It was 1977. Most people in the music industry thought Jim Steinman and Meat Loaf were out of their minds. They had this bloated, operatic, Wagnerian rock project called Bat Out of Hell that every single major label had already rejected. Clive Davis famously told Steinman he didn't know how to write songs. But then there was meatloaf 2 out 3 aint bad, a track that felt just a little more "normal" than the rest of the madness. It saved the record.

Honestly, it’s the most "radio-friendly" thing they ever did together, even if it still feels like a mini-drama.

The song didn't come from a place of grand artistic vision. It came from a dare. Actress Mimi Kennedy, a friend of Steinman’s, told him he should try writing something simple for once. Something like an Elvis Presley song. Steinman, being the maximalist he was, couldn't just do "simple." He sat down and tried to write a standard love ballad, but his brain wouldn't let him leave it at "I love you." He had to add that devastating, cynical twist: I want you, I need you, but there ain't no way I'm ever gonna love you.

Why the Irony Worked

Most love songs are binary. You either love the person or you’ve lost them. This song occupies the messy, uncomfortable middle ground where a lot of real relationships actually live. It’s about being "good enough" for the night but never being "the one."

Meat Loaf’s vocal performance here is surprisingly restrained. If you listen to "Paradise by the Dashboard Light," he’s screaming, panting, and theatrical. On meatloaf 2 out 3 aint bad, he sounds vulnerable. He sounds like a guy sitting at a kitchen table at 3:00 AM trying to be honest with someone he’s about to hurt. That contrast is exactly why the song resonated with the public. It reached number 11 on the Billboard Hot 100, which, for a guy who looked like a sweating linebacker in a tuxedo, was a massive achievement in the disco era.

