You’ve probably seen the flag. Red, black, and green. It’s a symbol of pride now, but back in the roaring twenties, it was the heartbeat of a movement that terrified the U.S. government. At the center of it all was a man named Marcus Garvey. He wasn't just a speaker; he was a guy who wanted to build a global economy for Black people from scratch.

His big swing? The Black Star Line.

It sounds like a movie plot. A Jamaican immigrant arrives in Harlem, starts a massive organization called the UNIA, and decides the best way to fight racism isn't just through protests, but through shipping. He wanted a fleet of vessels owned and operated by Black people. Ships that would carry cargo between America, the Caribbean, and Africa.

Honestly, the ambition was staggering.

But if you look at the history books, the story usually stops at "he failed and went to jail." That’s a massive oversimplification. The real story is a messy, fascinating mix of visionary genius, terrible business deals, and a very young J. Edgar Hoover doing everything in his power to burn the whole thing down.

Why a Shipping Line?

Garvey wasn't interested in asking for a seat at the table. He wanted to build a new house. He looked at the White Star Line (the company that owned the Titanic) and basically said, "We can do that too."

In 1919, the world was a different place. Black travelers were treated like second-class citizens on existing ships. They were often restricted to the worst decks or denied service entirely. Garvey saw a business opportunity here. If he could provide dignified travel and a way for Black farmers in Jamaica to sell their produce directly to Black grocers in New York, he’d create a self-sustaining loop.

Economic independence. That was the goal.

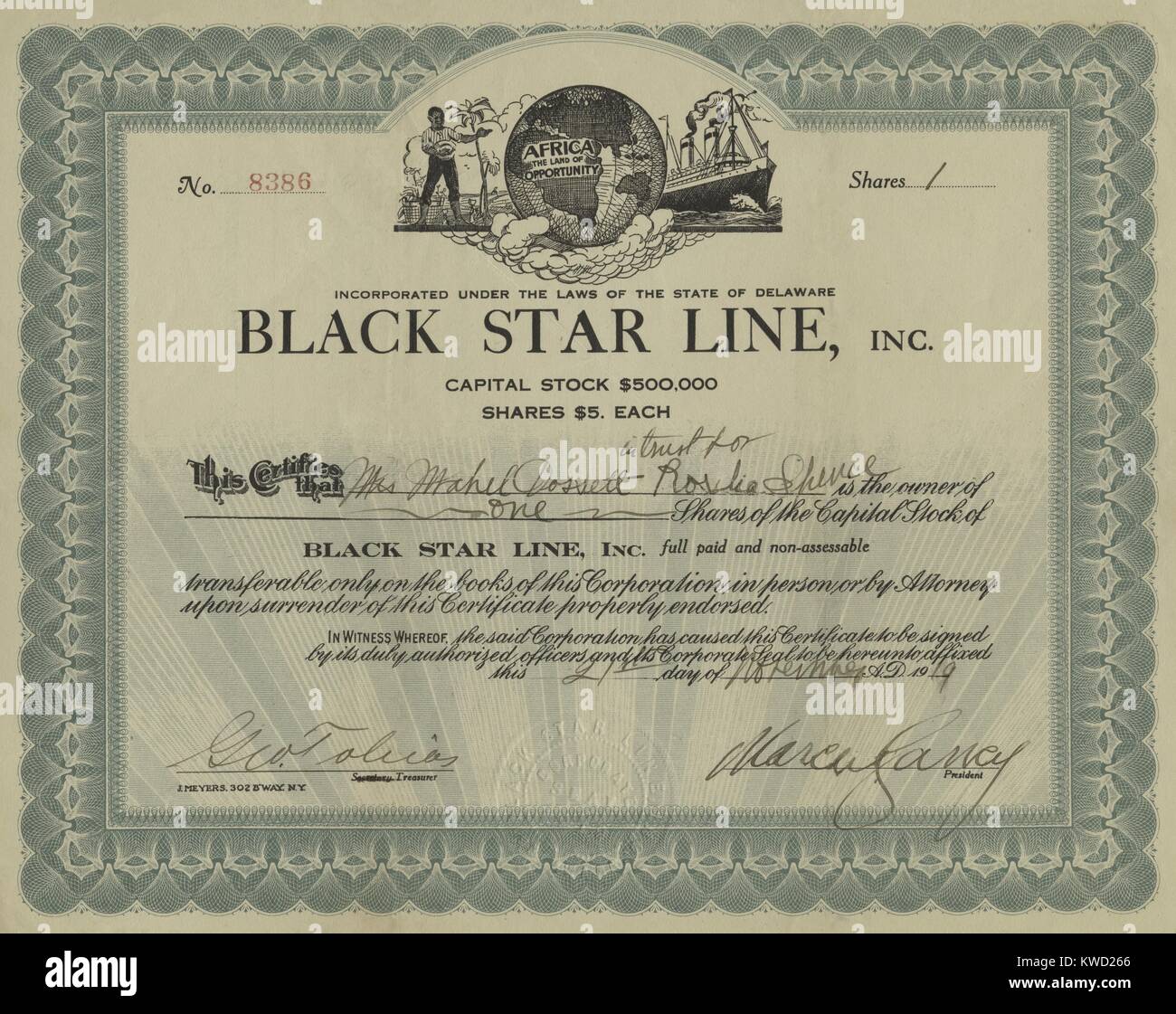

He incorporated the Black Star Line in Delaware with a capitalization of $500,000. That’s roughly $9 million today. He didn't go to big banks. He went to the people. He sold shares for $5 each.

The People’s Investment

Imagine being a janitor or a maid in 1920. You have five dollars. That’s a lot of money—maybe a week's wages. You give it to Garvey because for the first time, someone is telling you that you can own a piece of a steamship.

