It is a heavy realization. We like to think of modern hospitals as the great equalizers, places where the best technology and the brightest minds ensure every mother goes home with a healthy baby. But the data says something else entirely. If you look at the numbers, having a baby in the United States is statistically more dangerous than it is in almost any other wealthy nation. And honestly? If you are a Black or Indigenous woman, the risk profile changes so drastically it looks like you’re living in a different century. Maternal mortality by race isn't just a clinical statistic; it’s a mirror reflecting deep-seated failures in how we provide care.

Let’s get into the weeds.

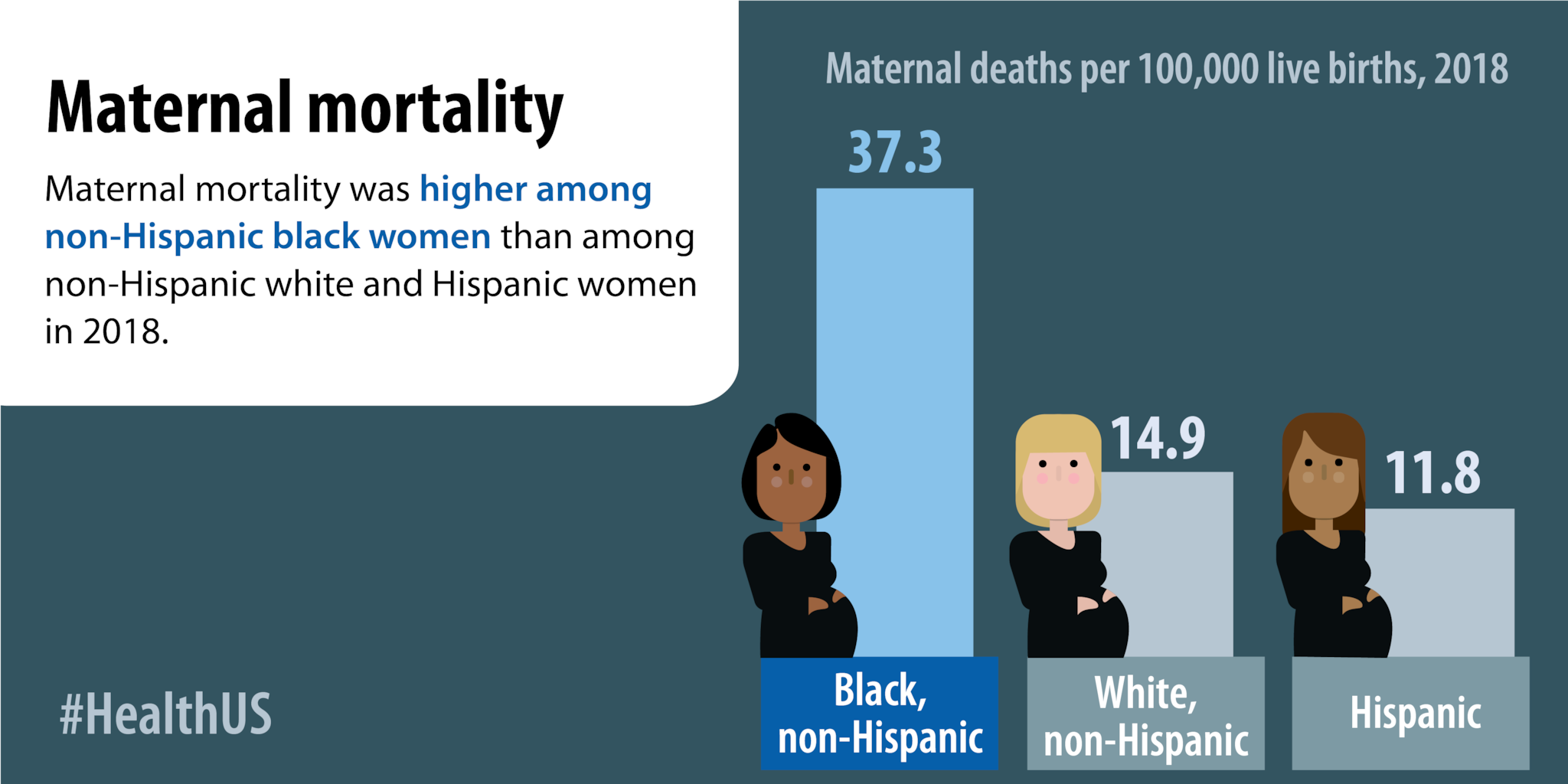

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Black women are roughly three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than White women. We aren't talking about a slight deviation or a statistical fluke. We are talking about 69.9 deaths per 100,000 live births for Black women compared to 26.6 for White women, based on 2021 figures. It’s staggering. Even when you account for income, education, and access to prenatal care, the gap persists. A wealthy Black woman with a master’s degree is still more likely to die from childbirth-related complications than a White woman who didn't finish high school. That tells us the issue isn't just about money or "lifestyle choices." It’s something systemic.

Why the gap in maternal mortality by race is widening

People often assume these deaths happen on the delivery table in a burst of sudden drama. They don't. Most of them happen in the days and weeks after the baby is born. Think about that. A woman goes home, feels "off," calls her doctor, and is told it's just the "normal" exhaustion of new motherhood. But for many women of color, that "normal" exhaustion is actually a pulmonary embolism or skyrocketing blood pressure from preeclampsia.

The CDC’s Maternal Mortality Review Committees (MMRCs) have found that over 80% of these deaths are preventable. That is the part that should keep you up at night. Eight out of ten women who die didn't have to.

📖 Related: Why That Reddit Blackhead on Nose That Won’t Pop Might Not Actually Be a Blackhead

Weathering and the biological toll of stress

