Everyone knows the Achilles heel thing. We've seen Brad Pitt brood on a beach in Troy, and we've all sat through those long high school lectures about Hector and the big wooden horse. But honestly, most of us have been getting the Trojan War wrong—or at least, we've only been seeing half the map.

There is a massive, gaping hole in the story we usually tell.

🔗 Read more: Will There Be a Now You See Me 3? What’s Actually Happening Behind the Scenes

A new play titled Memnon just blew the doors off the traditional Greek mythos, first at the Getty Villa in Los Angeles and most recently with the Classical Theatre of Harlem. It isn't just another "swords and sandals" reboot. It’s a restoration of a character who was once considered the equal of Achilles himself, yet somehow got scrubbed from the popular Western imagination for about a thousand years.

Who Was the "Other" King at Troy?

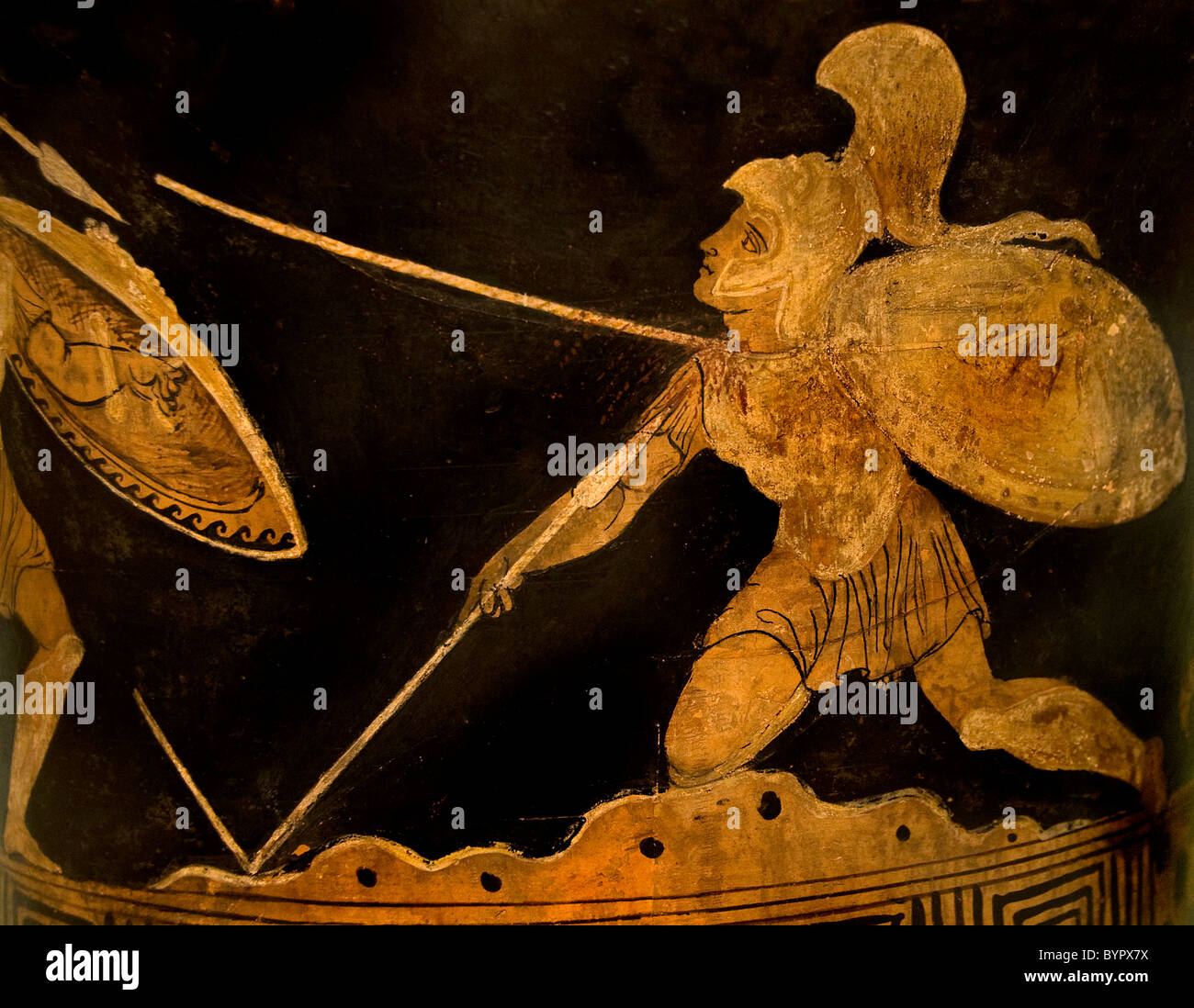

Basically, Memnon was the King of Ethiopia. In the ancient world, he wasn't some minor footnote; he was a demigod, the son of Eos (the Goddess of the Dawn). When Hector fell and Troy was basically circling the drain, King Priam didn't look to the local neighbors for a savior. He looked south.

