If you’ve ever spent time looking at a Great Hammerhead (Sphyrna mokarran) and thought it looked like a biological accident, you aren't alone. It’s a weird fish. Honestly, it’s one of the most specialized predators on the planet, but when people start looking for marine biology notes on whale hammerhead sharks, things get a bit confusing. There is actually no such thing as a "whale hammerhead." You’ve got Whale Sharks, and you’ve got Hammerheads. They are two completely different beasts. But, because they both represent the "megafauna" of the shark world, they often get lumped together in search bars and student notebooks.

Let’s get the record straight right away.

The Hammerhead family (Sphyrnidae) is a group of nine species, while the Whale Shark (Rhincodon typus) is a lone branch of the carpet shark order. They don't interbreed. They don't look alike. They don't even hunt the same way. One is a giant filter feeder that basically acts like a vacuum for plankton; the other is a high-speed pursuit predator that uses its face as a weapon. If you're building out your study materials or just curious about the apex predators of the deep, you have to treat these two as opposites.

Why Marine Biology Notes on Whale Hammerhead Sharks Often Get Mixed Up

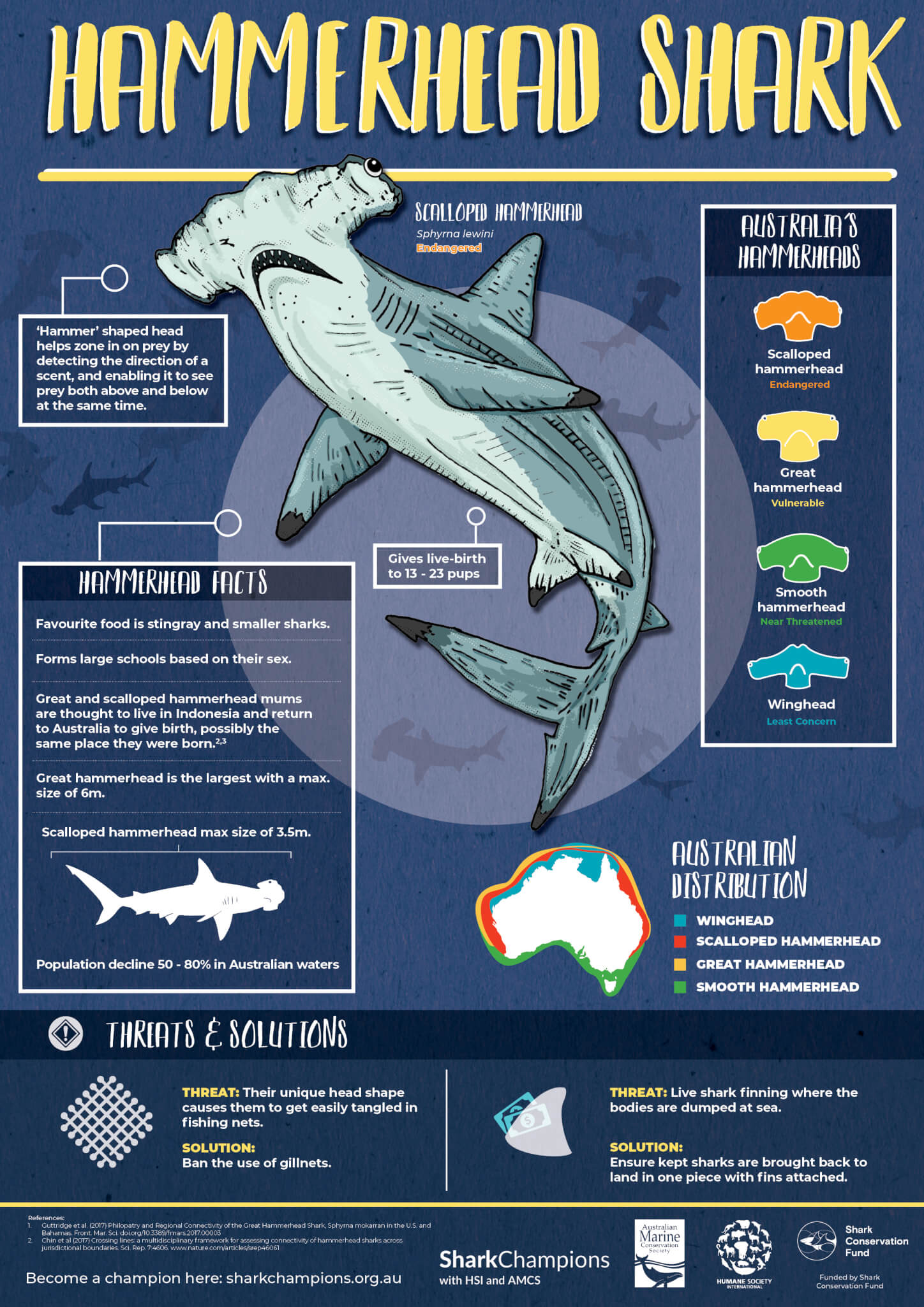

The confusion usually stems from the Great Hammerhead’s size. It can reach lengths of 20 feet. That's "whale-sized" in the eyes of a casual snorkeler. In most marine biology notes on whale hammerhead sharks, the focus is actually on the Great Hammerhead because of its sheer dominance. It’s the heavyweight champion of the hammerhead world.

Think about the cephalofoil—that T-shaped head. It isn't just for show. It acts like a bow plane on a submarine. When a hammerhead wants to turn, it doesn't just use its fins. It tilts that massive head and generates lift, allowing for some of the tightest turning circles in the animal kingdom. If you’re a stingray, this is your worst nightmare. You can’t outmaneuver them.

The Cephalofoil: A Biological Swiss Army Knife

