If you’ve ever sat through a high school history lecture or scrolled through a digital archive of the 1860s, you’ve seen them. Those haunting, high-contrast images of men in wool coats leaning against cannons, or the more gruesome shots of "The Dead of Antietam" sprawled across the grass like discarded ragdolls. Usually, the caption says something simple: Mathew Brady Civil War photos.

It’s a name that carries a lot of weight. We’re told Brady was the "Father of Photojournalism." We’re told he risked his life to bring the "terrible reality" of war to the doorsteps of New York.

But here’s the thing. Most of the stuff you think you know about those photos is, honestly, kind of a myth.

The Man Behind the Legend (Who Rarely Held the Camera)

Brady was a rockstar in his day. He was the guy who photographed Abraham Lincoln so well that Lincoln basically credited the portrait for his presidency. But when the Civil War broke out, Brady didn't just grab a camera and run toward the sound of the guns. He was an entrepreneur. A brand.

By the time the war started in 1861, his eyesight was already failing. He was nearly blind.

Because of this, Brady rarely operated the camera himself on the battlefield. Think of him more like a movie director or a studio head than a solo photographer. He hired a massive team—around 20 men—and sent them out into the mud with horse-drawn wagons that doubled as darkrooms. These wagons were called "What-is-it?" wagons by the soldiers because they looked so bizarre.

The Hidden Names

If Brady wasn't the one clicking the shutter, who was?

- Alexander Gardner: This guy was a genius with the "wet-plate" process. Most of the famous shots of Lincoln and the aftermath of Antietam were actually his.

- Timothy O’Sullivan: He later became famous for photographing the American West, but during the war, he was one of Brady's top field guys.

- James Gibson: Another name lost to the shadow of the "Brady" brand.

Brady had this habit of putting his own name on everything. Every plate, every print. It didn't matter if Gardner or O’Sullivan spent three days in a swamp to get the shot; the credit line always read: Photograph by Brady.

🔗 Read more: Why the Chef and the Frog Still Haunts Our Kitchen Dreams

Eventually, this ego trip caused a massive rift. Gardner got sick of the lack of credit and quit in 1863 to start his own rival studio. He even took some of Brady's best photographers with him.

Why the Photos Feel So... Still

Have you ever wondered why there aren't any actual "action shots" in Mathew Brady Civil War photos? You see the "before" and the "after," but never the "during."

It wasn't a choice. It was a technical limitation.

Photography back then used the wet-plate collodion process. Basically, a photographer had to coat a glass plate with chemicals, rush it into the camera while it was still wet, expose it, and then rush it back to the wagon to develop it before the chemicals dried. If the plate dried out, the image was ruined.

Exposure times were long. Seconds, sometimes nearly a minute. If a soldier moved his head to swat a fly, he turned into a blurry ghost. If a regiment charged, they vanished from the frame.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Christian Dior Junon Dress is Still the Most Famous Gown in Fashion History

This is why the photos are so weirdly quiet. They show the exhaustion of the camp, the stillness of the dead, and the wreckage of Richmond. They couldn't capture the chaos, so they captured the silence.

The Exhibition That Shocked Manhattan

In October 1862, Brady did something that changed American culture forever. He opened an exhibition in his New York gallery called "The Dead of Antietam."

Up until that point, war was seen as something "noble" and "glorious." It was something you read about in poems or saw in sanitized paintings. But Brady (via Gardner’s lens) showed the public bodies piled up in trenches. He showed the bloated faces of young men left in the sun.

The New York Times wrote a review that still hits hard today. They said Brady hadn't brought the bodies to the door-yards of the city, but he had done "something very like it."

People were horrified. They were also obsessed. They lined up around the block to see the carnage. It was the first time in history that a civilian population saw the reality of a war while it was still being fought.

A Financial Disaster

You’d think a guy this famous would be set for life. Not even close.

Brady spent a literal fortune—over $100,000—funding his war project. He assumed the U.S. government would buy the collection for a massive sum once the war ended.

He was wrong.

After the war, nobody wanted to look at photos of dead soldiers anymore. The country wanted to move on. The government refused to buy the plates. Brady spiraled into debt. He was forced to sell his New York studio. In 1875, Congress finally threw him a bone and paid him $25,000 for the collection, but it wasn't enough to cover his debts.

He died in 1896, penniless, in a charity ward of a hospital. He was basically forgotten until decades later when historians realized that without his "impresario" spirit, we wouldn't have a visual record of the war at all.

Exploring the Archives Today

If you want to dive into the actual Mathew Brady Civil War photos, don't just look at the famous ones. The National Archives and the Library of Congress have digitized over 6,000 of these images.

What to Look For

- The Background Details: Look past the generals. Look at the trash in the camps, the makeshift stoves, and the expressions on the faces of the "Contrabands" (formerly enslaved people who sought refuge with the Union Army).

- Stereographs: Many of these were taken with double-lensed cameras. When viewed through a "stereoscope," they appeared in 3D. It was the VR of the 1860s.

