Drawing people is hard. Honestly, it’s probably the most frustrating thing you’ll ever try to do with a pencil. You start with a vision of a graceful, flowing figure, but twenty minutes later, you’re staring at something that looks more like a wooden mannequin or, worse, a stack of poorly stacked sausages. When it comes to a drawing of a woman, the margin for error feels incredibly thin. Because female anatomy is often associated with softer transitions and specific skeletal proportions, a single misplaced line can make the whole image feel "off" in a way that’s tough to pin down.

It's not just about "talent." That’s a myth. It’s about seeing. Most people don't actually look at what’s in front of them; they draw what they think a woman looks like. They draw an idea of a face or a symbol of a hip. To get it right, you have to throw those symbols away.

The Bone Structure Nobody Talks About

If you don't understand the skeleton, your drawing will always look like it’s collapsing. It’s basically physics. The female pelvis is broader and shorter than the male pelvis, which is the literal foundation for that classic "hourglass" shape everyone talks about. But here’s the kicker: it’s not just about the width. It’s about the tilt.

The anterior pelvic tilt is often more pronounced in women. This affects how the spine curves and how the weight sits on the legs. If you draw the torso as a straight box, you’ve already lost the gesture. Think of the ribcage and the pelvis as two distinct masses connected by a flexible core. In a drawing of a woman, these two masses are rarely aligned perfectly vertically. One tilts back, the other twists forward. That's where the life is.

I remember reading an interview with the legendary Disney animator Glen Keane. He talked about "searching" for the line. He wasn't just outlining a shape; he was feeling the weight of the character. When you're sketching, you should be doing the same. Is she leaning on one leg? That’s called contrapposto. It’s a fancy Italian word for "counterpose," and it’s the secret sauce of figurative art. When one hip goes up, the shoulder on that same side usually goes down to maintain balance.

Softness is an Illusion of Light

One of the biggest mistakes is trying to draw "softness" by making everything blurry. That’s a trap. Real softness in a drawing comes from how you handle the edges of your shadows, not by avoiding hard lines altogether.

📖 Related: Kiko Japanese Restaurant Plantation: Why This Local Spot Still Wins the Sushi Game

Female musculature is often less visually "sharp" than male musculature because of a slightly higher percentage of subcutaneous fat. This layer of fat sits between the muscle and the skin, smoothing out the transitions. If you're working on a drawing of a woman, you have to be obsessed with "lost and found" edges. A lost edge is where the shadow of the figure matches the value of the background, making the border disappear. It creates a sense of atmosphere.

The Problem with "The Pretty Face"

Faces are a nightmare. Let’s be real. We are biologically hardwired to spot the tiniest mistakes in a human face. It’s a survival mechanism. If an eye is two millimeters too low, our brains scream that something is wrong.

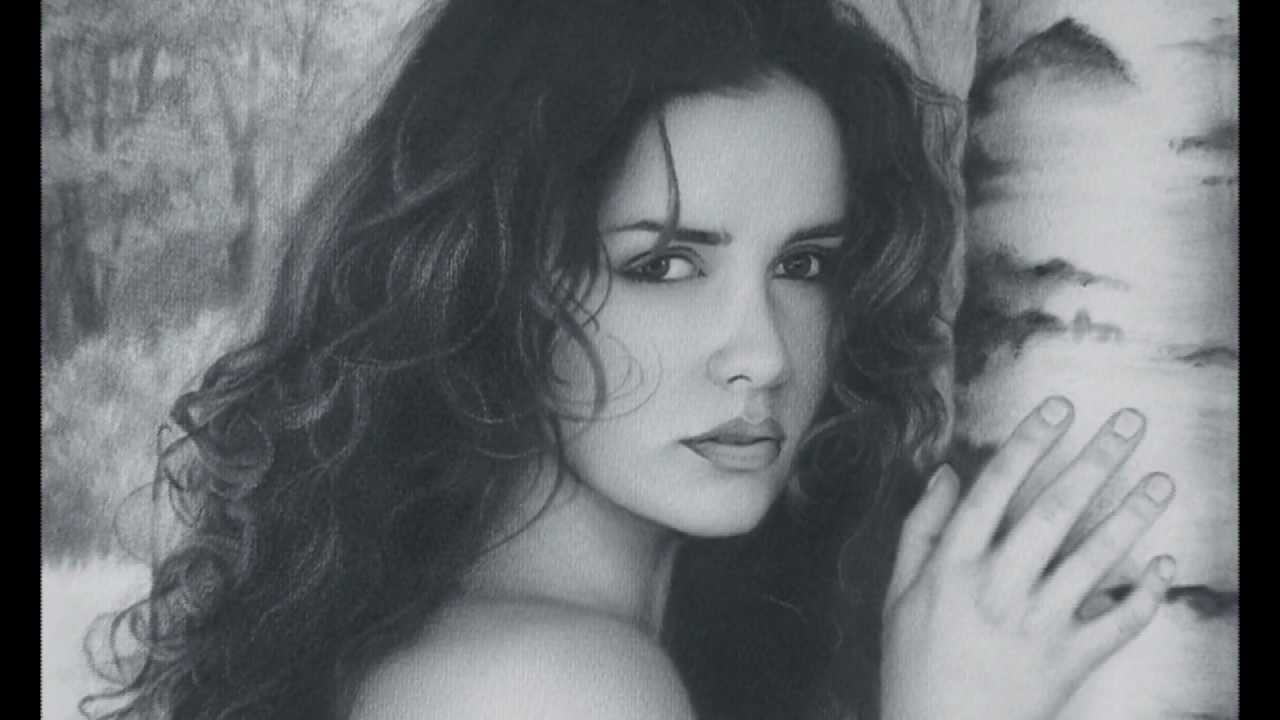

Beginners usually make the eyes too big and the forehead too small. They also tend to draw individual eyelashes like tiny spider legs. Stop doing that. Eyelashes should be treated as a dark mass, maybe with one or two stray hairs defined at the very end. The "look" of a woman’s face in a drawing is often defined by the orbital bone and the bridge of the nose, not just the features themselves.