Most students assume the head is all about vision. That’s only half the story. Yes, having eyes on the ends of a wide bar gives them 360-degree vertical vision. They can see what’s above them and below them at the same time. But the real secret sauce is the Ampullae of Lorenzini. These are tiny pores that detect electromagnetic fields. Because the hammerhead has such a wide "hammer," it has more surface area for these sensors. It’s basically a wide-band metal detector.

📖 Related: Coach Bag Animal Print: Why These Wild Patterns Actually Work as Neutrals

They sweep the seafloor like a hobbyist at the beach looking for lost rings.

Except they aren't looking for jewelry. They’re looking for the heartbeat of a stingray buried under six inches of sand. When they find one, they don't just bite. They use that flat head to pin the ray to the bottom. They literally "hammer" their prey into submission before taking a bite. It’s brutal. It’s efficient. It’s why they’ve survived for millions of years.

Comparing the Giants: Hammerheads vs. Whale Sharks

If you’re comparing these in your research, you’re looking at two different evolutionary paths. The Whale Shark is the largest fish in the sea, sometimes hitting 40 feet or more. It’s a "Filter Feeder." It moves slow. It’s gentle. It doesn't have the serrated, razor-sharp teeth of the Great Hammerhead.

Hammerheads are "Carcharhiniformes." That’s a fancy way of saying they are ground sharks. They have a high metabolism. They have to move constantly to breathe (obligate ram ventilation). If a hammerhead stops swimming, it sinks and suffocates. Whale sharks can actually hang out vertically in the water column and gulp water to breathe, though they mostly swim to feed.

- Great Hammerhead: 20 feet max, 500-1,000 lbs, eats rays and other sharks.

- Whale Shark: 40+ feet, 20,000+ lbs, eats plankton and krill.

- Social Behavior: Hammerheads (especially Scalloped Hammerheads) are famous for schooling in the hundreds. Whale sharks are mostly solitary nomads.

It’s interesting to note that while Hammerheads are intensely social at times, we don't really know why. Dr. Yannis Papastamatiou from Florida International University has done some incredible work tracking shark movements. He’s found that these sharks have "social preferences." They aren't just bumping into each other; they choose who they hang out with. That’s a level of intelligence most people don't attribute to a fish.

