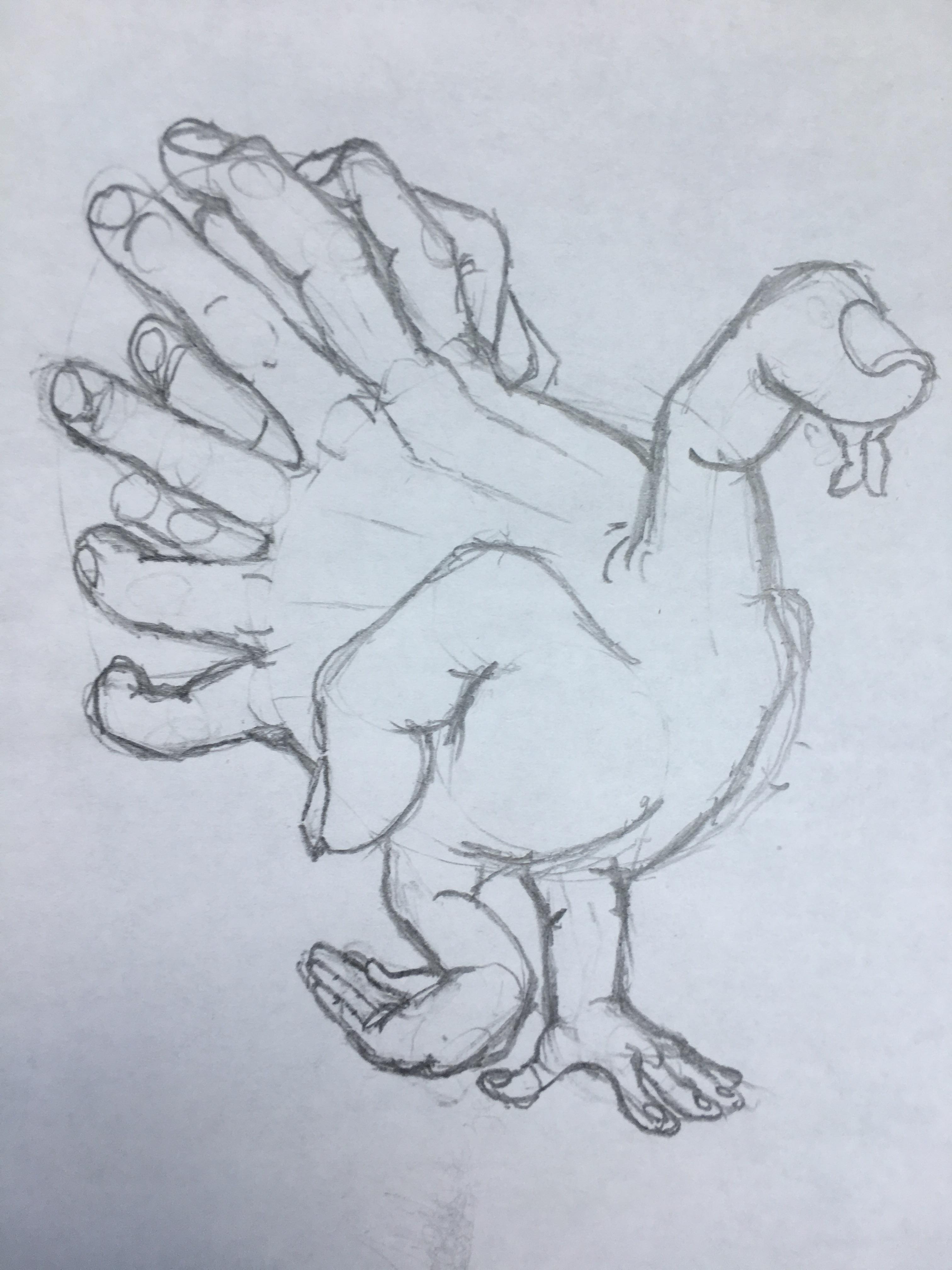

You’ve done it. I’ve done it. Pretty much every kid in an American classroom since the mid-20th century has sat down, pressed their palm against a piece of cheap construction paper, and traced the outline of their own hand to create a "turkey." It’s a rite of passage. But honestly? Most of those drawings look less like a Meleagris gallopavo and more like a strange, five-fingered fleshy fan.

