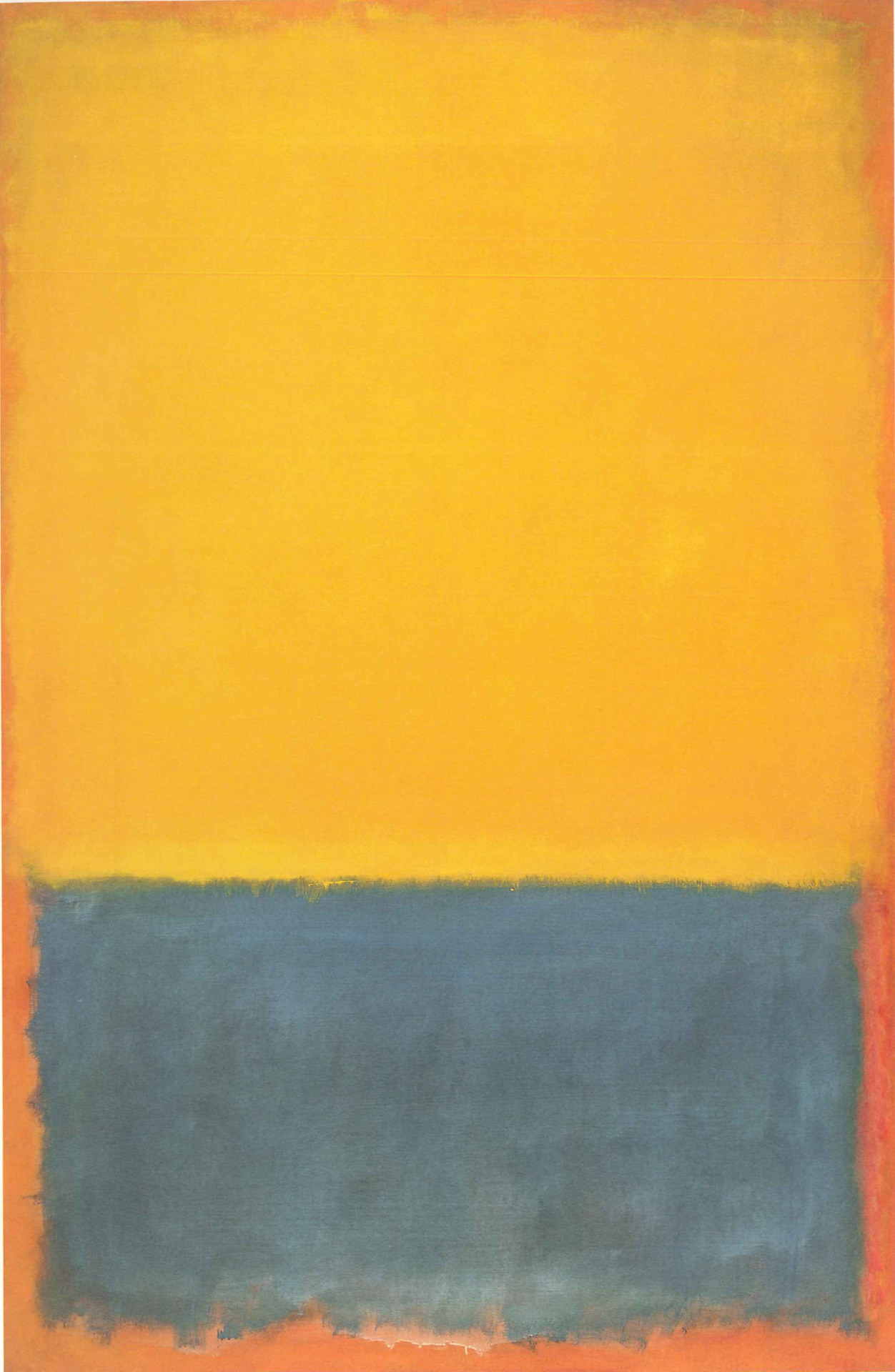

You’ve probably seen it. Maybe on a Pinterest board for minimalist lofts or in a textbook about mid-century New York. Two massive, vibrating blocks of color—one a sunshine yellow, the other a deep, bottomless blue.

It looks simple. Some people say it looks too simple. "My kid could do that," is the classic refrain from the skeptic leaning over the museum velvet rope. But honestly? They couldn't. Not like this.

Mark Rothko's Untitled (Yellow and Blue), painted in 1954, is a nine-foot-tall monster of a canvas that recently made headlines again. In late 2024, it sold at Sotheby’s Hong Kong for about $32.5 million. Interestingly, that was a huge drop from its 2015 price tag of $46.5 million. Does that mean Rothko is "out"? Hardly. It just means the art market is as moody as the paintings themselves.

