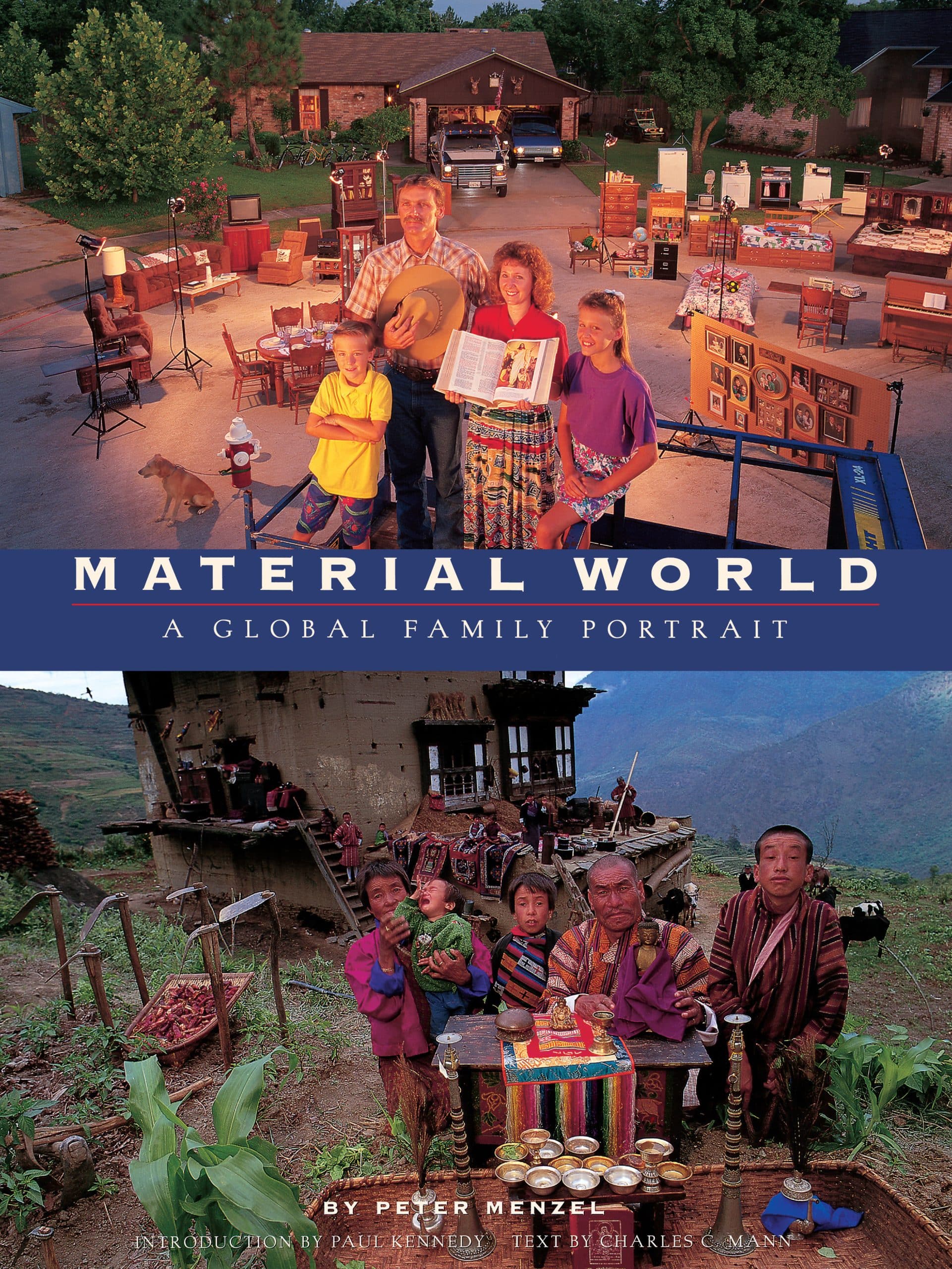

In 1994, a photographer named Peter Menzel did something that sounds simple but was actually a logistical nightmare. He asked families around the globe to do one thing: drag every single possession they owned out into the street or yard and pose for a portrait with it. The result was Material World A Global Family Portrait, a book that basically slapped us in the face with the reality of how we live. Honestly, looking at these photos today feels even weirder than it did back then. We’re living in an era of digital clutter, but Menzel’s work captured the physical weight of our lives before the internet changed how we consume stuff.

