You probably heard it as a kid. Maybe your grandma recited that creepy opening line about a parlor and a winding stair. The Spider and the Fly is one of those rare poems that manages to be both a charming nursery rhyme and a deeply unsettling psychological profile of a predator. Written by Mary Howitt in 1829, it hasn’t aged a day because, honestly, the way people manipulate each other hasn't changed much in two centuries.

It's about a spider. It's about a fly. But it's really about how easily we let our guards down when someone tells us exactly what we want to hear.

Most people think it’s just a simple story for children. It’s not. When you actually look at the mechanics of the poem, Howitt was doing something much more sophisticated than just telling kids to avoid strangers. She was mapping out the exact stages of grooming and manipulation. It’s basically a masterclass in how flattery bypasses logic.

What Actually Happens in The Spider and the Fly?

The setup is classic. We have the Spider, who is the ultimate "smooth talker." He invites the Fly into his home—his "parlor." He uses a series of different tactics, and what's interesting is how the Fly reacts to each one.

At first, the Fly is smart. She’s skeptical. When the Spider offers her a place to rest on his "silken sheets," she shuts him down immediately. She knows that whoever goes up that winding stair never comes back down. This is the version of ourselves we like to think we are—logical, cautious, and aware of the red flags.

But the Spider doesn’t give up. He’s persistent. He tries the "generosity" angle next, offering her sweets from his pantry. Again, she says no. She’s heard the rumors. She knows his pantry is just a graveyard.

Then, the Spider pivots. He stops talking about what he has and starts talking about what she has. He talks about her "pearl and silver wing" and her "brilliant eyes." And that is where the defenses crumble. It’s a terrifyingly accurate depiction of how vanity works. The Fly stays to hear more, and before she knows it, she’s caught. The poem ends with the Spider dragging her up to his "dismal den," and she’s never heard from again.

💡 You might also like: Greatest Rock and Roll Singers of All Time: Why the Legends Still Own the Mic

Why the "Flattery" Pivot Matters

Why did the third attempt work when the first two failed? It’s a psychological trick. When the Spider offered physical things (a bed, food), the Fly could evaluate them logically. She didn't need a bed. She wasn't hungry. But when he attacked her ego, he moved the conversation from the physical world to the emotional one.

Howitt was tapping into a very real human vulnerability. We are often our own worst enemies because we want to believe the nice things people say about us, even when we know the person saying them is dangerous.

Mary Howitt: The Woman Behind the Web

Mary Howitt wasn't just some random lady writing rhymes. She was a powerhouse in the 19th-century literary world. Along with her husband, William, she wrote over 180 books. She was a radical for her time, a Quaker who eventually converted to Catholicism, and she spent a huge chunk of her life translating Hans Christian Andersen into English.

If you’ve ever read The Ugly Duckling or The Thumbelina in English, you likely have Mary Howitt to thank for the early versions.

She understood the "cautionary tale" better than almost anyone. In the Victorian era, children’s literature was often brutally direct. There was no "softening the blow." If the Fly is foolish enough to listen to a predator, the Fly gets eaten. Period. There is no last-minute rescue by a woodcutter.

Howitt wrote The Spider and the Fly specifically to warn her own children about the "idle, flattering words" of people who don't have their best interests at heart. She lived in a time of massive social upheaval, where the city was becoming a more dangerous, anonymous place. Her poem was a survival guide for the soul.

📖 Related: Ted Nugent State of Shock: Why This 1979 Album Divides Fans Today

Modern Pop Culture and the Spider’s Legacy

The reason this poem still ranks so high in our cultural consciousness is that it has been referenced by everyone from Radiohead to Lewis Carroll.

- Lewis Carroll's Parody: In Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, Carroll wrote "The Lobster Quadrille" ("Will you walk a little faster?" said a whiting to a snail), which is a direct play on Howitt’s meter and structure.

- The Rolling Stones: They have a song called "The Spider and the Fly." It’s not a direct retelling, but it uses the same imagery of a predatory encounter in a bar.

- Film and Noir: The "Spider" archetype—the charming villain who lures the protagonist into a trap—is the foundation of the entire Femme Fatale or Homme Fatale trope in cinema.

It’s kind of wild that a poem from 1829 is still the go-to metaphor for predatory behavior. Whether it’s a phishing email promising you millions or a "friend" who only calls when they need a favor, the Spider is still very much active.

Breaking Down the Language: "Cunning" and "Wily"

The vocabulary Howitt uses is specific. She describes the Spider as "wily" and "cunning." These aren't just synonyms for "smart." They imply a misuse of intelligence. The Spider is a strategist. He isn't using brute force; he’s using psychological warfare.

The Fly, on the other hand, is described with words like "silly" and "heedless." It’s a harsh judgment. Howitt isn't just blaming the predator; she’s warning the prey that their own lack of attention is what makes them vulnerable. In the final stanza, she drops the fiction entirely and speaks directly to the reader:

"And now dear little children, who may this story read,

To idle, silly flattering words, I pray you ne’er give heed..."

She moves from "Once upon a time" to "Listen to me, this is real life" in a heartbeat.

👉 See also: Mike Judge Presents: Tales from the Tour Bus Explained (Simply)

Common Misconceptions About the Poem

A lot of people think the Spider and the Fly is an Aesop Fable. It’s not. While it feels like one, Aesop lived in ancient Greece, and this poem is distinctly British and Victorian.

Another big mistake is thinking the Fly is a child. In the poem, the Fly is often depicted in illustrations as a tiny, dainty creature, but the "lesson" is universal. It applies to business deals, romantic relationships, and political rhetoric. It's not just about "stranger danger." It's about anyone who uses your own vanity to cloud your judgment.