👉 See also: Bed and Breakfast Wedding Venues: Why Smaller Might Actually Be Better

The Tragedy of the Fin

We can't talk about hammerheads without talking about how fast they're disappearing. It’s grim. Because of that massive dorsal fin—the one that sticks out of the water like a movie prop—they are highly targeted for the shark fin trade.

Great Hammerheads are currently listed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN.

Their biology makes them especially vulnerable. Unlike some sharks that are "tough" and can survive being caught and released, hammerheads are high-strung. They fight so hard when they’re hooked that their body chemistry turns acidic. They often die of physiological stress shortly after being released. This is called "post-release mortality," and it's a huge problem for conservationists. If you're a marine biology student, this is the area where the most research is needed right now. How do we catch them for tagging without literally stressing them to death?

New Research on Deep-Sea Diving

A really cool piece of news that recently hit the marine biology world involves the "breath-holding" behavior of Scalloped Hammerheads. We used to think they just liked warm water. But researchers like Mark Royer have found that they dive deep—over 2,500 feet—into freezing water to hunt.

How do they stay warm? They close their gills.

✨ Don't miss: Virgo Love Horoscope for Today and Tomorrow: Why You Need to Stop Fixing People

They basically hold their breath to keep their body heat in while they're in the "twilight zone." It’s a crazy strategy. It’s like a human jumping into an ice bath and holding their breath to keep their core temperature up. This discovery completely changed how we map their "critical habitat." If they are using the deep ocean as much as the surface, we need to protect both.

Real-World Applications for Your Notes

If you are actually compiling marine biology notes on whale hammerhead sharks for a project or a dive certification, you should focus on the "Bimini Connection." Bimini, in the Bahamas, is one of the only places on Earth where Great Hammerheads are reliably found in shallow water during the winter months.

This is where the legendary Shark Lab (Bimini Biological Field Station) does its best work. Founded by the late Dr. Sonny Gruber, this lab has shaped almost everything we know about how these sharks move and live. If you want "human-quality" insights, look at their published papers. They’ve proven that hammerheads have "home ranges." They aren't just aimless wanderers. They have a map in their head.

Key Anatomical Features to Memorize:

- The Cephalofoil: Provides lift and housing for sensory organs.

- Dorsal Fin: Unusually tall and sickle-shaped in Great Hammerheads.

- Teeth: Triangular and heavily serrated for sawing through tough prey.

- Nictitating Membrane: A "third eyelid" that protects the eye during an attack (though hammerheads actually rotate their eyes back instead).

Honestly, the hammerhead is a bit of a mystery still. We don't know exactly where they mate. we don't know exactly where they give birth. We just see the "finished product" cruising past a reef. For a marine biologist, that’s exciting. It means there’s still plenty to discover.

Actionable Next Steps for Enthusiasts

If you’re serious about learning more or even helping save these animals, don't just read about them. The data is changing every year.

- Follow Real Researchers: Check out the work being done by the Beneath the Waves foundation or the Bimini Shark Lab. They post real-time tracking data that is way more interesting than a textbook.

- Use Citizen Science: If you're a diver, you can upload your shark photos to Wildbook for Sharks. They use AI to identify individual sharks based on their markings or fin shapes. You can actually help track a shark's migration from your laptop.

- Check the IUCN Red List: Don't take a blog's word for it. Look up the specific species of hammerhead (Scalloped, Great, Smooth, Bonnethead) to see their current population status. It varies wildly between species.

- Avoid Shark Products: This seems obvious, but shark squalene is in a lot of cosmetics and health supplements. Read the labels. If it doesn't say "plant-derived," it might be shark.

Hammerheads are the architectural marvels of the ocean. They are fast, smart, and weird-looking in the best way possible. Whether you're a student or just someone who loves the sea, understanding that there’s no such thing as a "whale hammerhead" is the first step toward actually respecting the complex reality of these two very different giants. Keep your notes organized, but keep your mind open—marine biology is a field where "facts" get updated all the time.