Imagine you’re sitting in a small, hand-carved outrigger canoe. The sun is blistering. There isn't a speck of land in any direction, just a relentless, deep blue horizon that looks the same at every compass point. To most of us, this is a death sentence. But to a Marshallese navigator from a few centuries ago, the water wasn't a void. It was a map. They didn't have magnetic compasses or sextants, and they definitely didn't have satellites. They had the Marshall Islands stick chart.

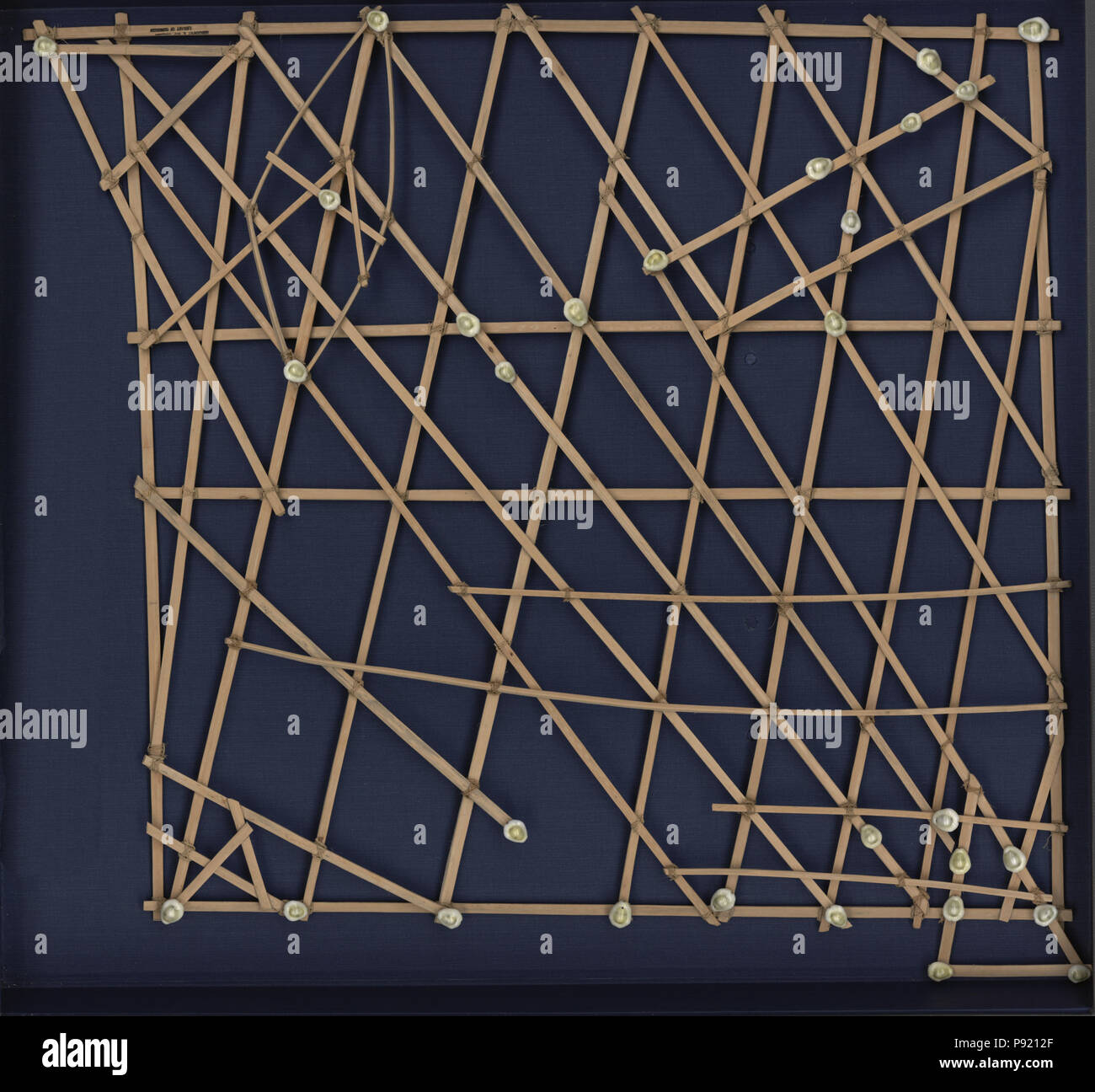

These aren't maps in the way we think of them. If you look at one in a museum today, it looks like an abstract art project—a chaotic grid of coconut midribs tied together with fiber, adorned with small white cowrie shells. But for the people of the Ratak and Ralik chains, these were sophisticated data visualization tools.

They were secrets.

What a Marshall Islands stick chart actually represents

Honestly, the biggest mistake people make is thinking these charts were taken out to sea. They weren't. Navigators didn't pull out a bundle of sticks while crashing through six-foot swells to figure out where they were. That would be like trying to read a delicate architectural blueprint during a hurricane. Instead, the Marshall Islands stick chart was a mnemonic device. It was a teaching tool used on land to memorize the "feel" of the ocean.

Once a navigator memorized the patterns, they left the sticks behind. The map was in their mind, their muscles, and even their stomach.

The three types of charts

Navigators categorized these tools based on how much "zoom" they had. It’s kinda like switching between a city map and a continental atlas.

