Honestly, the way we talk about Mars is usually pretty dry. People think of a frozen, dusty desert where dreams of colonization go to die in a vacuum. But everything shifted recently. Mars planet water found isn't just a headline anymore; it's a massive geological reality that’s making NASA scientists lose sleep—in a good way. We aren't talking about a few damp grains of sand or some frost on a crater rim. We are talking about oceans’ worth of liquid water trapped deep within the Martian crust.

It's wild.

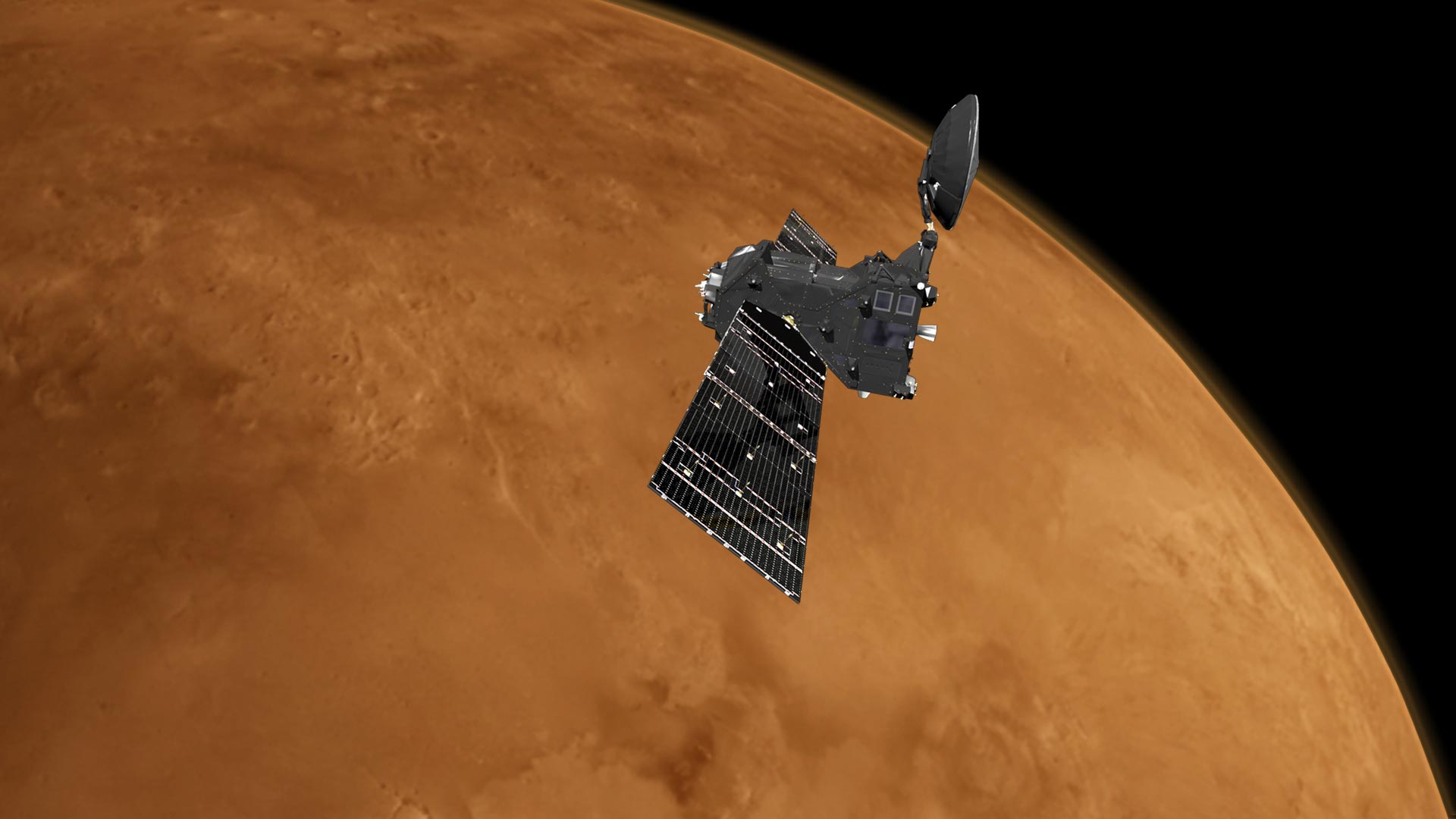

For decades, the narrative was simple: Mars used to have water, it lost its atmosphere, and then it turned into a giant rust ball. But the data from the InSight Lander has basically flipped the script. It turns out the water didn't all just escape into space. A huge chunk of it stayed behind, hiding right under our noses—or rather, miles beneath the landing pads of our rovers.

Where exactly was this Mars planet water found?

You might be wondering how we "found" water without actually digging a hole. We didn't use a shovel; we used "marsquakes." The Insight Lander spent years listening to the pulse of the planet. By measuring how seismic waves move through the ground, researchers like Vashan Wright from UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography were able to map out what the rocks are actually made of.

The waves slowed down in a specific way that only happens when they hit fractured igneous rock saturated with liquid water.

