Drawing a "B" seems like the easiest thing in the world until you actually sit down with a brush pen or a piece of charcoal and try to make it look professional. Most of us learned the "ball and stick" method in kindergarten. You draw a vertical line, you slap two semi-circles on the side, and you're done. Except, if you’re trying to do typography, graffiti, or even just clean architectural lettering, that basic approach is exactly why your work looks amateurish.

Letters have weight. They have gravity.

🔗 Read more: AutoZone on Wilson Way: What You Actually Need to Know Before Heading In

When you look at a typeface like Helvetica or even a classic serif like Times New Roman, the "B" isn't symmetrical. If you draw the top loop the same size as the bottom loop, the letter will actually look top-heavy. It’s an optical illusion. Our eyes perceive the bottom of objects as needing to be wider to support the weight of the top. If you want to learn how to draw B like a pro, you have to start by unlearning your elementary school handwriting.

The Anatomy of a Perfect B

Before you put pen to paper, you need to understand the "waistline." In typography, this is often near the x-height. For a capital B, the junction where the two bowls meet should actually be slightly above the vertical center.

Think about it.

If the middle bar is dead center, the top hole (the counter) looks huge. Professional sign painters, like the legendary John Downer, often emphasize that the "optical center" is higher than the geometric center. You’ve got to trick the eye.

The vertical stroke is called the stem. In most styles, this is your anchor. If you're doing calligraphy, this is usually a downstroke, meaning it’s thick. The curves, or "bowls," are where people usually mess up. They try to make them perfect circles. Real letters are rarely perfect circles; they are ovals or "squircled" shapes that flow into the stem.

