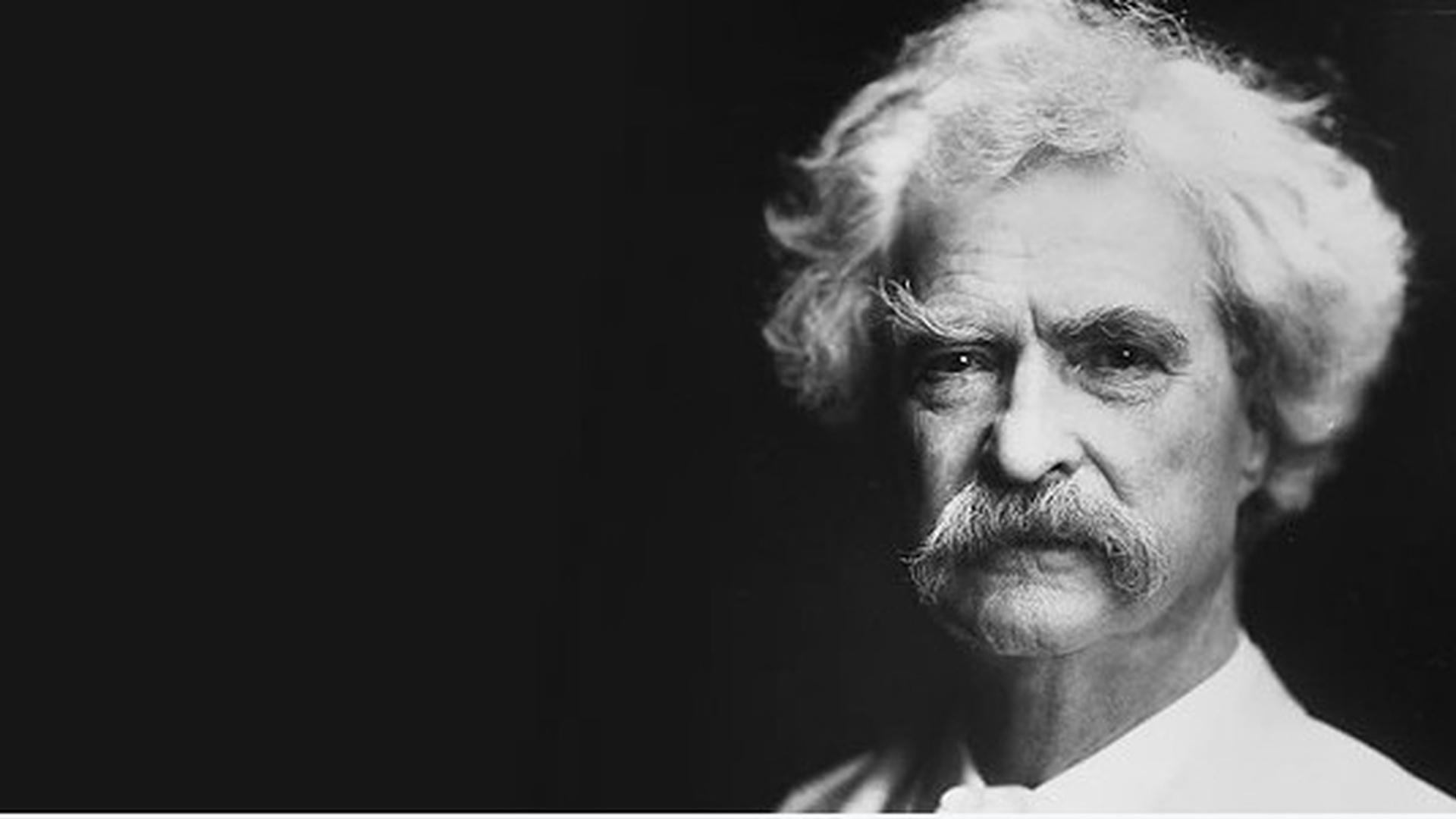

Mark Twain was the funniest man in America, right? The white suit, the cigar, the wit that could take the paint off a fence—that’s the version we get in history class. But there’s a version of Samuel Clemens that most people never meet. It’s the one who sat in his study late at night, convinced that every human being on the planet is just a heartless, programmed machine.

