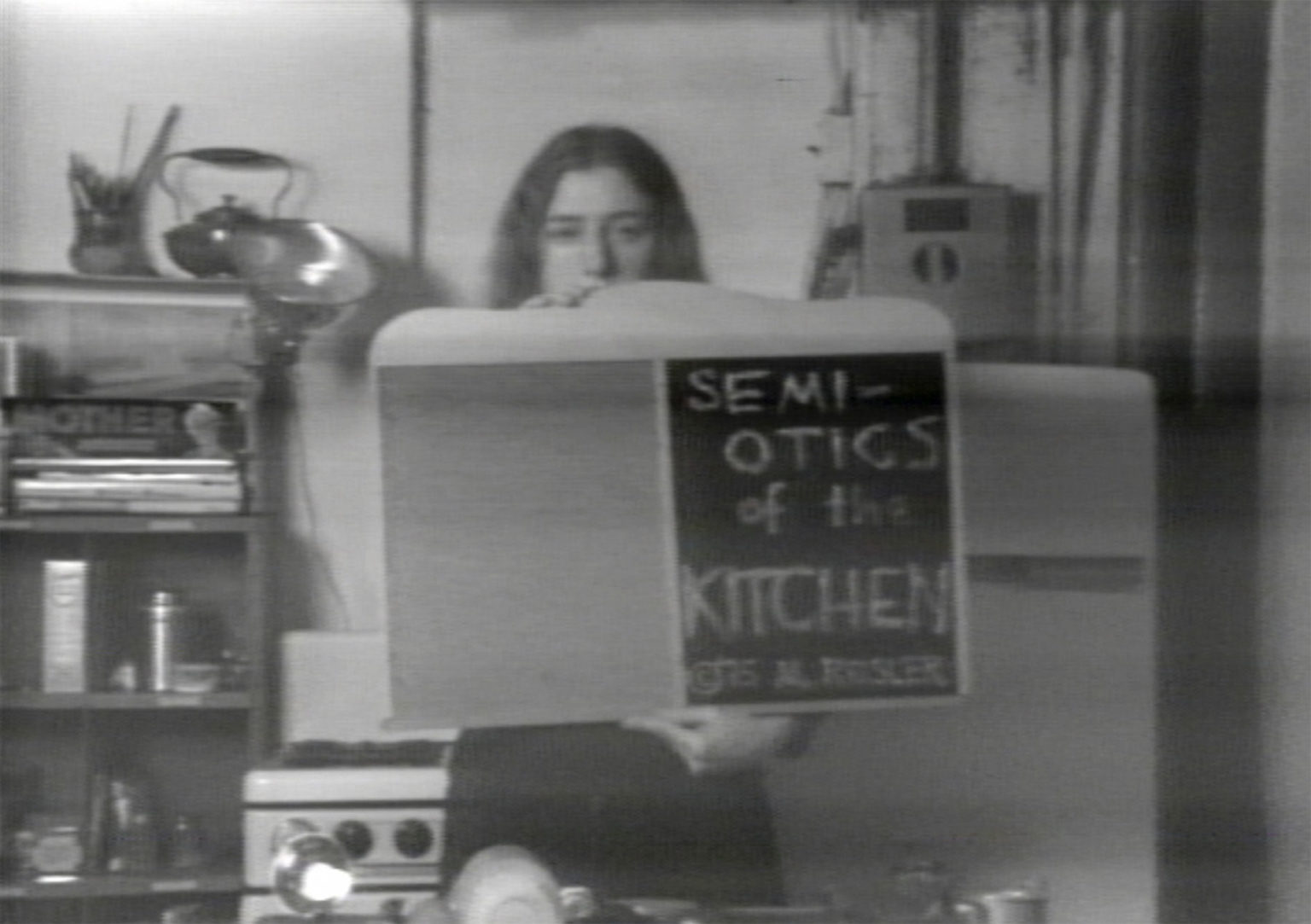

If you’ve ever watched a cooking show and felt a weird, creeping sense of dread, you’re basically channeling Martha Rosler. In 1975, she walked into a kitchen, turned on a camera, and proceeded to redefine what video art could actually do. It wasn't fancy. It wasn't high-budget. Honestly, it looks like something your aunt might have filmed in her basement if she’d suddenly snapped while making a salad. But Martha Rosler Semiotics of the Kitchen 1975 isn't just a relic of the seventies feminist movement; it’s a biting, aggressive, and deeply funny takedown of how society expects women to behave in domestic spaces.