Andrew Loomis, the dean of mid-century technical drawing, had a specific method for this. He broke the head down into a sphere and a plane. It sounds technical because it is. But once you realize the ear usually aligns with the brow line and the bottom of the nose, the "magic" of drawing starts to feel like a repeatable process rather than a lucky accident.

Fabric, Drapery, and the Body Beneath

You aren't just drawing skin. Most of the time, you're drawing clothes. But the clothes have to feel like they are being pushed out by the body underneath.

👉 See also: Green Emerald Day Massage: Why Your Body Actually Needs This Specific Therapy

There’s a concept called "points of tension." If a woman is wearing a silk dress, the fabric doesn't just hang. It pulls from the high points—the shoulders, the bust, the hips. Everything else is just "gravity." If you don't establish those tension points first, the clothing will look like it’s floating in space.

Real-world example: Look at the way John Singer Sargent painted fabric. He didn't paint every wrinkle. He painted the direction of the fold. He used bold, confident strokes to show where the fabric was stretched tight against the form and where it fell into deep shadow. In your drawing of a woman, use your darkest values in the deep folds of the clothing to give the figure weight.

Why Your Perspective is Probably Wrong

Foreshortening is the boss fight of art.

When an arm is pointing directly at the viewer, it doesn't look like an arm anymore. It looks like a series of overlapping circles. This is where most people quit. They get scared and try to "cheat" by drawing the arm slightly to the side so it’s easier to see. Don't do that.

The trick is to use "wrapping lines." Imagine the arm is a cylinder and you're drawing rubber bands around it. Those curved lines tell the viewer’s brain which way the limb is pointing. It’s a 3D trick on a 2D surface.

✨ Don't miss: The Recipe Marble Pound Cake Secrets Professional Bakers Don't Usually Share

The Mental Game of the Long Sketch

Sometimes a drawing takes ten hours. Sometimes it takes ten seconds. Both are valuable.

- Gesture drawings: These are quick, 30-second scribbles. The goal isn't "pretty." The goal is "movement." If you can't capture the essence of a woman’s pose in 30 seconds, you won't be able to do it in 30 hours.

- Long-form studies: This is where you sit down with a coffee and really dig into the values. You look at the way light hits the collarbone. You notice that the shadow under the chin isn't just black—it has reflected light from the chest.

Most people fail because they try to do a long-form study without the foundation of a gesture drawing. They build a house on sand.

Practical Steps to Improve Your Work Right Now

If you want to actually get better at a drawing of a woman, you need a system. Watching a "how to draw" video once won't do anything. Muscle memory is built through repetition and specific, focused practice.

- Start with "The Bean." This is a classic animation technique. Represent the torso and pelvis as two rounded shapes (like a kidney bean). This forces you to focus on the "squash and stretch" of the torso before you get bogged down in details like fingers or hair.

- Master the "Three-Quarter" view. Drawing a face straight-on is boring and surprisingly difficult to get symmetrical. Drawing a profile is "flat." The three-quarter view is where the depth lives. Practice the way the far eye appears slightly smaller and closer to the bridge of the nose.

- Use a limited value scale. Don't use every pencil in your kit. Use a 2B and maybe a 6B. Force yourself to create "depth" using only four shades: the white of the paper, a light grey, a mid-tone, and a dark shadow. This stops you from over-rendering and making the skin look "dirty."

- Draw from life whenever possible. Photos lie. Cameras flatten depth and distort edges. If you can't get to a life-drawing class, use a mirror. Draw your own hands. Draw your own reflection. The way light wraps around a real, 3D object is infinitely more complex than a 2D JPEG on a screen.

- Ignore the hair until the very end. Hair is a shape, not a million strings. Draw the big "clumps" of hair first. Think of it like a helmet or a hood. Only at the very last second should you add a few "flyaway" hairs to give it texture.

The reality is that a drawing of a woman is a lifelong study. Even masters like Degas or Da Vinci spent decades trying to perfect the curve of a neck or the weight of a hand. Don't be precious about your sketches. Fill a sketchbook with "bad" drawings. Eventually, the lines will start to go where you want them to. It just takes a lot of lead and even more patience.

Focus on the big shapes first. The details can wait.

Next Steps for Your Practice:

To move beyond basic sketches, pick one specific anatomical area—like the hands or the transition from the neck to the shoulders—and fill five pages of your sketchbook with nothing but that. Use a timer to limit yourself to two minutes per sketch; this prevents overthinking and forces you to prioritize the "gesture" over the "detail." Once you've completed these high-speed reps, try one slow, thirty-minute study of the same subject to apply the structural patterns you've just internalized.