People didn't just buy stock; they bought hope. They bought certificates that represented a future where they weren't just laborers, but owners. Thousands of people poured their life savings into the venture.

The Ships That (Mostly) Didn't Sail

This is where the business side of things gets... complicated. Garvey was a master of the stage, but he wasn't a master of the sea. Or engineering. Or maritime law.

The first ship was the SS Yarmouth. Garvey wanted to rename it the Frederick Douglass.

The problem? It was a 32-year-old "relic" that had been used to carry coal.

The UNIA paid $165,000 for it, which was a massive overpayment. To make matters worse, the people selling it knew Garvey was desperate. They fleeced him. On its very first voyage, the ship had mechanical failures. Later, it set off with a cargo of whiskey just before Prohibition kicked in. It was a disaster. The ship was eventually sold for scrap for a tiny fraction of what they paid.

Then came the SS Shadyside.

It was a Hudson River excursion boat. It did some summer trips, which were great for PR, but it wasn't built for the ocean. One winter, it literally sank while at anchor because of ice damage. Total loss.

💡 You might also like: Trump Purposely Crashing Stock Market: What Most People Get Wrong

Finally, there was the SS Kanawha (renamed the Antonio Maceo).

It was a luxury yacht, not a cargo ship. It looked pretty in photos, but it was a mechanical nightmare. On one trip, a boiler exploded and killed a crew member.

Mismanagement or Sabotage?

It’s easy to say Garvey was a bad businessman. And yeah, he made some truly questionable hires. He hired white officers who often didn't want the ships to succeed. He hired a captain, Joshua Cockburn, who later admitted to taking "kickbacks" on the purchase price of the ships.

But you can't talk about the failure without talking about the BOI (the precursor to the FBI).

J. Edgar Hoover was obsessed with Garvey. He saw a powerful Black man with millions of followers as a "radical" threat. The government didn't just watch; they infiltrated. They sent agents like James Wormley Jones to get inside the UNIA. There are documented claims of agents throwing foreign matter into the fuel and engines of Black Star Line ships to cause breakdowns.

The goal was simple: make the business fail so the movement would die.

The Mail Fraud Case

In 1922, the government finally found their "gotcha."

The Black Star Line had been advertising a fourth ship, the SS Phyllis Wheatley. They even sent out brochures with a picture of the ship.

The problem? They didn't actually own it yet. They were in negotiations to buy it, but the deal hadn't closed.

Technically, soliciting investment for a ship you don't own is mail fraud.

Garvey was arrested. The trial was a circus. He insisted on defending himself, which honestly was a mistake. He was a great orator, but he didn't know the rules of a courtroom. He ended up annoying the judge and the jury.

He was convicted in 1923 and sentenced to five years. In 1927, President Calvin Coolidge commuted his sentence and immediately deported him to Jamaica. He never saw his movement reach those heights again.

What Most People Get Wrong

People often call the Black Star Line a "scam."

A scam is when someone takes your money with no intention of providing a service. Garvey wanted those ships to sail. He wanted them to reach Africa. He spent every cent he raised on ships and repairs. He just didn't have the technical expertise to navigate the cutthroat shipping industry of the 1920s.

He was also fighting a war on two fronts.

- The Government: As we mentioned, the BOI was actively sabotaging him.

- Internal Rivals: He clashed with other Black leaders like W.E.B. Du Bois. Du Bois called Garvey "the most dangerous enemy of the Negro race." They disagreed on everything from integration to the "Back to Africa" plan.

It’s also important to note that the "Back to Africa" thing is often misunderstood. Garvey didn't think every Black person in America should leave. He wanted to establish a strong, independent African nation (starting with Liberia) that could act as a protector and trade partner for the diaspora. He wanted Black people to have the option of a homeland.

The Legacy (It’s bigger than you think)

The Black Star Line was a financial failure, but a cultural triumph.

It proved that Black people could mobilize on a global scale. It showed that "ordinary" people were willing to invest in their own liberation.

Look at the flag of Ghana. When they gained independence in 1957, they put a black star right in the middle of their flag. Why? To honor Marcus Garvey. Their national soccer team is called the Black Stars.

Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of Ghana, openly admitted that Garvey’s philosophy was a huge influence on him. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X both cited Garvey as the man who first gave Black people a sense of dignity on a mass scale.

What You Can Learn From This

If you’re looking at this through a business lens, the takeaways are pretty clear.

Infrastructure matters. You can't just have a vision; you need the right engineers and the right lawyers. Garvey’s "buy it now, fix it later" approach killed his cash flow. He was "bleeding" money on repairs because he didn't do proper due diligence on the vessels.

Trust but verify. Garvey trusted people based on their shared goals, but many of his associates were either incompetent or working for the other side.

Symbolism has power. Even though the company went bankrupt, the idea of the Black Star Line survived for over a hundred years. Sometimes a "failure" in business is a "win" in history.

Your Next Steps

If you want to understand the modern push for economic independence, you have to look at the roots.

- Read the primary sources: Check out the Negro World archives if you can find them. It was the UNIA newspaper and gives you a raw look at what they were telling the public in 1920.

- Visit the sites: If you're in New York, go to Liberty Hall in Harlem. It’s not the original building, but the spirit of the movement is still there.

- Study the economics: Look into the "Negro Factories Corporation." Most people forget that Garvey also started laundries, grocery stores, and a publishing house.

Garvey's story is a reminder that the "safe" path doesn't usually change the world. He took a massive risk, and while he paid a heavy price for it, he changed the way millions of people viewed themselves.

🔗 Read more: George Burrill Net Worth: Why This Global Development Legend is Wealthier Than You Think

The ships might have sunk, but the star is still there.