This isn't a surface pond. It’s located in the "mid-crust," roughly 7 to 12 miles (11.5 to 20 kilometers) below the surface. If you took all that water and spread it across the planet, it would create an ocean more than a kilometer deep. That’s a staggering amount of liquid for a planet we thought was a "dead" rock.

🔗 Read more: Arista Networks Market Cap: What Most People Get Wrong

The problem with getting to it

Here is the kicker. While the discovery of Mars planet water found in the crust is scientifically earth-shattering, it’s a bit of a nightmare for future astronauts.

- It is deep. Like, really deep.

- On Earth, drilling a hole 10 miles deep is a massive engineering feat that we’ve barely accomplished (look up the Kola Superdeep Borehole if you want to see how hard it is).

- We don't have the power grid on Mars to run a drill that big.

Basically, we know the "gold" is there, but we don't have the ladder to reach it yet. This puts a bit of a dampener on the immediate plans for "SpaceX Mars Cities" relying on local wells. We are still going to be hunting for near-surface ice at the poles for a long time.

Is there life in that water?

This is the big question. If you have liquid water, a heat source (the Martian core), and minerals, you have the "holy trinity" for biology. On Earth, deep-crust microbes live in similar environments. They don't need sunlight. They "eat" rocks and hydrogen.

If Mars ever had life 3 billion years ago, these deep reservoirs might be the last standing bunkers for Martian microbes. They'd be shielded from the deadly radiation on the surface and the freezing temperatures. It's a cozy, wet basement for life to hide in for eons.

Why the "Atmospheric Escape" theory was only half right

We used to think the solar wind just stripped Mars naked. The sun's radiation supposedly blew the water vapor into the void because Mars lost its magnetic field. While that definitely happened to a lot of the atmosphere, it doesn't account for all the water we know Mars used to have.

The geological evidence—the dry riverbeds and ancient deltas—suggested a much wetter world. The math didn't add up. Where did the rest of it go?

The InSight data suggests the water didn't go up; it went down. As the planet cooled, the water was sucked into the crust like a sponge. This process is called "sequestration." It means the water is technically still there, just locked in a stone cage. It changes how we model planetary evolution entirely.

💡 You might also like: Apple MacBook Air M4: What Most People Get Wrong

What most people get wrong about Martian water

People hear "water on Mars" and think of the Recurring Slope Lineae (RSL). Those are the dark streaks on crater walls that appear in the summer. For a while, we thought those were salty brine flows.

But lately, the consensus has shifted toward them being dry dust avalanches. It was a bit of a letdown. That's why this new discovery is so much more significant. It’s not a seasonal smudge; it’s a permanent, massive reservoir.

Nuance: Is it actually "water"?

We should be clear—you probably wouldn't want to drink this stuff straight. It’s likely a very salty brine. Given the minerals present in Martian soil, like perchlorates, it’s probably a chemical soup that would be toxic to humans without serious desalination and filtering.

The next steps for Mars exploration

Since Mars planet water found in the deep crust is currently out of reach, the focus is shifting back to the "easy" stuff. We need to find "accessible" water.

- Subsurface Ice Mapping: NASA’s Phoenix lander already tasted ice just inches below the dirt near the north pole.

- Glacial Buried Deposits: In mid-latitude regions like Arcadia Planitia, there are massive glaciers covered by just a few feet of dust.

- The Perseverance Rover: It’s currently bagging samples in Jezero Crater that might contain minerals formed in the presence of that deep water billions of years ago.

The discovery of the deep reservoir basically acts as a "proof of concept" for the planet's history. It tells us that Mars was once a world of oceans, and it didn't just lose its lunch to the sun. It kept its secrets buried.

Actionable Insights for Space Enthusiasts and Researchers

If you're following the progress of Martian exploration, here is what you should actually be watching for over the next few years.

Watch the Mars Sample Return (MSR) mission. This is the big one. While we’ve found water through seismic data, we need physical rocks from Jezero Crater to see the "fingerprints" of that water. If those rocks show specific carbonate minerals, we can confirm how long that water stayed on the surface before sinking.

Follow the development of "In-Situ Resource Utilization" (ISRU) tech. Since we can't drill 10 miles down, companies are working on "micing" ice from the top 10 feet of soil. Look for updates on NASA’s Subsurface Water Ice Mapping (SWIM) project. They are literally making a "treasure map" for where humans should land to stay hydrated.

Check out the seismic data from the Mars InSight mission archives. It’s public. You can actually hear the "pings" of the planet that led to this discovery. It’s a reminder that sometimes, to see what’s in front of us, we have to listen to the ground beneath us.

✨ Don't miss: How Do I Contact Facebook by Telephone: The Truth About Those 800 Numbers

The discovery of massive liquid water deep in the Martian crust has fundamentally changed the roadmap. We aren't looking for a dead rock anymore. We are looking at a planet that has been holding onto its most precious resource for billions of years, waiting for us to figure out how to reach it.

Monitor the upcoming International Mars Ice Mapper mission. This is a planned orbiter that will use specialized radar to find the most "drillable" water ice. This is the bridge between the "deep water" we found and the "drinking water" we need. Stay focused on the mid-latitude regions of Mars, as these are the likely spots for the first human base camps due to the balance of solar power and accessible ice.