But if you’re looking at this painting and only seeing "yellow and blue," you’re missing the entire point of why Rothko spent his life in a dusty studio mixing pigments until his lungs gave out.

📖 Related: Why Pictures of Hair Cuts Look Better on Your Phone Than on Your Head

It’s not about the colors (really)

Rothko famously hated being called a "colorist." If you told him his color combinations were beautiful, he’d probably walk away from you. He once said, "If you are only moved by color relationships, you are missing the point."

So, what is the point?

He wanted to hit you in the gut. He was trying to translate "the big emotions"—tragedy, ecstasy, doom—into something you could see. The yellow isn't just yellow; it’s a flickering, unstable light. The blue isn't just blue; it’s an abyss. When they sit next to each other, they don’t just "match." They vibrate. They fight.

The technical "magic" you can't see on a screen

If you’ve only seen Yellow and Blue on a phone, you haven't really seen it. Rothko didn't just slap paint on. He layered thin, watery washes of oil paint, sometimes so thin they were like stained glass.

- Luminosity: He’d paint a dark layer, then a bright one, then another dark one. Light travels through these transparent layers, hits the white canvas, and bounces back. It makes the painting look like it’s glowing from the inside.

- The Edges: Look at where the yellow meets the blue. It’s not a straight line. It’s fuzzy. It’s "breathing." Rothko wanted those rectangles to feel like they were hovering in space, not stuck to a flat surface.

- The Scale: The painting is nearly eight feet tall. That’s intentional. He wanted it to be bigger than you so you couldn't "view" it from a distance like a window. He wanted you to be inside it.

The weird, wealthy life of a masterpiece

The history of this specific 1954 painting is a wild ride. It’s passed through some of the most famous hands in the world.

For a long time, it belonged to Paul Mellon and his wife Bunny—ultra-wealthy American philanthropists. Later, it moved into the collection of François Pinault, the billionaire who owns Gucci and Yves Saint Laurent.

Then things got a bit "Wolf of Wall Street." At one point, it was owned by Jho Low, the fugitive financier at the heart of the 1MDB scandal. It was even tied up in a massive, messy divorce case involving an Azerbaijani-Russian billionaire.

Basically, this painting has seen more drama in a few decades than most people see in a lifetime. It’s a bit ironic, considering Rothko created these works for "pockets of silence" and meditation.

✨ Don't miss: Converting 19 C to F: Why This Specific Temperature Is Everywhere

Why people get frustrated with Rothko

Let’s be real: Rothko is polarizing.

There’s a whole group of people who think the "Color Field" movement is a giant prank played by the elite to make themselves feel smart. They see a yellow block and a blue block and they see a lack of skill.

But if you look at Rothko's early work, he could paint "real" things perfectly well. He did subways, people, and mythological scenes. He chose to strip all of that away. He thought figures and objects were just distractions. He wanted the rawest possible connection between the artist and the viewer.

Kinda like how a song can make you cry without having any lyrics. That’s what he was going for with paint.

How to actually "look" at a Rothko

If you ever find yourself in front of a real Rothko (the National Gallery of Art in D.C. has a great collection), don't just walk past it.

- Get Close. Rothko actually said the ideal viewing distance is 18 inches. That’s closer than most museums will let you get without an alarm going off, but get as close as the guard allows.

- Stay Still. This isn't a "glance and go" situation. Give it at least three minutes. Your eyes need time to adjust to the subtle layers.

- Notice the "Flash." Because of the way he layered colors, you’ll eventually start to see colors that aren't actually there—ghostly greens or purples flickering at the edges of the yellow and blue.

- Check your ego. Stop trying to figure out "what it is." It isn't a sunset. It isn't a flag. It’s just... a feeling.

Actionable insights for your own space

You don't need $32 million to bring a bit of Rothko’s philosophy into your life. Whether you’re an artist or just someone decorating a living room, there are lessons here:

- Embrace the "Breathing" Edge: When painting a wall or a piece of furniture, don't worry about perfect, taped-off lines. A slightly soft edge feels more organic and less "plastic."

- Layering for Depth: If you're DIY-ing some art, try using glazes or thinning your acrylics with water. Multiple thin layers always look more expensive and "deep" than one thick coat of flat paint.

- Color as Mood: Stop thinking about what colors "go together" according to a chart. Think about how they make you feel. High-contrast pairings (like yellow and blue) create energy and tension. Low-contrast pairings (like dark blue and purple) create calm.

- Scale Matters: If you have a small room, putting one massive piece of art in it actually makes the room feel bigger and more intimate, rather than cluttering it with ten small frames.

Rothko's Yellow and Blue isn't just a status symbol for billionaires. It’s a reminder that sometimes, the most profound things are the ones we can't quite put into words. It’s an invitation to just sit down, shut up, and feel something for a change.