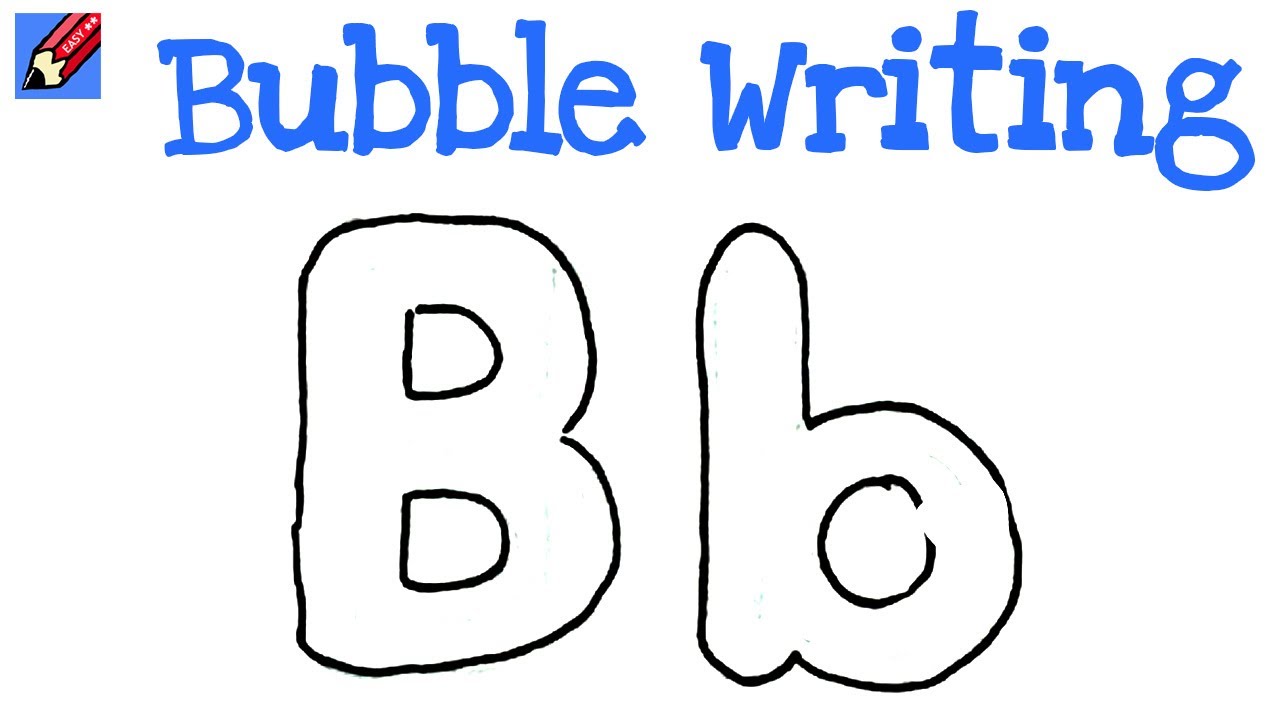

Lowercase vs. Uppercase Dynamics

The lowercase "b" is a different beast entirely. It’s an ascender letter. You have the tall stem (the ascender) and then a single bowl at the bottom. The biggest mistake here? Not "tucking" the bowl into the stem correctly.

If you just attach a circle to a line, you get a "tangent" that looks weak. You want the curve to emerge naturally from the vertical line. In high-end typography, the stroke often thins out right before it hits the stem to avoid a big blob of ink. This is called "thinned joins." It’s a tiny detail, but it’s the difference between a logo and a doodle.

Step-by-Step: The Professional Construction

Let's get tactile. Grab a pencil—preferably something soft like a 2B or 4B so you can feel the paper.

- Start with your vertical stem. Keep it straight, but don't use a ruler yet. You want to train your hand.

- Mark your halfway point. Now, move that mark up about 2 millimeters. This is your new center.

- Draw the top bowl. It should be slightly narrower and shorter than the bottom one.

- Draw the bottom bowl. Let it sweep out a bit further to the right. This gives the letter "stature."

Actually, let's talk about the "overlap." In many classic Roman styles, the top bowl actually finishes its curve inside the start of the bottom bowl. It’s not two separate humps. It’s a continuous flow where the bottom curve starts slightly recessed. It creates a sense of elegance.

Style Variations That Actually Matter

If you’re drawing for a specific vibe, the "B" changes everything.

Graffiti Style: Here, the "B" is all about the "kick." Writers often exaggerate the bottom bowl so much that it overlaps other letters. They might add a "serif" or a "chip" to the top left of the stem. It’s about movement. Use "bars" instead of single lines. Think of the letter as a 3D object with thickness.

Block Lettering: This is what you see on college sweatshirts. Everything is squared off. The secret to a good block "B" is the internal corners. If the outside is a sharp 45-degree angle, the inside "counter" should also be angled. Don't mix round insides with square outsides. It looks weird.

Script and Calligraphy: This is where pressure comes in. If you’re using a brush pen, you press down on the stem (thick) and ease up as you go around the loops (thin). The "join" in the middle of the B is usually a very thin hair-line.

Common Pitfalls (And How to Fix Them)

Honestly, the "flat back" is the biggest killer. When people draw the bowls, they often make them too flat where they meet the stem. It makes the letter look like it’s collapsing. You want a "branching" effect. Imagine a tree branch growing out of a trunk. It doesn't just stick out at a 90-degree angle; it curves out.

👉 See also: The Lamb of God Hymn: Why This Ancient Song Still Hits So Hard Today

Another thing: the counters. The white space inside the "B" is just as important as the black ink. If the top hole is a different shape than the bottom hole (beyond just size), the letter feels "broken." They should feel like siblings, not strangers.

Actionable Tips for Better Lettering

Stop practicing on blank paper. It's a trap. Use graph paper or dot grid paper. This forces you to see the proportions.

- Ghosting: Before you touch the paper, move your pen in the air in the shape of the B. It builds muscle memory.

- The Upside Down Test: Once you finish your B, turn the paper upside down. If the bottom (now the top) looks ridiculously huge, you didn't compensate enough for the optical illusion.

- Negative Space Focus: Instead of drawing the letter, try drawing the two "holes" inside the B. If the holes look right, the letter will naturally follow.

Refining your technique takes time, but focusing on the "waistline" and the "branching" of the bowls will immediately set your work apart from someone just "writing" the letter. Start practicing by drawing the letter B at a large scale—about 3 inches tall. It reveals every flaw in your curves and forces you to control your steady hand. Once you master the B, you’ve basically mastered the P, R, and D, as they all share the same structural DNA.

Focus on the weight distribution. Keep the bottom heavy, the middle high, and the joins clean. That’s how you turn a simple character into a piece of art.