Dan O'Bannon was broke. He was sleeping on a friend's couch, his previous project Dune had collapsed in France, and he was basically obsessed with the idea of something living inside a human body. That’s the messy, unglamorous reality of memory: the origins of alien. It wasn't some corporate masterplan. It was a collection of nightmares, stolen ideas, and a script originally titled Star Beast that felt, honestly, a little bit B-movie at first.

If you look back at the 1970s, sci-fi was either bright and optimistic like Star Wars or cold and clinical like 2001: A Space Odyssey. Nobody was doing "truckers in space." But O'Bannon and his writing partner Ronald Shusett wanted to make a movie about biological violation. They wanted to scare people in a way they hadn't been scared before. They pulled from a deep well of collective memory: the origins of alien aren't found in a single source, but in a weird mix of 1950s creature features and the high-concept art of the underground.

The Script That Refused to Die

O'Bannon had this specific memory of a "gremlin" on a B-17 bomber from an old story. He took that concept and pushed it into the future. Shusett was the one who solved the biggest plot hole: how does the creature get on the ship? He suggested the "facehugger" concept. The idea was to have the alien implant its offspring inside a human host. It was a complete subversion of traditional horror tropes. Usually, the "final girl" or the victim is female, but here, the violation was directed at a man, Kane.

When the script landed at Brandywine Productions, Walter Hill and David Giler weren't immediately sold on the sci-fi elements, but they loved the pacing. They added the "Android" subplot—the character of Ash—which O'Bannon actually hated at first. He thought it cluttered the story. History proved him wrong. That addition added a layer of corporate coldness that makes the film feel so modern today. It's funny how the best parts of a masterpiece are often the things the original creator fought against.

✨ Don't miss: Priyanka Chopra Latest Movies: Why Her 2026 Slate Is Riskier Than You Think

