You know that feeling when you're watching a modern action flick and the "master" becomes a lethal weapon after a thirty-second training montage? It’s annoying. It feels unearned. That's exactly why the master kung fu movie genre reached its absolute peak in 1978 with The 36th Chamber of Shaolin.

It didn't just show a guy punching things. It showed the grind.

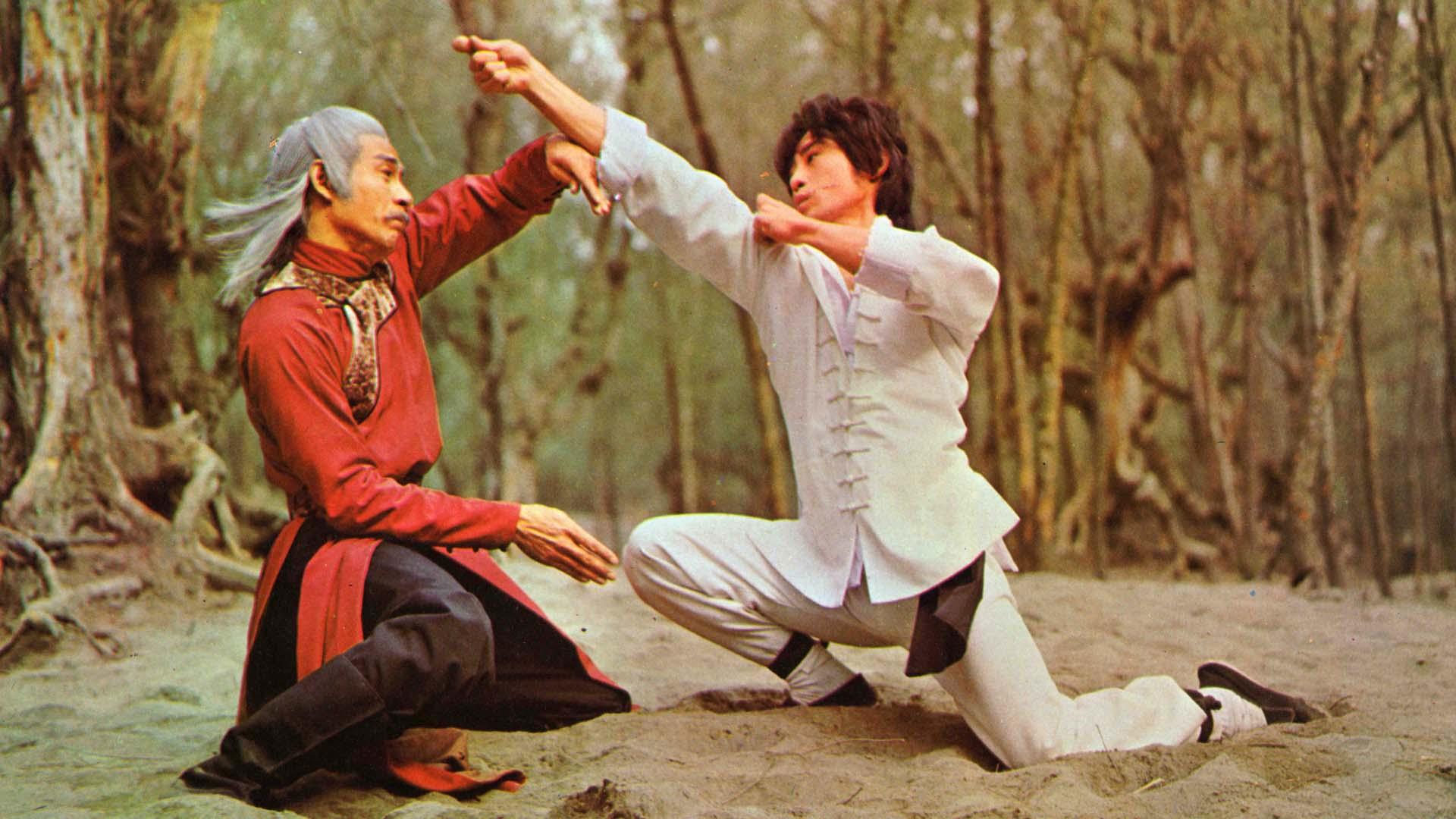

If you ask any real martial arts cinema nerd about the quintessential experience, they aren't going to point you toward the high-flying CGI of the early 2000s. They’ll take you back to the Shaw Brothers era. Specifically, they’ll point to Gordon Liu. He didn't just play a character; he embodied the archetype of the student-turned-master in a way that literally changed how movies were made in Hong Kong and, eventually, how Hollywood approached fight choreography.

The Brutal Reality of the 36 Chambers

Most people think "kung fu" just means fighting. It doesn't. The term actually refers to any skill acquired through hard work and practice over time. Director Lau Kar-leung understood this better than anyone else in the industry. Because he was a legitimate martial artist himself—descended from the lineage of Wong Fei-hung—he wanted the master kung fu movie to be an educational tool as much as entertainment.

The film follows San Te. He’s a young student who flees a Manchu massacre and seeks refuge at the Shaolin Temple. He wants revenge. The monks want peace.

What follows is the most iconic training sequence in cinema history. San Te has to progress through 35 chambers. Each one tests a specific physical or mental attribute. There’s no skipping ahead. If your balance sucks, you stay in the balance chamber. If your wrists are weak, you stay in the wrist-strengthening chamber.

It's tedious. It's grueling. Honestly, it’s kind of relatable if you’ve ever tried to learn a difficult skill.