Dr. Arline Geronimus, a professor at the University of Michigan, coined a term for this: "weathering." It’s the idea that the chronic stress of living in a marginalized body—dealing with discrimination, microaggressions, and socioeconomic hurdles—literally ages the body's systems faster. Your heart, your lungs, and your kidneys are under constant pressure. By the time a woman is 30, her biological age might be 40. When you add the massive physical toll of pregnancy onto a body that is already "weathered," the system snaps. It’s not a personal failing. It’s a physiological response to an environment that is constantly pushing back against you.

Implicit bias in the exam room

We have to talk about how doctors listen—or don't listen. Serena Williams, arguably the greatest athlete of all time, almost died after giving birth to her daughter. She had a history of blood clots. She felt the symptoms. She told her medical team what she needed. They hesitated. If a woman with her resources and fame struggles to be heard, what happens to the woman without a platform?

Studies consistently show that Black patients are perceived as having a higher pain tolerance or being less compliant. This isn't usually "mustache-twirling" villainy from doctors. It’s implicit bias. It’s the split-second decisions made in a crowded ER where a provider relies on stereotypes instead of the person in front of them. When a patient says "I can't breathe" or "My head feels like it's exploding," and the provider dismisses it as anxiety, that's where the tragedy starts.

The Indigenous experience: A forgotten crisis

While the conversation often focuses on the Black-White gap, American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) women face equally harrowing odds. They are twice as likely to die from pregnancy-related causes as White women. Much of this is tied to the geographic isolation of many tribal lands. If you live two hours away from a hospital that has an OB-GYN, a postpartum hemorrhage isn't just a complication—it’s a death sentence.

👉 See also: Egg Supplement Facts: Why Powdered Yolks Are Actually Taking Over

The Indian Health Service (IHS) has been chronically underfunded for decades. Facilities are often outdated. Staff turnover is high. When you lose the "continuity of care"—meaning you see a different doctor every time—important red flags get missed.

Breaking down the leading causes of death

It’s not just one thing. It’s a cluster of conditions that hit different groups with varying intensity.

