them—the plants and the rare species—are much more vulnerable.

Understanding the mesa biome real life helps us understand how the Earth handles extreme stress. These are landscapes of resilience. They teach us about water management, soil conservation, and how life finds a way in the cracks of a sun-scorched rock.

Actionable Insights for Your Visit

- Check the Weather: Flash floods are the primary architect of mesas, and they are deadly. A storm ten miles away can send a wall of water through a canyon near a mesa in minutes.

- Stay on the Trail: I mentioned the biological soil crust. Seriously, "Don't Bust the Crust." It’s the difference between a healthy desert and a dust bowl.

- Timing is Everything: Mesas look flat and dull at noon. If you want to see the "Minecraft" colors pop, go at "golden hour"—the hour after sunrise or the hour before sunset. The low-angle light hits the iron oxides and makes the whole landscape look like it’s glowing from the inside.

- Bring More Water Than You Think: The air in mesa country is incredibly dry. You lose moisture just by breathing. One gallon per person per day is the standard safety rule for hikers.

- Respect Indigenous Land: Many of the world’s most famous mesas are on sacred ground. Follow local guidelines, get the right permits, and don't take "souvenir" rocks. Those rocks are the mesa’s history.