Rosler stands behind a table. She’s got a deadpan expression that could wither a cactus. One by one, she picks up kitchen tools in alphabetical order. Apron. Bowl. Chopper. Dish. But instead of showing you how to whip up a nice soufflé, she treats these objects like weapons or strange, alien artifacts. When she gets to the letter "L" for ladle, she doesn't scoop soup; she flings it through the air with a violent flick of the wrist. It’s a performance of frustration. It's an alphabet of rage.

What the Heck is "Semiotics" Anyway?

The title sounds like a grad school thesis, and that's intentional. Rosler was playing with the idea of semiotics—the study of signs and symbols. In the 1970s, thinkers like Roland Barthes were all over the place, talking about how everything in our culture carries a hidden meaning. A kitchen isn't just a room where you boil pasta. It’s a "sign" for domesticity, motherhood, and the "woman's place."

By naming it Martha Rosler Semiotics of the Kitchen 1975, she’s telling us she’s going to dismantle those signs. She’s taking the "language" of the kitchen and speaking it with a heavy, angry accent. When she uses a nutcracker, she isn't thinking about walnuts. The way she snaps it shut feels like a threat. You’ve probably felt that way too—trapped by a role or a job where the tools you’re given feel more like shackles than helps.

She's basically saying that the kitchen is a system of signs that represents a woman’s "natural" role. By performing these tasks "wrong," she breaks the system. It’s a bit like when a computer glitch makes a character in a video game start T-posing. It reveals the underlying code. Rosler is revealing the social code of the 1970s housewife, and she’s doing it with a rolling pin and a meat tenderizer.

The Julia Child Connection You Might Have Missed

You can't talk about this piece without talking about the "The French Chef." Julia Child was the undisputed queen of the televised kitchen back then. She was breezy, competent, and made everything look like a delightful romp through butter and wine. Rosler’s performance is the "anti-Julia."

📖 Related: Finding the Right Words: Quotes About Sons That Actually Mean Something

While Child was instructional, Rosler is obstructive. Child invited you in; Rosler stares you down. The video was filmed at the University of California, San Diego, and it has this incredibly raw, black-and-white aesthetic. There are no jump cuts. No upbeat music. No "bon appétit!" at the end. Instead, Rosler ends the video by using her own body to form the letters U, V, W, X, Y, and Z. She becomes the tool. She becomes the sign.

It’s easy to forget how radical this was. In 1975, video art was barely a thing. Most people were still getting used to the idea that a TV could be used for something other than the news or sitcoms. Rosler grabbed a Portapak—the first portable video camera system—and decided to make something that felt unpolished. That "unpolished" look is exactly why it still feels modern. It’s the ancestor of the "story" or the "reel," but instead of a filter, it has a soul-crushing sense of reality.

Why the Alphabetical Order Matters

Why go A to Z? It seems a bit literal, doesn't it? Well, that's the point. The alphabet is the most basic structure of language. By fitting her "domestic revolt" into an alphabetical list, Rosler is showing how deeply ingrained these expectations are. They are the ABCs of being a woman in the mid-twentieth century.

- The Apron (A): She puts it on like armor. It’s not a garment; it’s a uniform for a war she didn’t sign up for.

- The Fork (F): She stabs the air. It’s rhythmic. It’s scary.

- The Ice Pick (I): This one is particularly intense. The way she handles it reminds you that the kitchen is full of sharp, dangerous things that we pretend are just "utensils."