Why the "Eye Chamber" Matters

One of the most famous segments involves San Te having to follow a flickering light with his eyes without moving his head. It sounds simple. It looks agonizing. This wasn't just "movie magic" fluff; it was based on actual traditional training methods used to develop peripheral vision and focus.

The brilliance of this specific master kung fu movie is that it treats the body as a machine that must be calibrated part by part. You see the callouses. You see the sweat. By the time San Te creates the "36th Chamber" to teach kung fu to the laity, you feel like you’ve earned that victory alongside him.

👉 See also: The Real Story Behind I Can Do Bad All by Myself: From Stage to Screen

Breaking Down the Shaw Brothers Aesthetic

The Shaw Brothers Studio wasn't just a production house; it was a factory. But it was a factory of geniuses. They used "Movable Sets" and vivid, almost garish lighting that gave these films a stage-play quality.

Some critics back in the day dismissed this as "cheap." They were wrong.

The color palettes—deep reds, vibrant yellows—were intentional. They highlighted the movement of the silk costumes. When San Te moves, the fabric moves with him, accentuating the lines of his technique. If you watch a modern film like The Matrix, you can see the DNA of the Shaw Brothers' framing. Every shot is composed to show the full body. No "shaky cam" to hide bad footwork.

Lau Kar-leung insisted on long takes. He wanted you to see that Gordon Liu was actually performing these complex sequences. It’s a level of transparency that's mostly lost in the era of rapid-fire editing and stunt doubles.

The Cultural Impact: From Shaolin to Staten Island

You can't talk about the legacy of this master kung fu movie without talking about the Wu-Tang Clan. In the early 90s, RZA and the rest of the group took the mythology of the 36th Chamber and transposed it onto the streets of New York.

"It's the 36th Chamber of death!"

The grit, the discipline, and the idea of the "outcast" training in secret to reclaim their honor resonated deeply with hip-hop culture. It gave the film a second life in the West that went far beyond the "Grindhouse" theaters of the 70s. It turned a niche Hong Kong action movie into a global philosophical touchstone.

What Most Modern Movies Get Wrong About Mastery

We live in an age of "The Chosen One" tropes.

✨ Don't miss: Love Island UK Who Is Still Together: The Reality of Romance After the Villa

Neo is "The One." Rey is naturally gifted with the Force. Even in many modern martial arts films, the protagonist is usually a "natural." The 36th Chamber of Shaolin rejects that entirely. San Te is not special. He’s just stubborn.

That is the core of a true master kung fu movie. It’s the philosophy that greatness is accessible to anyone willing to suffer for it. When we watch San Te struggle to jump across floating logs in the water chamber, we’re seeing a human being fail.

We see him fail a lot.

Then he succeeds.

That shift—from incompetence to mastery—is the ultimate cinematic payoff. Modern directors often rush this because they think the audience is bored by the "middle part." But the middle part is the movie. Without the struggle, the final fight is just two people hitting each other. With the struggle, it's a climax of character development.

Essential Master Kung Fu Movies You Need to See

If you're looking to dive deeper into this world, don't just stop at one film. The genre is vast, but a few titles stand out for their commitment to the "mastery" narrative:

The Eight Diagram Pole Fighter (1984): Also starring Gordon Liu. It’s darker, bloodier, and deals with the psychological toll of violence. The training here involves de-toothing wolves (wooden ones, don't worry) to simulate disarming opponents.

Drunken Master (1978): This is the flip side of the coin. Jackie Chan turned the master-student dynamic into a comedy. It’s less about the sanctity of the temple and more about the unorthodox, grueling methods of a beggar master.

🔗 Read more: Gwendoline Butler Dead in a Row: Why This 1957 Mystery Still Packs a Punch

Five Deadly Venoms (1978): This is basically a "whodunit" mystery wrapped in a kung fu flick. Each student has a specific animal style (Centipede, Snake, Scorpion, Lizard, Toad). It focuses on how different styles counter one another.

Ip Man (2008): A modern masterpiece. While it uses more contemporary filmmaking techniques, it honors the tradition of the Wing Chun style and the dignity of the master.

How to Appreciate the Technical Craft

Next time you put on a master kung fu movie, try to ignore the (often hilariously bad) English dubbing. Switch to the original audio with subtitles. Listen to the rhythm of the breath.

Watch the "shape" of the fights. In 36th Chamber, notice how the weapons change. San Te eventually develops the three-section staff. Why? Because he realizes a straight staff has limitations against a sword. That kind of tactical evolution is what separates a "master" film from a standard "action" film.

The choreography isn't just a dance; it's a conversation. One person asks a question (an attack), and the other provides an answer (a block or counter).

Actionable Steps for the Aspiring Cinephile

If you want to truly understand why this genre holds such a grip on film history, you have to do more than just watch. You have to contextualize.

- Start with the Shaw Brothers Library: Most are available on streaming services like Arrow Video or even YouTube. Search for "Celestial Pictures" versions; they are the remastered high-definition prints.

- Look for the Director: Seek out films by Lau Kar-leung or Yuen Woo-ping. Their styles are distinct. Lau focuses on "authentic" southern styles, while Yuen (who did Crouching Tiger and The Matrix) is more about the "spectacle" and flow.

- Pay Attention to the Geometry: Notice how masters use the environment. A table isn't just a table; it's a shield or a platform.

- Read the History: Pick up a copy of Iron Fists: Branding the 20th-Century Martial Arts Movies by Stephen Teo. It explains the political and social pressures that shaped these films.

The master kung fu movie isn't just a relic of the 1970s. It’s a blueprint for storytelling that values process over results. In a world of instant gratification, watching a man spend five years learning how to punch through a bowl of water is strangely cathartic. It reminds us that anything worth doing is going to take a really, really long time.