If you're looking to move past the kindergarten tracing and actually tackle a real hand drawing of turkey anatomy, you have to look at what's actually happening under those feathers. It’s not just about drawing a circle for a body and some sticks for legs.

Real turkeys are weird. They are bulky, ground-dwelling birds with iridescent feathers that change color depending on how the light hits them. Their heads are bumpy and colorful. Their "beards" are actually modified feathers that feel like horsehair. When you approach a hand drawing of turkey, whether you’re using graphite, charcoal, or digital brushes, you’re basically trying to map out a series of overlapping textures. It’s a challenge of volume versus detail.

The Tracing Trap and How to Escape It

The classic hand-trace turkey is a cultural icon, sure. But it teaches us zero about actual avian structure. In a real hand drawing of turkey, the "fingers" of the bird—the tail feathers—don't just stick out from the top of the head. They fan out from the uropygium, which is the fleshy mound at the base of the tail.

If you want to make your drawing look like it belongs in a field guide rather than on a refrigerator, start with the skeletal structure. Or at least the gesture. Turkeys have a heavy, pear-shaped body. The center of gravity is low. When they walk, they have this rhythmic, almost mechanical bob. You have to capture that weight. If the body looks too light, the bird looks like a pigeon. Turkeys are the tanks of the bird world.

Think about the "snood." That’s the fleshy bit that hangs over the beak. It changes size. Seriously. When a male turkey (a tom) is excited or trying to impress a hen, that snood can elongate until it dangles way past the beak. In a hand drawing of turkey, getting the texture of the caruncles—the fleshy bumps on the neck—is what separates the amateurs from the pros. Use small, overlapping "C" shapes to build that texture. Don't just draw dots. Dots look like chickenpox. You want it to look like rugose skin.

📖 Related: Is there actually a legal age to stay home alone? What parents need to know

Understanding the Tail Fan

The fan is the star of the show. If you’re drawing a Tom in full strut, you’re dealing with 18 tail feathers. Usually. Evolution isn't always perfect, so some birds might have a few more or less, but 18 is the standard for a healthy wild turkey.

When you start your hand drawing of turkey tail, don't draw the feathers as flat planks. They overlap like a deck of cards spread in a semi-circle. Each feather has a dark band near the tip, often followed by a lighter "terminal" band. If you get those bands wrong, the whole perspective falls apart. The light should hit the top of the fan, while the feathers closer to the body stay in deep shadow.

Materials Matter More Than You Think

I’ve seen people try to do a detailed hand drawing of turkey using a standard HB pencil and printer paper. It’s a nightmare. The paper is too smooth; it won't hold the layers.

- Toned Paper: Use tan or gray paper. Since turkeys have so many mid-tones and highlights, starting with a neutral base lets you use a white charcoal pencil for the highlights on the feathers.

- Kneaded Erasers: You aren't just erasing mistakes. You're "drawing" with the eraser to create the thin, light shafts of the feathers (the rachis).

- Blending Stumps: Use these sparingly. If you over-blend, the turkey will look like it’s made of plastic. You need that crisp, "toothy" texture of the feathers to remain visible.

Honestly, the best way to practice is to look at the work of David Allen Sibley. His "The Sibley Guide to Birds" is the gold standard for bird illustration. He doesn't just draw what he sees; he draws what he knows about the bird's anatomy. When you look at his turkey illustrations, you can see the distinction between the primary wing feathers and the secondary ones.

Lighting the Iridescence

This is the hardest part of any hand drawing of turkey. A wild turkey isn't just brown. It’s bronze, gold, green, and copper. In a graphite drawing, you have to translate color into value. The parts of the bird that are "green" might actually be a lighter gray in your drawing, while the "bronze" sections are darker.

👉 See also: The Long Haired Russian Cat Explained: Why the Siberian is Basically a Living Legend

If you're working in color—maybe colored pencils or pastels—don't reach for the brown first. Start with a dark blue or purple base in the shadows. It sounds crazy, but it works. Laying down a layer of indigo under a layer of burnt umber gives the feathers that "oily" look that real turkeys have.