There’s a specific kind of "housewife psychosis" being channeled here. Betty Friedan wrote about "the problem that has no name" in The Feminine Mystique, and Rosler gave that problem a visual language. It’s the sound of a knife hitting a wooden board too hard. It’s the silence between the clinking of spoons.

The Enduring Legacy of Martha Rosler Semiotics of the Kitchen 1975

Believe it or not, people are still parodying this. In 2003, Rosler actually did a "sequel" or a sort of live "Update" at the New Museum. Artists like Erykah Badu have referenced the aesthetic. It’s become a shorthand for "feminist critique of the domestic."

👉 See also: Williams Sonoma Deer Park IL: What Most People Get Wrong About This Kitchen Icon

But there's a deeper layer here about labor. Rosler wasn't just mad about cooking dinner. She was looking at how "women's work" is often invisible and unpaid. By bringing the tools into an art gallery context (or a video meant for one), she forces the viewer to look at the physical labor involved. The strain in her arm as she uses the egg beater isn't "charming." It’s work.

People often get wrong that this is just about "hating the kitchen." It's not. Rosler has clarified in interviews that she’s looking at the representation of the kitchen. She’s mad at the commercials, the TV shows, and the magazines that told women their only path to fulfillment was through a perfectly polished floor and a roast chicken. She’s attacking the myth, not the stove.

How to View It Like a Pro

If you watch it today, don't look for a plot. There isn't one. Look at her eyes. Rosler stays completely in character—a character she calls a "zombie." She’s a person who has been hollowed out by her environment and is now just going through the motions with a hidden, violent energy.

Pay attention to the sound. The "clack" of the metal. The "thud" of the wood. The audio is harsh. It’s meant to be uncomfortable. Most "lifestyle" content today is designed to be ASMR—soothing, soft, pleasant. Martha Rosler Semiotics of the Kitchen 1975 is the opposite of ASMR. It’s designed to wake you up, not put you to sleep.

Critics often point out that Rosler’s work bridges the gap between the "Conceptual Art" of the 60s (which was often very cold and math-heavy) and the "Identity Politics" art of the 80s and 90s. She took the cold, logical structure of the alphabet and injected it with hot, feminine rage. That’s why it’s in the MoMA. That’s why art students still have to watch it. It’s a perfect "fuck you" to the status quo, delivered with a tea towel over the shoulder.

✨ Don't miss: Finding the most affordable way to live when everything feels too expensive

Practical Insights: What We Can Learn Today

We live in an era of "TradWives" on TikTok and perfectly curated Pinterest kitchens. The pressure to perform domesticity as an aesthetic has never been higher. Rosler’s work reminds us to look under the hood.

- Question the "Natural": If something is presented as "just the way things are" (like who does the dishes or how a kitchen should look), ask who benefits from that arrangement.

- Use What You Have: You don't need a $10,000 camera to make a point. Rosler used a basic video setup and some stuff she found in a cupboard.

- Humor is a Weapon: The video is funny. It’s absurd. Using humor to point out systemic issues is often more effective than a dry lecture.

To truly understand Martha Rosler Semiotics of the Kitchen 1975, you have to see it as a performance of "frustrated speech." When she can't find the words to describe her boredom and entrapment, she uses a meat cleaver. It’s a primal scream in a linoleum-covered room.

Next time you’re scrolling through a "10 Best Kitchen Hacks" video, think of Martha. Think of the ladle being flung across the room. It’s a reminder that the spaces we inhabit—especially the ones we’re told are "safe" or "nurturing"—are often the sites of our most intense internal battles.

To see the piece in its full context, search for the original six-minute video on the Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI) website or the MoMA digital archives. Don't just watch the clips; watch the whole thing from A to Z. It’s the only way to feel the cumulative weight of the alphabet she’s building. Then, take a look at your own kitchen. Is it a workspace, or is it a set? The answer might change how you see your daily routine forever.