In 1906, he finally let the world see this side of him. Kind of. He published Mark Twain What Is Man anonymously at first. Only 250 copies. He was terrified of what it would do to his reputation, but he couldn't keep the thoughts locked in his desk anymore.

The "Gospel" of the Machine

The book isn't a novel. It’s a Socratic dialogue between an "Old Man" and a "Young Man." Honestly, it reads a bit like a grumpy professor trying to ruin a student's afternoon. The Old Man (who is clearly Twain) argues that humans have zero free will. None. Zip.

Twain’s core argument in What Is Man? is that the human mind is a machine. It reacts to outside influences. It follows its temperament. You don't "choose" to be brave or kind any more than a coffee mill chooses to grind beans. You just do what your internal machinery and external training dictate. It's a heavy concept for a guy who wrote about boys playing hooky on the Mississippi.

Why he called it a "Desolating Doctrine"

Twain didn't think this was a happy realization. He actually called his own philosophy "desolating." He knew it took the "heroism" out of humanity. If you save a drowning child, Twain argues in the text, you aren't doing it for the child. You’re doing it to satisfy your own "Master Impulse"—the need to feel peace of mind and avoid the personal torment of watching someone die.

It’s psychological egoism at its most cynical.

He basically says:

- No one ever originates a thought; they just recycle outside influences.

- The only motive for any action is to secure your own self-approval.

- Free will is an illusion because you will always follow the strongest impulse in your mind at that moment.

Is Mark Twain What Is Man still relevant?

You’d think a 120-year-old philosophy book would be dusty and forgotten. But here’s the thing: modern neuroscience is kinda backing him up. We talk about "brain chemistry" and "neural pathways" today. Twain just called it "the machine."

When we look at how algorithms influence our choices or how our upbringing "programs" our reactions, we're basically reciting Twain's dialogue. He was exploring the "nature vs. nurture" debate before those terms were even popular.

The public's reaction (or lack thereof)

When the book finally went public under his name in 1910, right after his death, people were shocked. The New-York Tribune ran a massive feature on it. Critics called it dark and anti-religious. They couldn't reconcile the man who created Tom Sawyer with the man who claimed mother-love is just a form of "self-satisfaction."

But Twain didn't care by then. He was gone. He’d spent decades honing these arguments, revising the manuscript over and over since the late 1870s. He knew it would be his "Bible," even if the rest of the world hated it.

What most people get wrong about the book

A lot of readers think Twain was just being a "humorist" or that this was a satire. It wasn't. This was his "Gospel." He genuinely believed this stuff.

He didn't think being a machine was an excuse to be a jerk, though. In a section titled "Admonition," he argues that since we are products of our training, we have a responsibility to "train our ideals upward." Basically, if you know you’re a machine, you might as well try to put yourself in environments that make you a better machine.

🔗 Read more: Jon Stewart Pizza Rant: Why the Casserole Comments Still Burn

It’s a weirdly pragmatic twist for such a gloomy book.

How to actually read it today

If you want to dive into What Is Man?, don't expect Huckleberry Finn. Expect a fight. It’s a short read, maybe 60 to 100 pages depending on the edition, but it’s dense. It’ll make you question why you do anything. Why did you buy that coffee? Why are you reading this article? According to Twain, you didn't have a choice. Your "machine" just landed here.

To get the most out of it, try this:

- Read it as a dialogue. Imagine Twain himself as the Old Man, pacing around a room with a cigar, trying to convince a younger, more idealistic version of himself.

- Look for the "Master Impulse." Next time you do something "selfless," stop and ask if Twain was right. Did you do it for them, or for your own peace of mind?

- Compare it to modern psychology. Look at how his ideas on "outside influence" mirror what we now know about social conditioning.

Twain might have been a cynic, but he was a deeply honest one. He didn't want to lie to himself anymore, and What Is Man? was his way of stripping away the masks we all wear.

📖 Related: David Bowie’s Ashes to Ashes Lyrics: Why Major Tom Had to Die

Next Steps for You:

Pick up a copy of What Is Man? and Other Essays. It’s often packaged with "The Lowest Animal," which is another blistering critique of humanity that pairs perfectly with this dialogue. If you’re a fan of Twain’s fiction, reading this will completely change how you view characters like Huck or Pudd'nhead Wilson—you'll start seeing them as the "machines" Twain always intended them to be.