It wasn't just about the "stuff," though.

It was about the people. The project featured 30 statistically "average" families from 30 different countries. You had the Wu family in China, the Natomos in Mali, and the Kapnivos in South Africa. Each photo is a dense, visual data set. You can spend an hour looking at a single image, counting the bags of grain or the number of plastic chairs, and realize you're learning more about global economics than you ever did in a textbook.

The Chaos Behind the Camera

People think these shots were just quick "point and click" moments. They weren't. Imagine trying to convince a family in a rural village—or a high-rise in Tokyo—to move their beds, stoves, icons, and even their livestock out of the house just for a photo. Menzel and his team of 16 photographers spent weeks with these families. They lived with them. They ate their food.

There's this one story about the Paukas in Iceland. To get that shot, they had to deal with freezing winds and the sheer mass of a modern Western household. Contrast that with the Namgay family in Bhutan, who lived in a beautiful, three-story farmhouse but had relatively few "things" to move. The sheer physical labor involved in creating Material World A Global Family Portrait mirrors the physical labor of the lives depicted.

What the Data Actually Told Us

When you look at the United States family—the Skenes from Texas—the sheer volume of items is overwhelming. They’ve got the big fridge, the multiple cars, the electronics. Then you flip the page to the Natomo family in Mali. Their most prized possessions were a few pots, some grain sacks, and their livestock.

The book included a "Statistically Average" breakdown for each country. It listed things like:

💡 You might also like: Bootcut Pants for Men: Why the 70s Silhouette is Making a Massive Comeback

- Life expectancy

- Annual income (in 1990s USD)

- The primary source of energy

- The number of children per household

But the photos told the truth that the numbers couldn't reach. They showed the pride in a mother’s face as she sat near her sewing machine—a tool for survival—versus the somewhat buried look of a family surrounded by toys and gadgets they probably forgot they owned.

Why We Are Still Obsessed With These Photos

Basically, we're voyeurs. We love seeing how other people live. But Material World A Global Family Portrait tapped into a deeper curiosity about fairness. It’s impossible to look at these images without playing the "Comparison Game." You look at your own living room and wonder, If I had to drag all this onto the lawn, how long would it take? Would I be embarrassed by how much I have? Or worse: Would I realize I have nothing of actual value?

The book arrived at a specific turning point in history. The Cold War had just ended. Globalism was the new buzzword. We were told the whole world was becoming one big marketplace. Menzel showed us that while the marketplace might be global, the distribution of its goods was—and still is—wildly, almost violently, unequal.

The "Average" Trap

One thing people get wrong about this project is thinking these are the "poorest" or "richest" people. Nope. The photographers worked with sociologists to find families that were "statistically average" for their specific nation. That’s what makes it so haunting. The family in India wasn't a caricature of poverty; they were a representation of the median. When you see the gap between the median in Kuwait versus the median in Haiti, the reality of the "Global North" versus the "Global South" stops being an abstract concept and becomes a physical pile of chairs and rugs.

The Technological Shift: 1994 vs. 2026

If you did this project today, the photos would look completely different. In 1994, a family's wealth was visible. You could see the stereo system, the stacks of CDs, the encyclopedias, and the heavy CRT television.

Today? Most of that has been sucked into a six-inch slab of glass and aluminum in our pockets.

