When you hear the name Marty Robbins, your brain probably goes straight to a dusty street in El Paso at high noon. You think of gunfighters, white sport coats, and maybe a pink carnation. But in 1958, Marty did something that confused his label and delighted his fans: he released an album called Marty Robbins Singing the Blues. It wasn’t just a clever title. He actually did it. He took that smooth, velvet-country voice and dragged it through the mud of American blues and jazz-inflected pop.

He wasn't the first country star to flirt with the blues, but he was arguably the one who did it with the most grace. Most people forget that Marty was a vocal chameleon. One minute he’s a cowboy, the next he’s a teen idol, and then suddenly he’s a Hawaiian crooner. This specific era of his career, specifically the late 50s, was a pivot point.

Why Marty Robbins Singing the Blues Changed the Game

Most country artists in the 50s stayed in their lane. If you were a "hillbilly" singer, you sang about the hills. If you were a honky-tonk man, you sang about the bar. But Marty had this restless energy. He was listening to everything. When he sat down to record the tracks that would eventually define Marty Robbins singing the blues, he wasn't trying to mimic Muddy Waters or B.B. King. That wouldn't have worked. It would have sounded like a caricature.

Instead, he channeled the "city blues"—that polished, slightly mournful sound that bridged the gap between Nashville and Tin Pan Alley. It’s why the album feels so timeless. It doesn't sound like a 1958 museum piece. It sounds like a guy sitting in a dimly lit room at 2:00 AM, nursing a drink and wondering where it all went wrong.

The Guy Could Literally Sing Anything

Seriously. It’s annoying how good he was.

