Drawing people is hard. Really hard. You’ve probably spent hours staring at a blank sheet of paper or a tablet screen, trying to figure out why the arm you just sketched looks more like a pool noodle than a human limb. It’s frustrating. We see bodies every single day, yet the second we try to put pencil to paper, our brains seem to forget how joints actually work.

The truth is, the draw of human body mechanics isn't just about memorizing every single muscle in the Latin medical dictionary. Honestly, if you try to memorize all 600+ muscles before you even understand how a torso bends, you’re going to burn out before you finish your first sketchbook. Art isn't a biology exam. It’s about rhythm.

The Mental Block Behind Every Bad Sketch

Most beginners fail because they draw what they think they see, not what’s actually there. Your brain is lazy. It uses symbols. When you think "eye," your brain hands you a football shape with a circle in the middle. When you think "leg," it gives you two straight lines. To actually get good at the draw of human body, you have to kill those symbols.

Look at a professional’s gesture drawing. It’s messy. It’s fast. Sometimes it’s just five or six lines, but those lines have more "life" than a hyper-realistic rendering that took forty hours. Why? Because they captured the action rather than the anatomy. Proko, a massive name in the art education world, always hammers home the idea of "gesture" first. If the gesture is stiff, the finished painting will be stiff. No amount of perfectly shaded biceps can save a pose that looks like a mannequin falling over.

Proportions: The 7.5 Head Rule is a Lie (Sorta)

You’ve likely heard that a human is "seven and a half heads tall." While that’s a decent baseline for a generic superhero or a fashion illustration, real people are messy. Go to a coffee shop and look around. Some people have long torsos and short legs. Some people have massive hands.

💡 You might also like: The Recipe Marble Pound Cake Secrets Professional Bakers Don't Usually Share