He called in the big guns from Africa.

The play, written by Will Power and directed by Carl Cofield, introduces us to a warrior who is weary. He's tired. Memnon, played with a sort of magnetic, heavy-hearted intensity by Eric Berryman, isn't a mindless killing machine. He is a man who actually left Troy years ago because he felt like an outsider—"kin and not kin," as the script puts it.

Imagine being the nephew of the King of Troy but being treated like a second-class citizen because of your heritage. You'd probably move to Ethiopia and start your own kingdom, too.

But then the call comes. Troy is burning.

Why This Story Was "Lost"

You've gotta wonder why we don't hear about this guy in The Iliad. Well, Homer actually does mention him, but only briefly. There was an entire epic poem called the Aethiopis that focused on Memnon, but it was lost to time. Gone. Like a corrupted hard drive from 700 BC.

Sophocles even wrote a play about him. That’s lost, too.

What Will Power has done with Memnon: new play about the trojan war is essentially a daring act of literary forensics. He used iambic hexameter—a rhythmic, driving verse that feels ancient and modern at the same time—to reconstruct a story that should have stayed in the canon.

It’s a bit of a gut punch to realize how much of history we’ve collectively "forgotten" because it didn't fit a specific Eurocentric narrative.

The Tension You Won't Find in Textbooks

The drama in this play isn't just about who can swing a spear better. It's about the "double-dealing" of King Priam (played by Jesse J. Perez). Priam is depicted as a bit of a "twit" in a laurel crown—desperate enough to beg for Memnon’s help but still bigoted enough to refer to him dismissively as "The African" when he thinks nobody is listening.

It’s messy. It’s uncomfortable. It’s also very real.

Helen of Troy (Andrea Patterson) gets a much-needed makeover here, too. She isn't just a "face that launched a thousand ships." She’s a woman trapped in a political nightmare who sees in Memnon a kindred spirit—someone else who is "of Troy" but never truly accepted by it.

- The Conflict: Memnon has to decide if a city that rejected him is worth dying for.

- The Combat: When he finally squares off against Achilles (Jesse Corbin), it’s not just a fight; it’s a "lethal ballet" choreographed by Tiffany Rea-Fisher.

- The Cost: No spoilers, but this is a Greek tragedy. Things don't usually end with everyone grabbing drinks afterward.

The production uses this wild mix of broken classical columns and metal scaffolding. It looks like a construction site for a civilization that’s actively falling apart. It’s a perfect metaphor for the way the characters are trying to build an identity out of the rubble of their own trauma.

Why Memnon Matters in 2026

We are currently in an era where we're obsessed with "origin stories." We want to know the "why" behind the hero.

🔗 Read more: Brant von Hoffman: What Most People Get Wrong About the 80s Character Actor

Memnon hits that nerve perfectly because it addresses the feeling of "belonging and kind of belonging." It talks about the "haves and the have-nots." Honestly, listening to Memnon talk about being a "nation sliced apart" feels less like a dispatch from the Bronze Age and more like a commentary on the morning news.

The play clocks in at about 75 minutes—no intermission. It’s fast. It’s lean. It doesn't waste time on fluff.

The movement is heavy on the influence of EMERGE125, the dance company involved in the production. Sometimes the ensemble moves like a "ghostly army," and it adds this eerie, supernatural layer to the mud and blood of the Trojan trenches.

Actionable Insights for Theater Lovers and History Buffs

If you’re interested in seeing how history is being rewritten in real-time, here is what you should do:

- Look for the Classical Theatre of Harlem's touring schedule. This play has already moved from the West Coast to NYC (Marcus Garvey Park), and there’s a high chance it will continue to hit major regional theaters given the critical acclaim.

- Read up on the "Epic Cycle." Most people only know the Iliad and the Odyssey. Look into the summaries of the lost poems like the Aethiopis. It changes your entire perspective on the scale of the Trojan War.

- Support "Neoclassical" Work. Playwrights like Will Power are doing the heavy lifting of diversifying the classics. If you like this, check out his other work like Seize the King.

- Visit the Getty Villa or Marcus Garvey Park. Both venues offer a unique "open-air" experience that mimics how these plays were originally seen under the sun and stars.

Ultimately, Memnon isn't just a "new play about the Trojan War." It’s a correction. It reminds us that Troy was a global conflict involving empires that spanned continents.

History isn't just what was written down and saved; it’s also what we choose to remember.

Next Steps: Check the official Classical Theatre of Harlem website for their upcoming 2026 season announcements, as they often bring back successful neoclassical works for limited engagements or national tours.