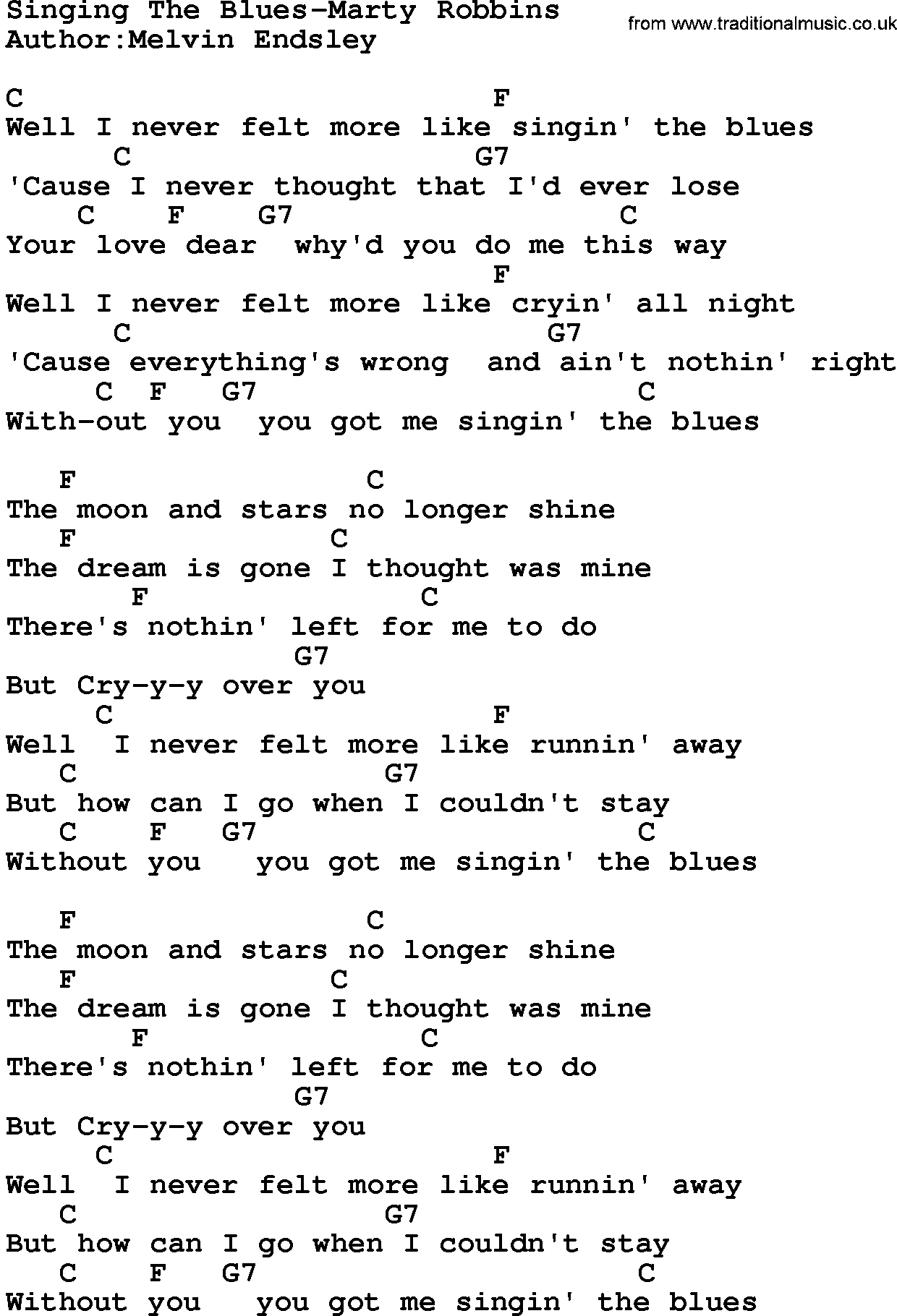

A lot of modern listeners don't realize that Marty’s biggest hit at the time was actually "Singing the Blues," written by Melvin Endsley. Now, here is where the history gets a bit tangled. Marty recorded it first in 1956. It was a massive #1 hit on the country charts. But then Guy Mitchell, a pop singer, covered it and it blew up on the pop charts. Marty didn't care; he just kept moving. He knew he had a hit on his hands, and it validated his instinct that country fans were ready for something a bit more "blue."

He had this way of sliding into notes. It's a technique called glissando, though he probably just called it "singing." He would start a bit flat and then swell into the pitch. In blues music, that's everything. It’s the tension and the release.

The Songs That Defined the Vibe

If you listen to the track "Mean Mama Blues," you hear a version of Marty that’s stripped down. It’s not the lush, orchestral arrangements of his later 60s work. It’s raw. The guitar work is stabbing and rhythmic. Honestly, it's closer to rockabilly than traditional blues, which makes sense given that Elvis was currently changing the world just a few hundred miles away.

Then you have "Be My Love Tonight." It’s got that shuffle. That swing. You can almost feel the sawdust on the floor.

What people get wrong about this era:

They think he was just chasing a trend. They see the success of Elvis or Jerry Lee Lewis and assume Marty was just a copycat. That’s a mistake. Marty’s interest in the blues predated the rock and roll explosion. He grew up in the Arizona desert, listening to a wild mix of Mexican folk music, Western swing, and the blues records that made their way out West.

👉 See also: When Was Kai Cenat Born? What You Didn't Know About His Early Life

He wasn't chasing a trend; he was finally allowed to show his true range.

The Production Secrets of the 1950s

Recording in the late 50s was a whole different beast. No Auto-Tune. No infinite tracks. You had a room, a few mics, and a band that had to play it right the first time. Marty worked frequently with the "A-Team" of Nashville session musicians. We're talking about guys like Grady Martin on guitar and Bob Moore on bass.

When you listen to Marty Robbins singing the blues, you’re hearing the literal sound of a room. The natural reverb. The way the drums bleed into the vocal mic. It creates this intimacy that you just can't replicate in a digital DAW today.

Grady Martin’s guitar work on these tracks is particularly insane. He was using a Bigsby vibrato tailpiece to get those wobbling, mournful notes. It mimicked Marty’s vocal trills perfectly. It was a duet between a man and a piece of wood and wire.

Why the "Western" Guy Went "Blue"

It seems like a contradiction. How does the "El Paso" guy fit into the blues?

The truth is that Western music and the blues are cousins. They both deal with isolation. They both deal with the consequences of bad decisions. A cowboy dying in the desert isn't that different from a man losing his soul in a delta city. Marty understood that the emotional core was identical.

- Isolation: The lone rider vs. the lonely singer.

- Regret: The "I shouldn't have shot that guy" vs. "I shouldn't have let her go."

- Fate: Both genres have this heavy sense that the end is coming and there’s nothing you can do about it.

By the time he released Marty Robbins Singing the Blues, he had already established himself as a storyteller. This album just changed the setting of the story. Instead of a campfire, it was a streetlamp.

The Commercial Risk

Make no mistake: his label, Columbia Records, was nervous. They had a gold mine with his Western ballads. Why mess with the formula?