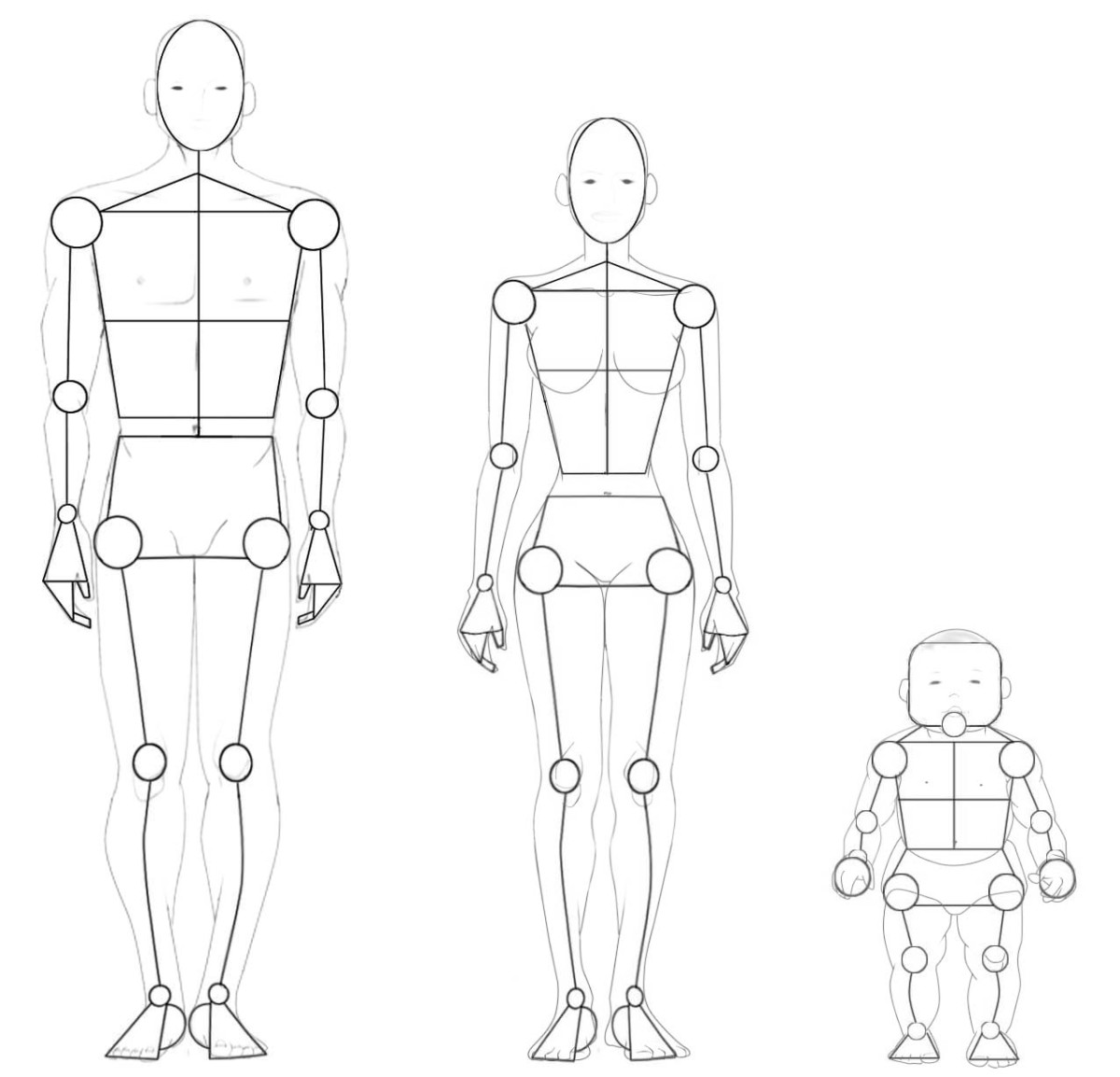

If you want to master the draw of human body figures, stop obsessing over perfect ratios. Use them as a guide, sure, but realize that the "ideal" proportion is a Renaissance invention. Andrew Loomis, the guy whose books basically taught every professional illustrator in the mid-20th century, emphasized the "manikin frame." It’s a simplified version of the skeleton. Once you can draw that frame in 3D space, you can hang the muscles on it later.

Think of the body in three main masses:

- The skull (a sphere with a jaw attached).

- The ribcage (an egg-like shape).

- The pelvis (a bowl).

The magic happens in the gaps between them. The neck and the waist are where the movement lives. If you draw the ribcage and the pelvis as one solid block, your character will look like they’re wearing a concrete suit. They can't twist. They can't breathe.

Why Foreshortening Ruins Your Weekend

Foreshortening is the final boss of figure drawing. It’s that weird perspective trick where an arm pointing at the viewer looks like a tiny stump. It feels wrong to draw it that way. Your brain screams, "An arm is long! Make it longer!" and then you end up with a drawing that looks like a funhouse mirror.

📖 Related: Why the Man Black Hair Blue Eyes Combo is So Rare (and the Genetics Behind It)

To get past this, you have to use the "coil" method. Instead of drawing the outlines of the arm, draw a series of overlapping circles or cylinders. It helps you visualize the volume. Kim Jung Gi, the late master of perspective, could do this effortlessly because he understood the 3D space the body occupied. He didn't see lines; he saw boxes and cylinders floating in a room.

The Secret is in the Landmarks

Don't try to draw skin. Draw the bones that push against the skin. These are called "landmarks." They don't move, no matter how much muscle or fat a person has.

Check these out next time you’re practicing:

- The clavicles (collarbones).

- The pit of the neck.

- The spine of the scapula (the shoulder blade ridge).

- The iliac crest (the top of the hip bone).

- The patella (kneecap).

If you get these landmarks in the right spot, the viewer’s brain will automatically fill in the rest. It’s like a connect-the-dots puzzle where the dots are bones. You can be incredibly messy with your shading as long as those structural points are accurate.

👉 See also: Chuck E. Cheese in Boca Raton: Why This Location Still Wins Over Parents

Actionable Steps to Improve Your Figure Drawing

If you’re serious about getting better at the draw of human body forms, stop drawing from your head for a while. Your imagination is currently a liar. It doesn't have enough data yet.

- Do 30-Second Gestures: Go to a site like Line-of-Action or Quickposes. Set the timer to 30 seconds. Force yourself to capture the entire pose in 10 lines or less. Do this for 20 minutes every single day. It’ll be ugly at first. Embrace the ugly.

- Study the "Bean": This is a classic technique where you represent the torso and pelvis as two rounded shapes (like beans) that squash and stretch. It’s the easiest way to understand how the core of the body moves.

- Draw the Negative Space: Don't look at the leg. Look at the shape of the empty air between the legs. Sometimes our brains are better at seeing "nothing" than "something."

- Trace the Skeleton: Take a photo of a person from a magazine or Pinterest. Lower the opacity. On a new layer (or with a marker), draw the simplified skeleton over them. Where is the spine? Where are the hips tilting?

- Vary Your Line Weight: Thick lines for heavy areas (like the bottom of a thigh) and thin lines for light areas (like the top of a shoulder). This instantly adds "weight" to your drawing.

Getting good at this isn't a linear path. You’ll have days where you feel like Da Vinci and days where you can't draw a stick figure. That’s normal. The goal isn't perfection; it's observation. Keep your eyes open, carry a sketchbook, and stop being afraid of drawing bad feet—everyone hates drawing feet, just do it anyway.

Focus on the rhythm of the spine. Look for the "S" curves in the pose. Once you find the flow, the anatomy starts to take care of itself. Forget the "correct" way to do it and focus on making the figure feel like it’s actually standing on the ground, affected by gravity. That’s when the art truly starts to happen.