Common Mistakes in Turkey Illustrations

People always forget the spurs. Male turkeys have these nasty, sharp growths on the back of their legs. If you leave them off, your Tom looks like a hen. The legs themselves aren't smooth, either. They are scaled. Drawing every single scale will drive you insane, so just imply them with some cross-hatching near the "knees" (which are actually the ankles, but that's a whole different biology lesson).

Another big mistake is the eye. A turkey's eye is dark, almost black, and sits high on the head. It doesn't have a visible white sclera like a human eye. If you put a big white part in the eye, the bird looks like a cartoon character from a cereal box. Keep it dark, with one tiny, sharp white "glint" to show the moisture of the eye.

The beard is not hair

It looks like a beard. We call it a beard. But it's actually a tuft of specialized feathers called filoplumes. In your hand drawing of turkey, don't draw it like a goatee. It should look stiff. It grows from the chest and can drag on the ground in older birds. It doesn't have a follicle like mammalian hair; it's more like a bundle of stiff wires.

Step-by-Step Construction (The Pro Way)

Forget the hand-tracing. Try this instead for your next hand drawing of turkey:

✨ Don't miss: Why Every Mom and Daughter Photo You Take Actually Matters

- The Egg and the Ball: Draw a large, tilted egg for the body. Draw a small circle for the head, connected by a long, "S" curved line for the neck. Turkeys have incredibly flexible necks.

- The Boxy Legs: Turkeys have thick thighs (literally). Draw the upper leg as a thick mass and the lower leg as a sturdy, straight line ending in three main toes forward and one smaller toe in the back.

- Mapping the Fan: Lightly draw a giant semi-circle behind the egg. Don't draw individual feathers yet. Just get the shape of the fan right.

- Layering the Feathers: Start from the bottom and work up. Feathers on the body are like shingles on a roof. Each one overlaps the one below it. In a hand drawing of turkey, this is where you spend 80% of your time.

- The Head Details: This is where you add the snood, the caruncles, and the beak. Remember, the head is mostly featherless, so the skin texture needs to look different from the rest of the body.

Why Context Matters

Where is your turkey? Is it in a forest? A field? On a platter? (Hopefully not, if you're going for a nature study). Adding a few oak leaves or some tall grass around the feet of your hand drawing of turkey helps ground the bird. Without a background, it looks like it's floating in space. Even a simple shadow on the ground makes a world of difference.

Taking Your Drawing Further

Once you've mastered the basic hand drawing of turkey, try drawing them in different poses. A "strutting" turkey is the classic image, but a turkey "gobbling" with its neck extended is a much more dynamic, albeit uglier, subject.

Don't be afraid to mess up. Feathers are forgiving. If you get a line wrong, you can usually turn it into another feather. Just keep your pencil sharp. Dull pencils lead to "muddy" drawings, and there's nothing worse than a muddy turkey.

To really elevate your work, spend some time watching videos of wild turkeys. Look at how they tuck their wings. Notice how the "beard" swings when they move. That movement is what you're trying to capture in a static image. A great hand drawing of turkey feels like it could step off the page at any second.

Actionable Insights for Your Next Piece

- Study the anatomy first: Look at skeletal diagrams of the Phasianidae family. Knowing where the bones are helps you place the muscles and feathers correctly.

- Focus on the "V": The feathers on the breast often form a "V" shape toward the center of the chest. Following this pattern creates a sense of three-dimensional depth.

- Vary your pressure: Use a heavy hand for the dark bands on the tail feathers and a light touch for the wispy feathers near the neck.

- Limit your highlights: Only the very tops of the feathers and the wet part of the eye should be pure white. Overusing highlights makes the bird look metallic.

- Reference photos are non-negotiable: Even the best artists use references. Find a high-resolution photo of a wild turkey in natural light to see the true color transitions.

Stop tracing your hand and start looking at the bird. The complexity of a turkey's form is a masterclass in texture and value. Once you get the hang of it, you'll realize that the "hand turkey" was just a very basic introduction to one of the most interesting subjects in North American wildlife art.

Grab a 2B pencil and a sheet of toned paper. Start with the "egg" of the body. Don't worry about the feathers until the proportions are perfect. If the body is wrong, no amount of beautiful feather detail will save the drawing. Practice the "C" shapes for the neck skin. Soon, your hand drawing of turkey will look less like a classroom craft and more like a piece of professional natural history illustration.