Everyone thinks they know the story. Two geniuses, a drafty shed in Paris, and a glowing test tube. It's the standard textbook version of Marie and Pierre Curie. But honestly, the real story is much grittier, weirder, and way more tragic than the polished version we got in school.

They weren't just scientists. They were outsiders. Marie—born Maria Skłodowska—was a Polish immigrant living on tea and bread in a garret. Pierre was a brilliant physicist who had basically given up on the academic establishment because he couldn't stand the politics. When they met in 1894, it wasn't some cinematic lightning bolt. It was a conversation about a lab space. Pierre had a little extra room at the School of Industrial Physics and Chemistry, and Marie needed a place to study the magnetic properties of steel.

What the Textbooks Miss About the Discovery of Radium

The work was brutal. You've probably heard they discovered Polonium and Radium, but do you realize the physical toll it took? They weren't working with high-tech equipment. They were literally stirring boiling vats of pitchblende residue with iron rods that were almost as heavy as they were.

They spent four years in what was essentially a leaky, unventilated wooden shed. Wilhelm Ostwald, a Nobel laureate who came to see their "lab," described it as a cross between a stable and a potato cellar. He actually thought he was being pranked. He said, "If I had not seen the worktable with the chemical apparatus, I would have thought it a practical joke."

It's actually kind of wild when you think about it.

They were refining tons of ore to find a fraction of a gram of radium. Marie once wrote about the "precious particles" that would glow in the dark of their shed like "faint, fairy lights." She didn't realize those fairy lights were slowly destroying their DNA.

The Pitchblende Problem

Why pitchblende? Marie had this hunch. She noticed that this specific mineral was way more radioactive than the pure uranium she was testing. This led to a logical, if exhausting, conclusion: there had to be something else in there. Something way more powerful.

The couple refused to patent their processes. They could have been billionaires. Seriously. Radium became the most expensive substance on earth, and they just gave the instructions away for free. Pierre's logic was simple: it was a "pure science" discovery. If you patent it, you slow down the progress of medicine.

🔗 Read more: EU DMA Enforcement News Today: Why the "Consent or Pay" Wars Are Just Getting Started