The Swiss Nightmare: Enter H.R. Giger

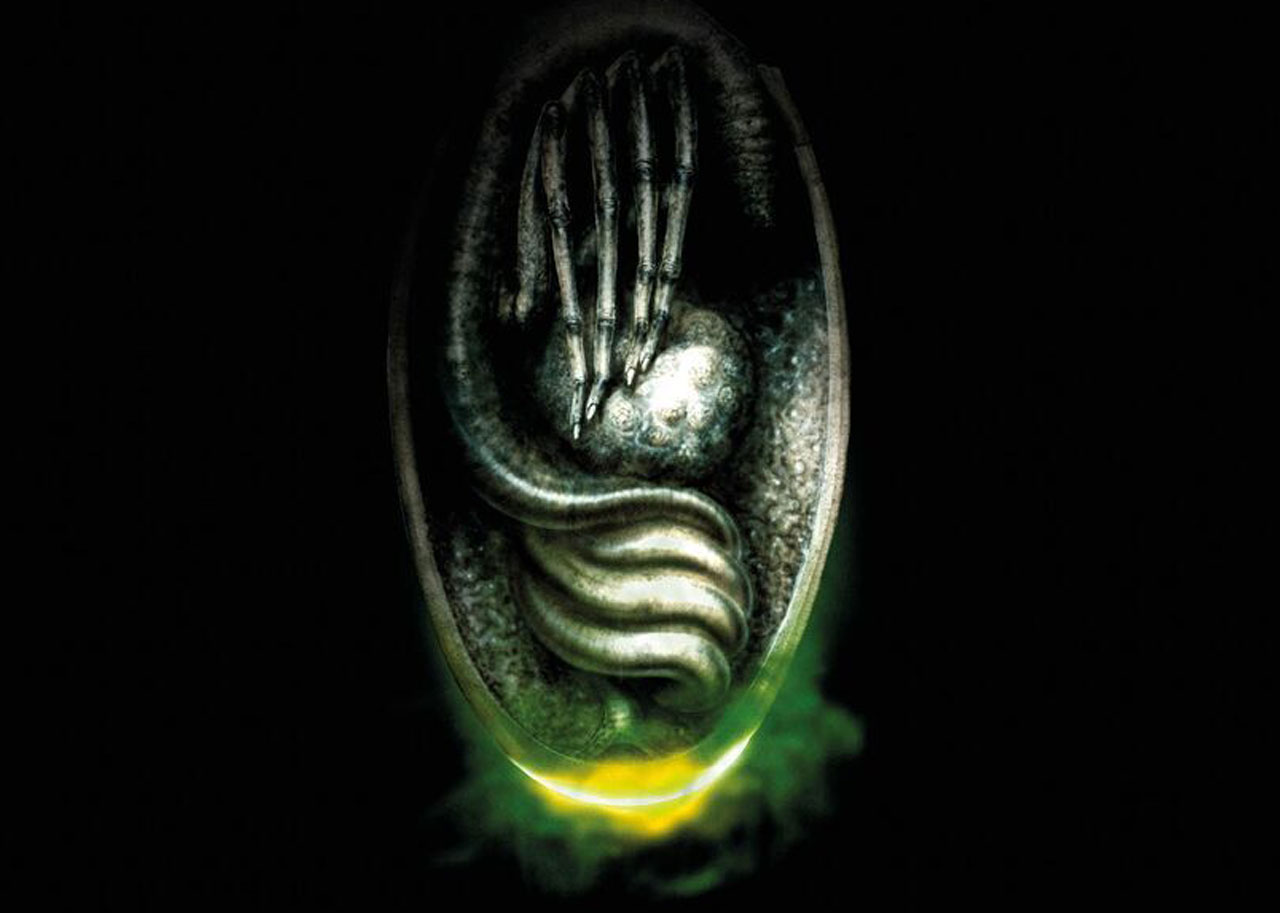

You can't talk about memory: the origins of alien without mentioning the Necronomicon. Ridley Scott saw H.R. Giger’s art book and basically knew the movie was made or broken by that man’s imagination. Giger’s work was "biomechanical." It looked like bone, pipe, and flesh all fused together. It was deeply sexual and deeply upsetting.

Fox executives were terrified of Giger’s designs. They thought it was too much for a mainstream audience. They were probably right, but Scott pushed through anyway. Giger didn't just draw the monster; he built it. He used real human skulls for the head of the Xenomorph. He used condoms for the translucent tendons in the jaw. This wasn't some guy in a rubber suit; it was a physical manifestation of a nightmare that felt uncomfortably real.

Ridley Scott’s Visual Memory

Scott came from a background in commercials. He was a visual perfectionist. He didn't want the Nostromo to look like a spaceship from a movie; he wanted it to look like a refinery. Dirty. Gritty. Used. This "used universe" aesthetic was pioneered by Lucas, but Scott took it to a dark, industrial extreme.

🔗 Read more: Why This Is How We Roll FGL Is Still The Song That Defines Modern Country

- The lighting was often done with handheld flashlights.

- The sets were cramped, causing actual claustrophobia among the cast.

- The actors weren't told exactly what the "Chestburster" scene would look like.

When John Hurt’s chest exploded and the fake blood sprayed Veronica Cartwright, her scream was 100% genuine. She didn't know the blood would hit her face. That’s not just acting; that’s a captured moment of pure shock. It’s a memory etched into cinema history because it bypassed the "acting" and went straight to the lizard brain.

Why It Still Works

Most horror movies age poorly. The effects look cheesy or the scares become predictable. Alien doesn't. Why? Because it taps into primal fears: the fear of the dark, the fear of being eaten, and the fear of pregnancy gone wrong. It’s a biological horror film.

The Xenomorph itself has no eyes. Think about that. You can’t look it in the eye to find a spark of humanity or a soul. It’s just a killing machine. It’s a "perfect organism," as Ash says. The contrast between the cold, calculating nature of the robot and the raw, acidic hunger of the alien creates this pincer movement of terror. You’re trapped between a corporation that views you as "expendable" and a monster that views you as meat.

💡 You might also like: The Real Story Behind I Can Do Bad All by Myself: From Stage to Screen

The Legacy of the Nostromo

The impact on the industry was seismic. Before 1979, sci-fi was often seen as "kids' stuff." Alien changed the demographic. It proved that you could have a high-budget, beautifully shot film that was also a visceral slasher movie.

- Sigourney Weaver as Ripley: She wasn't the lead in the original script. The characters were written to be interchangeable regarding gender. By casting Weaver, they created the greatest female action hero in history without ever making it about her being a woman. She was just the most competent person on the ship.

- Sound Design: The silence of space is a trope now, but the way Alien uses ambient noise—the humming of the ship, the dripping of water, the heartbeat—is a masterclass in tension.

- The Slow Burn: The monster doesn't even fully appear until late in the movie. It’s all about the buildup.

Looking back at memory: the origins of alien, we see a perfect storm of talent. You had O'Bannon’s paranoia, Giger’s surrealism, and Scott’s visual eye. If any one of those people hadn't been there, the movie would have been a forgettable 70s flick. Instead, it’s a foundational text of the genre.

Moving Beyond the Nostromo

If you want to truly appreciate how this film came together, you should look into the documentary Memory: The Origins of Alien by Alexandre O. Philippe. It dives deep into the mythological roots of the story, connecting the Xenomorph to the Furies of Greek myth. It’s not just a movie; it’s an exploration of the dark side of the human psyche.

Actionable Insights for Fans and Creators

To understand the DNA of this masterpiece, focus on these three elements:

- Study the Biomechanical: Look at H.R. Giger’s early work in the book Necronomicon. It explains why the alien looks "organic" yet "mechanical," a key reason it still feels alien today.

- Embrace the "Used Future": If you are a writer or artist, remember that realism comes from wear and tear. The Nostromo feels real because it looks like a place where people actually work and sweat.

- Subvert Biology: The most effective horror often comes from twisting natural processes (like birth or growth) into something unrecognizable.

To get the full experience, watch the 1979 theatrical cut first. Avoid the "Director's Cut" for your first viewing—Scott himself has said the original theatrical pacing is actually his preferred version. Pay attention to the silence. In an era of loud, CGI-heavy blockbusters, the quiet moments in Alien are where the real terror lives.