👉 See also: Weather in Kirkwood Missouri Explained (Simply)

- The Mattang: This is the one you usually see in gift shops now. It’s a small, square-ish chart that doesn’t show specific islands. Instead, it’s a general diagram of how waves behave when they hit a generic landmass. It’s the "theory" version. It taught students how swells bend, intersect, and reflect.

- The Meddo: These were more specific. A Meddo might show a small cluster of islands—maybe five or six—and the unique wave patterns between them. It was a regional guide.

- The Rebbelib: This was the big picture. A Rebbelib covered a huge chunk of the Marshall Islands, sometimes representing an entire island chain. The shells represented the islands, and the sticks showed the major ocean swells.

It’s all about the swells

Most people look at the ocean and see waves. A Marshallese navigator saw "swell." There's a difference. Waves are local; they're caused by the wind blowing right now. Swells are much deeper pulses of energy that have traveled thousands of miles from distant storms.

The Marshall Islands stick chart recorded how these swells interacted with the low-lying coral atolls. Because the islands are so low—many are only a few feet above sea level—you can't see them from very far away. But you can "see" them through the water long before they appear on the horizon.

The science of refraction and reflection

When a massive ocean swell hits an island, a few things happen. The swell might bend around the island (refraction) or bounce off it (reflection). This creates a "interference pattern."

Think of it like throwing two stones into a still pond at the same time. Where the ripples meet, they create a unique "criss-cross" texture. Navigators called these boot. If you knew how to read the boot, you could follow the "seam" of the water straight to an island that was still forty miles away and invisible to the naked eye. They actually used to lie down in the bottom of the canoe to feel the vibration of the hull. They were literally sensing the shape of the seafloor through their bodies.

Why this knowledge almost disappeared

For a long time, this was "forbidden" knowledge. It wasn't just open to everyone. Navigation was a high-status, hereditary craft passed down from father to son or uncle to nephew. You had to prove yourself before a Master Navigator (paliuw) would even show you a Marshall Islands stick chart.

✨ Don't miss: Weather in Fairbanks Alaska: What Most People Get Wrong

Then came the late 19th century. Western ships arrived with metal compasses and printed charts.

Suddenly, the old ways looked "primitive" to outsiders. Missionaries and colonial administrators didn't value the oral traditions. By the mid-20th century, the art of reading the swells was dying out. If it weren't for a few dedicated elders and some interested anthropologists, we might have lost the ability to decode these sticks entirely.

Researchers like Dr. Ben Finney and the crew of the Hokule’a proved that "wayfinding"—navigating without instruments—wasn't just luck. It was a rigorous, repeatable science.

The complexity most people miss

The sticks in a Marshall Islands stick chart aren't just straight lines. Notice how some are curved? That’s not an accident or a warp in the wood. A curved stick represents a refracted wave—a swell that is bending as it passes an atoll.

The shells (cowrie or sometimes pieces of coral) indicate the location of islands, but the spacing isn't always "to scale" in a geographical sense. It’s often "to scale" in terms of time or difficulty. If it takes longer to travel between two islands because of a contrary current, the sticks might reflect that rather than the physical distance in miles.

🔗 Read more: Weather for Falmouth Kentucky: What Most People Get Wrong

It’s a functional map, not a literal one. It’s more like a subway map where the lines are straight and clean even though the actual tracks underground are twisting and turning. It’s designed for the user’s brain, not for a surveyor’s ruler.

The legacy in the 21st century

Today, you can buy a Marshall Islands stick chart at markets in Majuro. They’re beautiful. They make great wall art. But very few people living today can actually use one to navigate a boat from Kwajalein to Jaluit.

However, there’s a massive resurgence in pride regarding this technology. It’s a reminder that Pacific Islanders weren't just "drifting" aimlessly until they hit land. They were the greatest blue-water explorers in human history. They were mapping the Pacific while Europeans were still afraid to sail out of sight of the coast.

What we can learn from the sticks

The Marshall Islands stick chart teaches us about observation. In our world, we outsource our "knowing" to Google Maps. We follow the blue dot. If the dot disappears, we’re lost.

The Marshallese navigators did the opposite. They internalized the environment. They became the map.

Actionable ways to explore this history

If you’re fascinated by this indigenous technology, don't just look at a grainy photo online. Here is how to actually engage with the history of the Marshall Islands stick chart:

- Visit the Alele Museum: If you ever find yourself in Majuro, the Alele National Museum is the definitive place to see authentic, historical charts that weren't made for the tourist trade.

- Study Wave Dynamics: To truly understand why the sticks are positioned the way they are, look into "wave interference patterns." It makes the charts go from "cool sticks" to "complex physics."

- Support the Waan Aelõñ in Majel (WAM): This is a program in the Marshall Islands that teaches traditional canoe building and navigation to young people. They are the ones keeping the literal craft alive.

- Check the Smithsonian: The National Museum of the American Indian and the Smithsonian often have digital archives of Polynesian and Micronesian navigational tools with high-resolution details.

The stick chart isn't a relic of a "simpler" time. It’s a testament to a time when humans were more deeply tuned into the natural world than we can currently imagine. It's a reminder that there are many ways to see the world, and some of them don't require a battery.