📖 Related: Bondage and Being Tied Up: A Realistic Look at Safety, Psychology, and Why People Do It

A modern Material World A Global Family Portrait would actually look "emptier" for the middle class in developed nations, despite us owning more than ever. We’ve traded physical objects for digital subscriptions. But for the families in the developing world, the "stuff" still matters. A sturdy roof, a reliable cookstove, and clean water containers are still the gold standard of wealth.

I think about the Yadev family in India often. In the original photo, their possessions were modest but functional. Today, they’d almost certainly have smartphones. The digital divide has narrowed, even if the wealth gap has widened like a canyon.

Forgotten Details of the Project

Most people just remember the big "pile of stuff" photos, but the book actually went deeper. It asked each family a series of standardized questions.

- What is your most valued possession? (Often religious items or tools for work).

- What are your hopes for your children? (Almost universally: education and a better life).

- What is the one thing you want that you don't have?

These answers provided the soul of the book. It wasn't just a catalog of consumerism. It was a study in human desire. Honestly, it’s kind of heartbreaking to see that whether you're in a yurt in Mongolia or a suburb in Illinois, everyone basically wants the same three things: safety, a future for their kids, and maybe a slightly better way to get around.

The Logistics of the "Shot"

Photographer Miguel Luis Fairbanks, who worked on the project, talked about the difficulty of the "sky-down" perspective. They often had to use cherry pickers or climb onto roofs to get the wide angle needed to fit a whole life into one frame. There was no Photoshop to "stitch" images together back then. If the light changed or it started raining, the whole day was ruined. You can't just tell a family to put their entire life back inside and "try again tomorrow."

The tension in some of the families' faces isn't just because they're posing; it’s the literal stress of having their private lives exposed to the neighborhood.

👉 See also: Blue Tabby Maine Coon: What Most People Get Wrong About This Striking Coat

How to Use the Lessons of "Material World" Today

We talk a lot about minimalism now. YouTubers tell us to get rid of everything that doesn't "spark joy." But looking at Material World A Global Family Portrait puts that trend into perspective. Minimalism is a luxury of the over-provided.

For many of the families in Menzel's book, every single item had to spark joy, or at least utility, because there was no room for waste.

If you want to apply the insights from this project to your own life, stop looking at your stuff as "decor" and start looking at it as "resources." Here is how you can practically re-evaluate your own "Global Portrait":

- The Mobility Test: If you had to move every item you own into your yard in four hours, what would you leave behind? That’s your true "clutter."

- The Utility Ratio: Look at the Natomo family (Mali) and their grain bags. Everything they owned supported their survival. Look at your own "pile." What percentage of your stuff actually supports your life, and what percentage just demands your time to clean or organize it?

- Acknowledge the Ghost Items: We own things that aren't there. Software, cloud storage, debt. These are part of our "Material World" now, even if they don't show up in a photograph. They weigh us down just as much as a heavy wardrobe.

The brilliance of Menzel’s work is that it doesn't judge. It just records. It shows the Skene family in Texas with their huge truck and the Calabay family in Guatemala with their corn—and it lets you decide which life looks more "balanced." It’s a mirror.

Most of the children in those 1994 photos are now in their 30s or 40s. They are living in a world that is more connected but somehow feels more cluttered. The "portrait" of the world is no longer just on our lawns; it’s on our screens, 24/7. But the physical reality of what we need to survive—food, shelter, and a few things that remind us of who we are—hasn't changed one bit.

To truly understand your place in the world, go find a copy of this book. Don't just scroll through the highlights online. Sit with the pages. Look at the dirt on the ground, the texture of the walls, and the expressions in the eyes of the people. It’s the closest thing we have to a time capsule of the human soul at the end of the 20th century.

Your Practical Next Steps:

- Audit Your Essentials: Identify the five physical objects in your home that are actually essential for your daily survival or livelihood.

- Contextualize Your Wealth: Use a global wealth calculator to see where your household income sits relative to the rest of the world; it’s usually a wake-up call.

- Document Your Own World: Take one photo of your most-used room exactly as it is—no cleaning up—to see what your "average" really looks like.