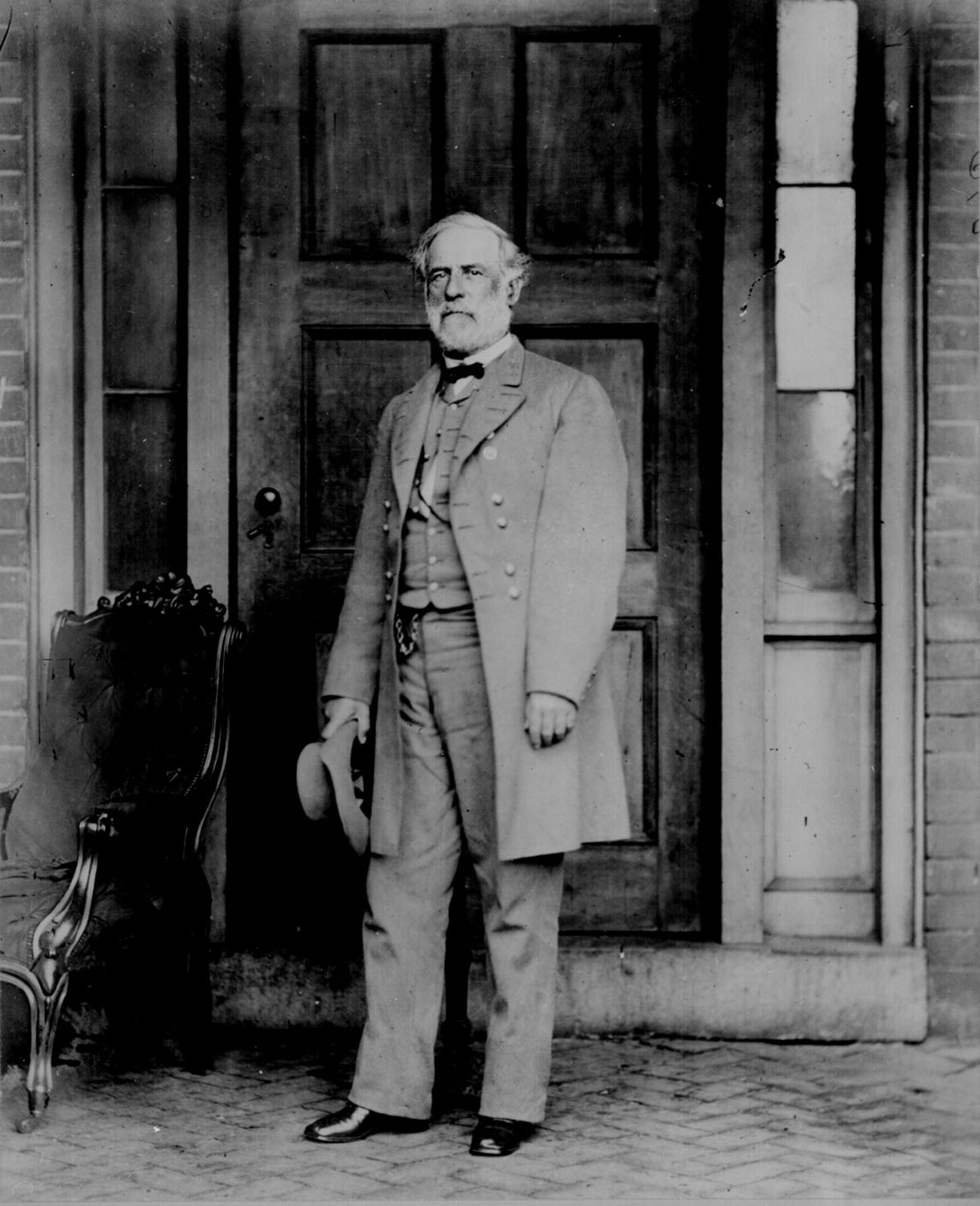

- The "Brady" Cameo: Sometimes you can spot a man with a goatee and a straw hat in the distance of a photo. That’s usually Brady himself, inserting himself into the history he was "directing."

Actionable Next Steps

If you’re a history buff or a photography nerd, here’s how to actually use this information:

- Check the Metadata: When looking at an "original" Brady photo on the Library of Congress website, look for the "Creator" field. You’ll often see names like Alexander Gardner or Timothy O'Sullivan listed. Give them the credit Brady wouldn't.

- Visit the National Portrait Gallery: If you’re ever in D.C., they have a permanent collection of Brady’s work. Seeing the actual glass plates—some of which still have cracks from being moved across battlefields—is a completely different experience than seeing a JPG.

- Search for "The Dead of Antietam": Look specifically for the 1862 series. Pay attention to how the bodies are positioned; there’s some evidence that photographers occasionally "arranged" scenes for more dramatic effect, which is a whole other rabbit hole of ethics in early journalism.

The legacy of Mathew Brady Civil War photos isn't just about the war itself. It's about the moment we stopped imagining what history looked like and started actually seeing it. Even if the man behind the name wasn't always the one holding the camera.