Some critics argue the poem is too dark for kids. But honestly? Kids love the darkness. They understand the stakes. The "winding stair" is a terrifying image because it’s a one-way trip. If the Fly had escaped at the end, the poem wouldn't be famous. It’s the tragedy that makes it stick.

Actionable Takeaways: How to Spot a "Spider" Today

Reading the poem is one thing, but applying it is another. If you want to avoid the "winding stair" in your own life, you have to recognize the patterns the Spider used.

- Beware the "Exclusive" Invite: The Spider starts by making his parlor sound like an elite club. If someone is trying to isolate you or make you feel "special" by sharing a secret or an exclusive opportunity, be cautious.

- Watch for the Pivot: If someone tries to convince you of something and fails, watch what they do next. Do they walk away? Or do they start complimenting your intelligence, your looks, or your "potential"? If the tactic changes to flattery, it’s a red flag.

- Trust the Rumors: The Fly knew the rumors about the Spider’s pantry. She chose to ignore them because the Spider’s words were louder than the community’s warnings. If "everyone says" someone is bad news, they're probably right.

- Check Your Own Ego: The Fly died because she wanted to believe she had "brilliant eyes." When we feel a sudden rush of pride from a stranger's compliment, that's the exact moment we should take a step back and ask: Why are they telling me this now?

To really internalize the lesson, read the poem aloud. Notice the rhythm. It sounds like a dance—a predatory, circular dance. The Spider circles the Fly with words until she’s too dizzy to fly away.

For further study on the Victorian cautionary tale, look into the works of Hilaire Belloc or the darker side of the Brothers Grimm. Understanding the history of these stories helps us see that the "parlors" of today—social media, marketing, and high-pressure sales—are just the same old webs with different names.

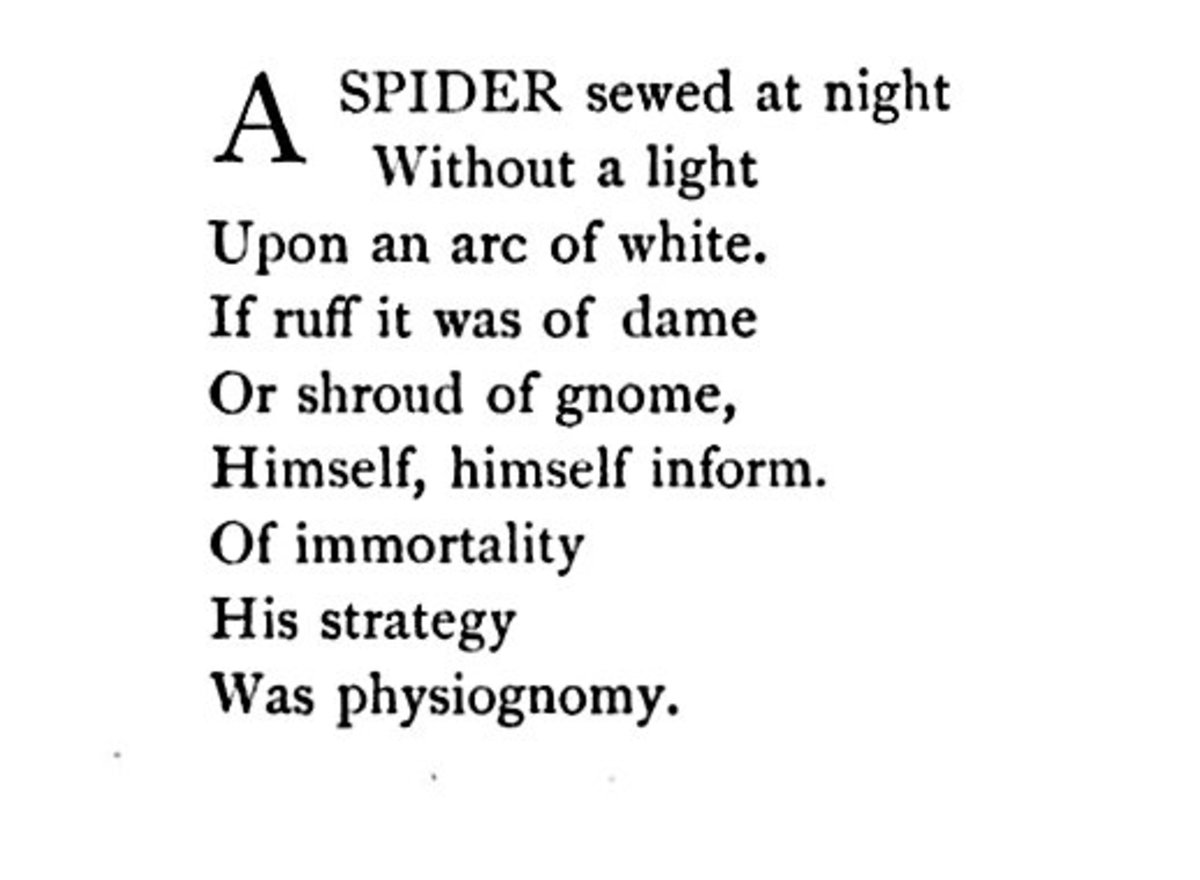

Check the original text of the poem in a library or a reputable online archive like the Poetry Foundation to see the full, unedited stanzas. Comparing different historical illustrations of the poem—from the early woodcuts to the 1920s Art Deco versions—can also show you how every generation reinterprets this specific type of danger.