You’re standing at the seafood counter, staring at a slab of ahi tuna that looks incredible. It’s pink, marbled, and probably delicious. But then that little voice in your head starts whispering about heavy metals. You’ve seen a mercury content fish chart before—maybe on a grainy printout at the doctor's office or a frantic Facebook post—and suddenly, dinner feels like a chemistry experiment gone wrong.

It's frustrating. Seafood is supposed to be the "gold standard" of healthy protein, packed with omega-3s that keep your brain from turning into mush. Yet, we’re told some of these fish carry enough neurotoxins to make us rethink our entire diet.

Here is the truth: most people treat mercury levels like a binary "yes or no" choice. It isn’t. It’s about bioaccumulation, frequency, and—honestly—just knowing which species are the ocean’s vacuum cleaners.

Why Does a Mercury Content Fish Chart Even Exist?

Mercury isn't just "there." It’s an element, $Hg$, that occurs naturally but gets a massive boost from industrial activities like coal-burning power plants. When that mercury hits the water, bacteria convert it into methylmercury. This is the nasty stuff. It’s highly absorbable and sticks to proteins in fish tissue like glue.

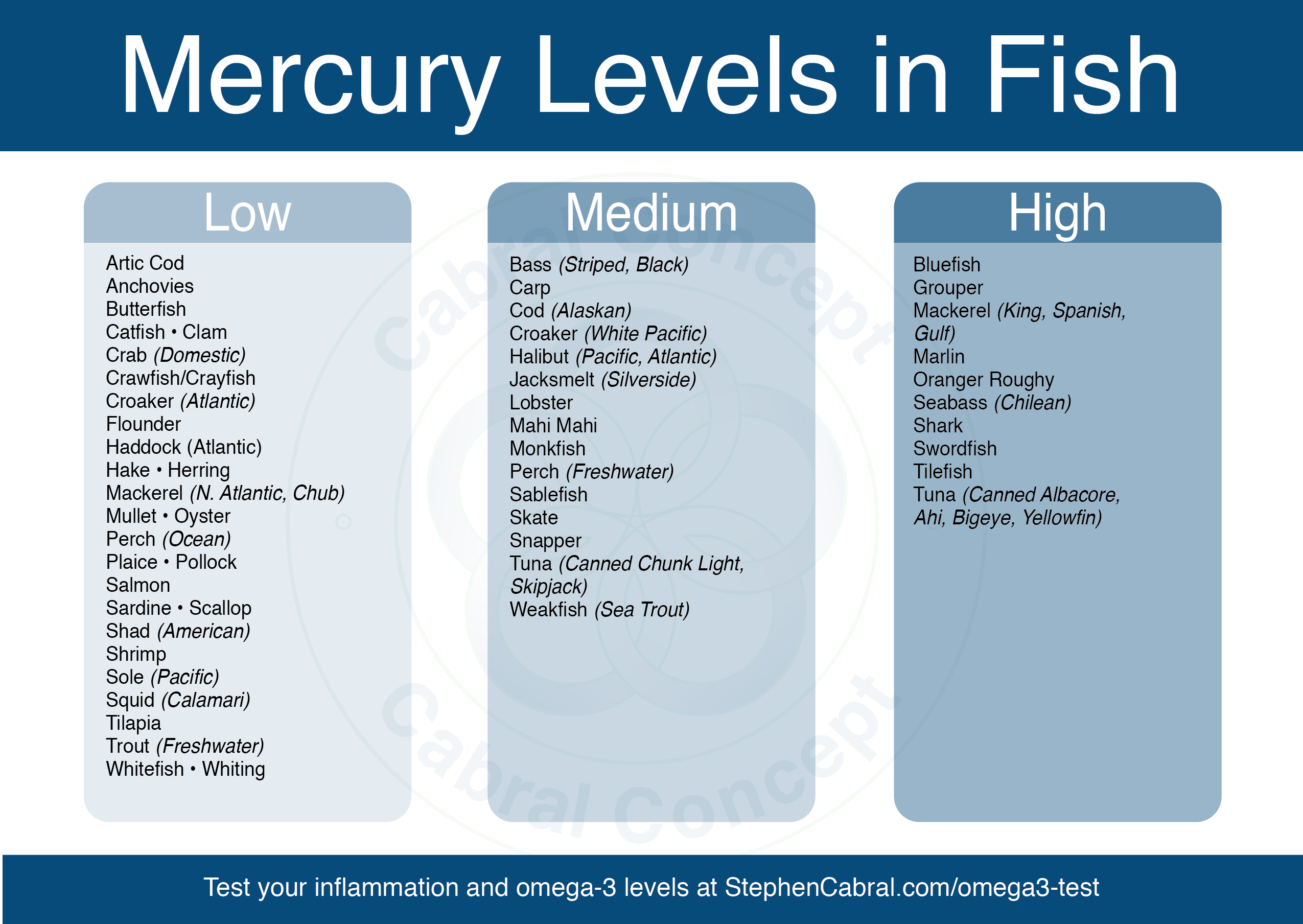

Size matters here. A tiny sardine eats some plankton. It has a microscopic amount of mercury. Then a mackerel eats ten sardines. Now it has all their mercury. Then a swordfish eats ten mackerel. You see where this is going. By the time you get to the apex predators, the concentration of mercury can be millions of times higher than the surrounding water. This is why a mercury content fish chart is usually just a map of the ocean’s food chain.