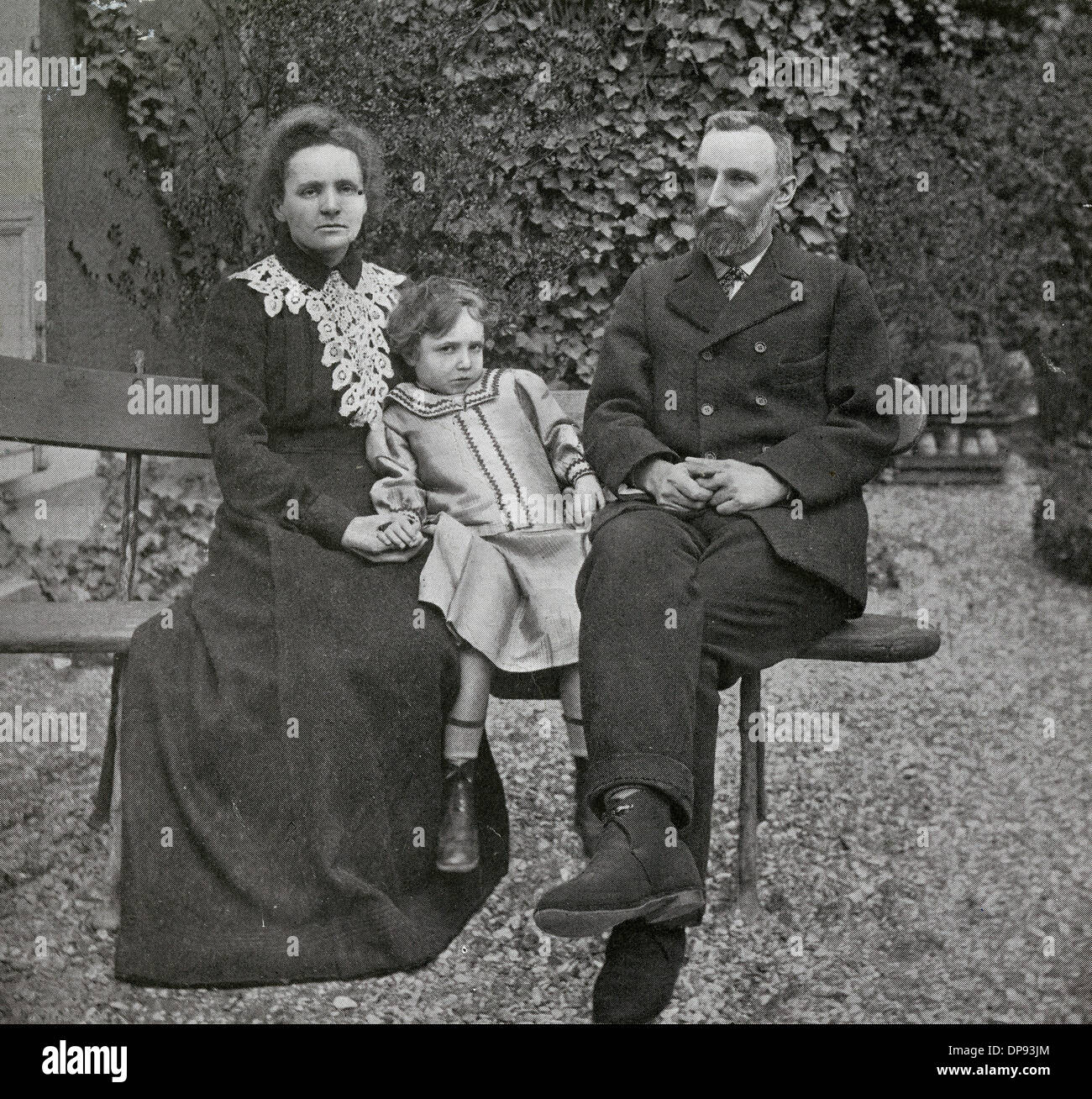

Why the Marie and Pierre Curie Partnership Was Unique

In the late 19th century, women in science didn't really exist in the eyes of the French Academy. Pierre knew this. He was incredibly protective of Marie’s intellectual ownership. When the French Academy of Sciences nominated Pierre and Henri Becquerel for the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1903, they intentionally left Marie out.

Pierre didn't just send a polite letter. He staged a mini-revolt. He told the committee that a Nobel Prize for the discovery of radioactivity that didn't include Marie was a joke. He insisted she be included. Because of his stubbornness, Marie became the first woman to win a Nobel.

But it wasn't all harmony and Nobel galas.

Pierre was suffering. By 1903, his legs were constantly aching. He had violent fits of pain. We know now it was radiation sickness, but back then, they blamed "rheumatism" or nerves. He was so tired he could barely get dressed some mornings. Marie wasn't doing much better. She lost weight constantly and her fingers were permanently scarred and peeling from handling raw radium.

The Tragedy of 1906 and the Scandal That Followed

The partnership ended in the most mundane, horrific way possible. It wasn't radiation that killed Pierre. It was a rainy Thursday in Paris. On April 19, 1906, Pierre was crossing the Rue Dauphine when he slipped and fell under the wheels of a heavy horse-drawn wagon. He died instantly.

Marie was devastated. She became a "black-clad widow" for the rest of her life, but she also became a powerhouse. She took over Pierre’s teaching post at the Sorbonne—the first woman to ever do so.

Then things got messy.

💡 You might also like: Apple Watch Digital Face: Why Your Screen Layout Is Probably Killing Your Battery (And How To Fix It)

Around 1910, Marie had an affair with Paul Langevin. He was a former student of Pierre’s and a brilliant physicist in his own right. He was also married. When the French press got hold of their love letters, the public turned on her. They called her a "foreign Polish home-wrecker." A mob actually surrounded her house.

While this scandal was peaking, she got a telegram. She had won a second Nobel Prize, this time in Chemistry. The Swedish Academy actually tried to tell her not to come to the ceremony because of the scandal. Marie’s response was legendary. She basically told them that her scientific work had nothing to do with her private life and she was coming to get her prize.

The Little Curies: Radioactivity on the Front Lines

If you want to see the real impact of Marie and Pierre Curie, look at World War I. Marie realized that soldiers were dying of shrapnel wounds because surgeons couldn't find the metal inside their bodies.

She didn't stay in her lab.

She developed "Petites Curies"—mobile X-ray units. She learned to drive, learned basic auto mechanics, and drove these vans to the front lines. She even brought her teenage daughter, Irène, along. They gave X-rays to over a million soldiers. Marie even tried to donate her gold Nobel medals to the war effort, but the French National Bank refused to melt them down.

Why We Still Care Today

We are still living in the world they built. Every time someone gets a PET scan or undergoes radiation therapy for cancer, they are using technology that traces directly back to that shed in Paris.

But there’s a dark side. Marie died in 1934 from aplastic anemia. Her body was so radioactive she had to be buried in a lead-lined coffin. Even today, her notebooks—the ones she used in the 1890s—are kept in lead-lined boxes at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. If you want to look at them, you have to wear a hazmat suit and sign a liability waiver.

📖 Related: TV Wall Mounts 75 Inch: What Most People Get Wrong Before Drilling

The radioactivity will last for another 1,500 years.

How to Apply the Curie Mindset

- Focus on the "Why" not the "What": The Curies succeeded because they were obsessed with the anomaly (why is pitchblende so active?) rather than just repeating known experiments.

- Intellectual Integrity: Pierre's refusal to patent radium is a case study in "Open Source" philosophy before the term existed. Sometimes, the legacy is worth more than the equity.

- Resilience through Scarcity: They didn't wait for a "perfect" lab. They worked in a shed. Stop waiting for better tools and start using what you have.

The story of Marie and Pierre Curie is often sanitized into a boring tale of two nerds. In reality, it was a saga of immigration, sexism, physical pain, scandalous love, and a relentless drive to understand the very fabric of the universe. They didn't just discover elements; they changed what we thought was possible for a human being to endure for the sake of knowledge.

To truly understand the science, you have to look at the scars on their hands. That's where the real story lives.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge

If you're looking to go beyond the basic biography, your next move should be visiting the Musée Curie in Paris (if you're ever in the 5th arrondissement). It’s located in the very lab where Marie worked for decades.

Alternatively, read Marie's own biography of Pierre. It is surprisingly raw and gives a perspective you won't find in modern textbooks. You should also check out the 2011 archival release of Marie’s digitized letters through the American Institute of Physics; they provide a much more human, less "saint-like" view of her daily struggles with fame and grief.