But Marty was a rebel. He famously loved NASCAR racing—he actually competed in the Winston Cup Series. A guy who drives a car at 150 mph isn't going to be scared of a jazz chord. He pushed for the bluesy sound because he was bored. He wanted to prove he was a singer, not just a country singer.

✨ Don't miss: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

He won. The fans followed him.

The Legacy of the "Blue" Sound in Modern Music

You can hear the echoes of Marty Robbins singing the blues in artists today. Think about Chris Stapleton. Think about Orville Peck. These guys don't care about genre lines. They mix the twang of a Telecaster with the soul of a blues shouter.

Marty paved that road.

He showed that a country artist could have "soul." Before Marty, "soul" was a term reserved for R&B. But after 1958, people realized that a white kid from Glendale, Arizona, could have just as much blue in his blood as anyone else.

It’s also worth mentioning his influence on the "Nashville Sound." Along with producers like Chet Atkins and Owen Bradley, Marty helped move country music away from its "raw" roots toward something more sophisticated. It was a double-edged sword, sure, but it saved country music from becoming a niche regional genre. It made it global.

A Note on the Lyrics

The lyrics on these records are deceptively simple.

"I've got the blues, I've got the blues..."

It’s not Shakespeare. But Marty’s delivery makes it feel like it is. He had this way of hitting a high note and letting it crack just a tiny bit. It’s a "cry in the voice." That’s something you can't teach. You either have it or you don't. Marty had it in spades.

When he sings about being "lonely and blue," he’s not just saying the words. He’s inviting you into the feeling. It’s empathetic. It’s human.

🔗 Read more: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

How to Listen to Marty Robbins Like an Expert

If you're just starting out, don't just hit shuffle on Spotify. You need to hear the progression.

- Start with "Singing the Blues" (1956): This is the foundation. It’s catchy, it’s light, but you can hear the blues influence creeping in.

- Move to the full 1958 album: Listen to it on a good pair of headphones. Pay attention to the space between the notes.

- Compare it to "El Paso": Notice the difference in his vocal texture. In "El Paso," he’s a narrator. In his blues tracks, he’s the protagonist.

- Check out the live recordings: If you can find old footage of Marty performing these songs, watch his face. He’s feeling every second of it.

The Gear That Made the Sound

For the nerds out there, Marty’s sound was a combination of his own natural pipes and the high-end ribbon microphones used at the time, likely the RCA 44-BX. These mics were famous for their "figure-8" pickup pattern and their ability to capture a warm, bottom-heavy sound. This is why his voice sounds so "thick" on these recordings. It wasn't just him; it was the physics of the 1950s.

His guitarists were often playing through small tube amps pushed to the brink of breakup. That slight distortion you hear? That’s not a pedal. That’s a vacuum tube literally running too hot. It’s glorious.

Final Thoughts on a Legend

Marty Robbins was never just one thing. He was a racer, a cowboy, a songwriter, and a bluesman.

Whenever people talk about Marty Robbins singing the blues, they are talking about a moment in time when music was less about "branding" and more about "feeling." He didn't have a social media manager telling him to stay on brand. He had a voice and a heartbeat.

He died in 1982, but his influence is everywhere. Every time a country singer lets their voice break on a sad note, or a rock band tries to add a little twang to their soul, Marty is there.

He proved that the blues aren't a geography. They aren't a race. They aren't a specific set of chords. The blues are just what happens when a human being gets honest about their pain. Marty was as honest as they come.

Actionable Next Steps

To truly appreciate this era of music history, don't just read about it—experience the nuances of the production and the performance yourself.

- Listen for the "slapback" echo: On many of his bluesy tracks, the engineers used a tape delay to create a quick echo. This is a hallmark of the 1950s sound. Try to isolate that sound in your ears; it’s what gives the vocals that "haunting" quality.

- Analyze the song structure: Notice how Marty often uses the AAB blues structure (repeating the first line twice before a rhyming third line). It’s a classic form that he adapted perfectly for a country audience.

- Explore the "Nashville A-Team": Look up the session musicians who played on these 1958 sessions. Following the careers of guys like Grady Martin or Floyd Cramer will give you a PhD-level understanding of how the "Golden Era" of Nashville was actually built.

- Check the vinyl bins: If you find an original mono pressing of Marty Robbins Singing the Blues, buy it. The mono mixes were often punchier and more intentional than the early stereo "re-channeling" that happened later.