✨ Don't miss: Who was the voice of Yoda? The real story behind the Jedi Master

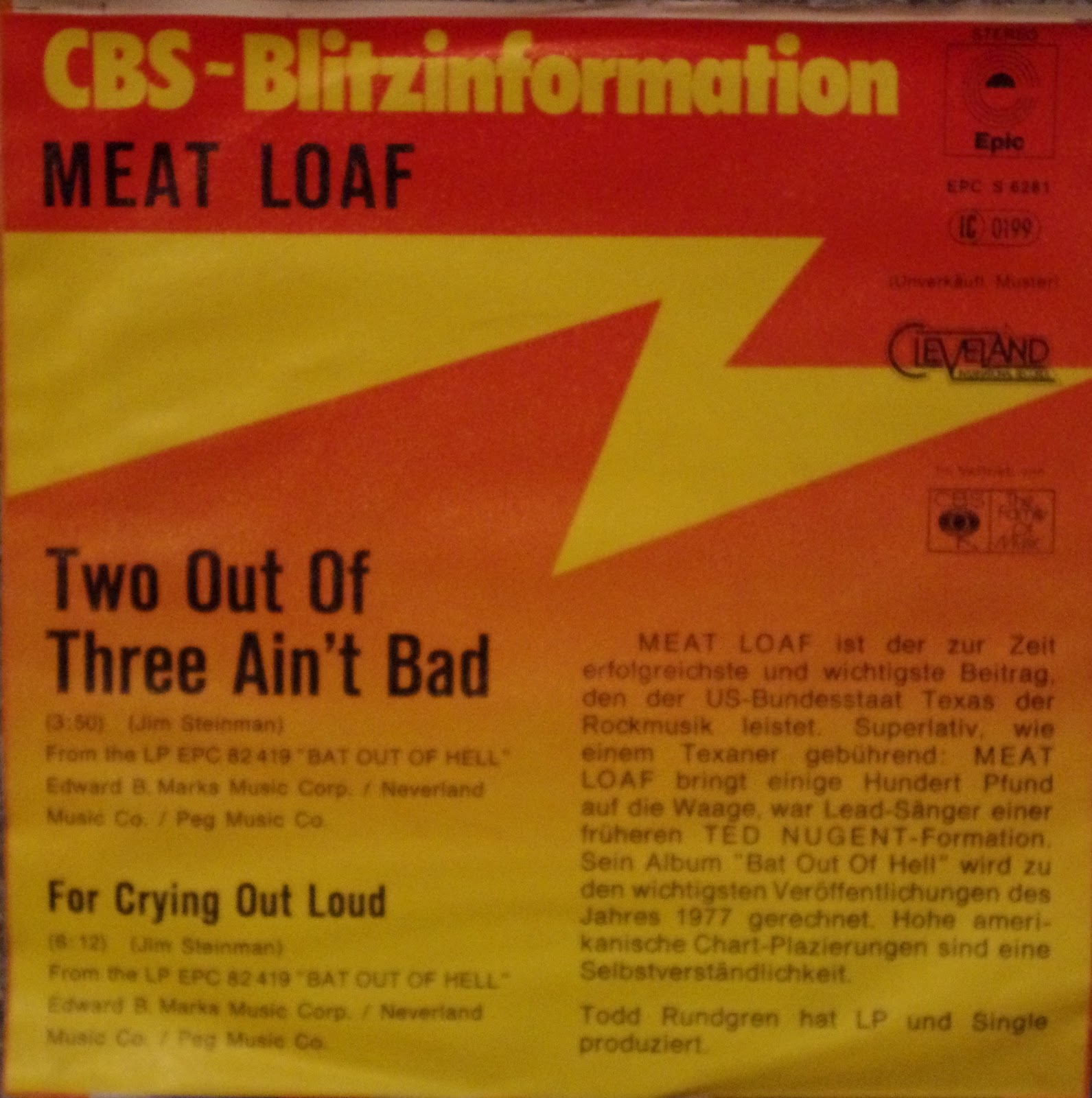

Todd Rundgren, who produced the album, deserves a lot of the credit for the sound. He famously thought the album was a parody of Bruce Springsteen and Phil Spector. Because he thought it was a joke, he leaned into the tropes of 1950s balladry. He played the guitar parts himself, and those lush, soaring strings were actually Rundgren playing a keyboard called a Mellotron. It gave the track a "timeless" feel that helped it bypass the specific trends of the late 70s.

The Statistical Reality of a Slow Burn

When we talk about Bat Out of Hell, we’re talking about one of the best-selling albums in history. We're talking 43 million copies. But it didn't start that way.

The album sold almost nothing in its first few months. It was the release of meatloaf 2 out 3 aint bad as a single that finally gave DJs something they could play without scaring off their audience. Once that song started climbing the charts, people went back and discovered the rest of the operatic insanity on the record. It was the "gateway drug" for the Meat Loaf phenomenon.

Interestingly, the song has an almost country-music structure. Steinman was a fan of the way country lyrics told a story with a punchline at the end of the chorus. He took that Nashville sensibility and wrapped it in a New York rock-and-roll production. If you stripped away the piano and the swelling backing vocals, you could easily imagine George Jones singing these lyrics.

🔗 Read more: Not the Nine O'Clock News: Why the Satirical Giant Still Matters

The Song’s Legacy and Cultural Weight

People still get the lyrics wrong at weddings. It’s funny, really. You’ll hear it played during a slow dance, and you have to wonder if the couple is actually listening to what the guy is saying. He is literally telling the woman that she’s a silver medal.

The song was certified Gold by the RIAA in 1978. That’s 500,000 physical copies of a single. In an era where streaming has diluted the value of a "hit," it's hard to explain how ubiquitous this song was on FM radio. It stayed on the charts for months. It became the template for every power ballad that would dominate the 1980s. Without this track, you probably don't get the career of Bonnie Tyler or the later power-ballad era of Cher. Steinman proved that you could be "theatrical" and "pop" at the same time.

Some critics at the time hated it. Dave Marsh of Rolling Stone was notoriously unkind to Meat Loaf. They thought it was overblown. But the fans didn't care. The fans saw a guy who didn't look like a rock star singing about feelings that felt more real than the polished disco tracks on the other stations.

What Most People Miss About the Lyrics

There is a specific line in meatloaf 2 out 3 aint bad that reveals the whole story: "I read it in a magazine, next to a picture of Billy Queen."

💡 You might also like: New Movies in Theatre: What Most People Get Wrong About This Month's Picks

Who is Billy Queen? He wasn't a real person. Steinman made him up to represent the "perfect" guy—the rock star, the icon, the guy the girl in the song is actually crying over. The narrator knows he can't compete with a ghost or a celebrity crush. He’s basically saying, "I’m real, I’m here, but I’m not him." It’s a song about the inadequacy we feel when we aren't someone's first choice.

Actionable Takeaways for Music Fans and Collectors

If you're looking to dive deeper into this specific era of rock history, there are a few things you should actually do rather than just reading about it.

- Listen to the "Live at Rockpalast" version from 1978. You can find it on various DVD releases or YouTube. It shows Meat Loaf at his absolute physical peak. You can see the sweat and the desperation that made the recorded version feel so authentic.

- Compare it to "It's All Coming Back to Me Now." If you want to see how Jim Steinman evolved the "2 Out of 3" formula, listen to the Celine Dion version of his later work. You'll hear the same DNA—the same buildup, the same cynical romanticism—but with 90s production values.

- Check the vinyl dead wax. If you are a collector, look for the original Cleveland International/Epic pressings. Some of the early promo copies have a slightly different mix that highlights the backing vocals by Ellen Foley and Rory Dodd more than the standard radio edit.

- Read "Little by Little" by Meat Loaf. His autobiography gives a gritty, non-sanitized look at the recording sessions at Bearsville Studios. He talks openly about how he struggled with the low-key nature of this specific song because he wanted to "belt" everything.

- Analyze the "Jim Steinman" irony. If you're a songwriter, study the "A-B-C-Twist" structure of the chorus. Steinman sets up two positives (I want you, I need you) and subverts them with a negative (I’m never gonna love you). It’s a classic songwriting trick that still works today to keep listeners engaged.

The song remains a staple of classic rock radio for a reason. It isn't just nostalgia. It’s a masterclass in how to write a "commercial" song without losing your weird, artistic soul. Steinman and Meat Loaf might have been outliers in the 70s, but they proved that if you give people a good enough melody, they’ll let you tell them the most heartbreaking, cynical truths imaginable.