The FDA and EPA actually updated their formal advice recently, moving away from "don't eat this" toward a "Best Choices" versus "Choices to Avoid" framework. They finally realized that scaring people away from fish entirely was causing a different health crisis: a deficiency in DHA and EPA fatty acids.

The "Big Four" You Should Probably Ignore

If you look at any reputable mercury content fish chart, there are four usual suspects that consistently red-line. Honestly, if you’re pregnant, nursing, or feeding a toddler, these shouldn't even be on the menu.

- King Mackerel: Not to be confused with Atlantic or Chub mackerel, which are actually quite safe. The King is a large, predatory beast with levels often exceeding 0.7 parts per million (ppm).

- Shark: It’s chewy, it’s trendy in some circles, and it’s a mercury sponge. Because they live so long, they just keep collecting toxins.

- Swordfish: The steak of the sea. Unfortunately, it's also one of the highest in methylmercury, often averaging around 0.995 ppm.

- Tilefish (from the Gulf of Mexico): This one trips people up because Tilefish from the Atlantic is actually okay-ish, but the Gulf variety is a hard pass.

Breaking Down the "Safe" Zones

Most of what we eat falls into the middle or low categories. This is where the nuance lives. Take tuna, for example. You can't just say "tuna is high in mercury." That's lazy.

Canned light tuna (usually skipjack) is significantly lower in mercury than Albacore or "White" tuna. Specifically, skipjack usually hovers around 0.12 ppm, while Albacore can be three times that. If you're using a mercury content fish chart to plan your weekly meal prep, you can safely eat skipjack two or three times a week, but you should probably limit Albacore to once a week.

💡 You might also like: TEAS Exam Practice Questions: What Most People Get Wrong

Then you have the "Best Choices." These are the heroes of the seafood world.

- Salmon (Wild or Farmed): Remarkably low mercury and high fat.

- Sardines and Anchovies: These fish live fast and die young. They don't have time to accumulate toxins.

- Shrimp and Scallops: Most shellfish are bottom feeders, but they don't bioaccumulate methylmercury in their muscle tissue the same way finfish do.

- Trout: Specifically freshwater trout, which is a fantastic alternative to salmon.

The Selenium Factor: The Secret Buffer

Here is something most "expert" articles miss: Selenium.

Research from Dr. Nicholas Ralston at the University of North Dakota has shown that selenium—an essential mineral found in many fish—actually binds to mercury and neutralizes its toxicity. If a fish has more selenium than mercury, the risk to your brain is significantly mitigated. This is why ocean-going fish like Yellowfin tuna, despite having moderate mercury, rarely cause issues in populations that eat them traditionally; they are loaded with selenium.

The only fish that consistently have more mercury than selenium are the "Big Four" mentioned earlier. That's a huge distinction that your average infographic won't tell you.

How Much is Too Much?

The EPA sets a "Reference Dose" (RfD), which is basically an estimate of daily exposure that is likely to be without an appreciable risk of deleterious effects during a lifetime. For methylmercury, that’s $0.1$ micrograms per kilogram of body weight per day.

If you're a 150-pound adult, that means you can safely handle about 7 micrograms of mercury daily. A 6-ounce serving of high-mercury swordfish might contain 150 micrograms. You do the math. You’d be blowing your "budget" for three weeks in a single dinner.

On the flip side, 6 ounces of salmon might only have 2 or 3 micrograms. You could eat that every single day and never come close to the safety limit. This is why the mercury content fish chart shouldn't scare you away from the fish counter; it should just guide you toward the smaller, oilier options.

Practical Steps for Seafood Lovers

Stop overthinking it and follow a few basic rules to keep your heavy metal intake low while keeping your heart healthy.

👉 See also: Trying 3 People Yoga Poses Without Hurting Your Friends

- Size down your species. Swap your tuna steaks for salmon or Arctic char.

- Check the "Best Choices" list. The current FDA guidelines list over 30 types of fish that are safe to eat 2-3 times per week, including catfish, cod, flounder, and tilapia.

- Eat variety. Don't be the person who eats canned tuna every single day for lunch. That's how you end up with "accidental" mercury poisoning. Rotate your proteins.

- Pay attention to local advisories. If you're catching fish in local lakes or streams, the national mercury content fish chart doesn't apply. Runoff from old mines or local factories can make even "safe" species dangerous. Always check your state's Department of Natural Resources (DNR) website.

- Prioritize the SMASH fish. Sardines, Mackerel (Atlantic), Anchovies, Salmon, and Herring. These are the nutritional powerhouses with the lowest toxic load.

Managing mercury isn't about avoidance; it's about intelligence. Most of the fish in the sea are perfectly safe and incredibly good for you. Use the data as a filter, not a barrier. When you choose smaller fish and diversify your plate, the benefits of those omega-3s far outweigh the trace amounts of metals you might encounter. Focus on the "Best Choices" category for 80% of your intake, and treat the high-mercury stuff like an occasional luxury rather than a dietary staple.