- Mental Health Conditions: This is actually the leading cause of pregnancy-related deaths overall, including suicide and overdose related to substance use disorder.

- Hemorrhage: Severe bleeding. It’s often preventable if the hospital has a "hemorrhage cart" and a strict protocol for weighing blood loss instead of just "eyeballing" it.

- Cardiac and Coronary Conditions: This is where the racial gap is most pronounced. Black women are much more likely to suffer from peripartum cardiomyopathy—a form of heart failure.

- Infection and Sepsis: Often occurring in the postpartum period when the mother is no longer under constant observation.

The policy failure and the "MomsBus"

For a long time, Medicaid—which covers nearly half of all births in the U.S.—only provided postpartum coverage for 60 days. Think about that. You have a major surgery or a grueling physical event, and 61 days later, you’re on your own. No more blood pressure checks. No more mental health support.

Thankfully, things are changing. As of 2024, the vast majority of states have opted to extend Medicaid postpartum coverage to a full year. This is massive. It gives doctors a window to catch the late-onset complications that kill so many. Representative Lauren Underwood and the "Black Maternal Health Caucus" have been pushing the Momnibus Act, a series of bills designed to fund community-based organizations, improve data collection, and diversify the perinatal workforce.

✨ Don't miss: Is Tap Water Okay to Drink? The Messy Truth About Your Kitchen Faucet

What "good" care actually looks like

If you want to see what works, look at doulas. A doula isn't a doctor; they are a support person. But the data shows that having a doula—especially one from your own community—significantly lowers the risk of C-sections and complications. They act as a bridge. They help the mother navigate the medical jargon and, crucially, they advocate for her when she’s too tired to advocate for herself.

We also need to look at the "Midwifery Model of Care." In countries like Sweden or Japan, midwives handle the majority of low-risk births. In the U.S., we over-medicalize everything. When we integrate midwives into the hospital system, outcomes tend to improve because midwives are trained to watch for the subtle, early signs that something is going wrong before it becomes a 3-alarm fire.

Moving beyond the statistics

It’s easy to get lost in the "why" and forget the "who." Behind every number is a family that was destroyed. A child growing up without a mother. A partner trying to figure out how to be a single parent while grieving.

The medical community is starting to wake up. We are seeing more "implicit bias training," though its effectiveness is still being debated. We are seeing hospitals implement "safety bundles"—standardized checklists for things like preeclampsia—so that every patient gets the same level of care regardless of what they look like or what insurance they have. But training isn't enough. We need a fundamental shift in how we value women's lives, particularly the lives of women of color.

Actionable steps for safer outcomes

If you are pregnant or planning to be, especially if you fall into a high-risk demographic, you aren't powerless. Knowledge is a protective layer, even if it shouldn't have to be your responsibility alone.

- Find a "Mom-Friendly" Hospital: Look for facilities that have the "Blue Distinction Center" for maternity care or those that publicly share their racial equity data.

- The "Postpartum Warning Signs" List: Memorize it. If you have a severe headache that won't go away, vision changes, swelling in your legs, or an overwhelming sense of doom, go to the ER. Don't call the clinic and wait for a call back. Go.

- Bring an Advocate: Whether it’s a partner, a mother, or a professional doula, never go into a birth or a postpartum checkup alone. You need someone who is not in pain and not exhausted to speak up.

- The "Power of Why": If a doctor denies a test or a treatment you asked for, say: "I’d like you to document in my chart exactly why you are refusing this specific request." It’s amazing how quickly the tone changes when there is a paper trail.

- Check Your Insurance: If you are on Medicaid, confirm your state has the 12-month postpartum extension. If not, start looking for local community health centers that offer sliding-scale follow-up care.

The crisis of maternal mortality by race won't be fixed overnight by a single policy. It requires a complete overhaul of how we listen to women. It’s about ensuring that the joy of a new life isn't overshadowed by a preventable tragedy. We have the tools. We have the data. Now we just need the collective will to treat every birth with the urgency it deserves.